causality

‘We know little about the effect of diet on health. That’s why so much is written about it’. That is the title of a post in which I advocate the view put by John Ioannidis that remarkably little is known about the health effects if individual nutrients. That ignorance has given rise to a vast industry selling advice that has little evidence to support it.

The 2016 Conference of the so-called "College of Medicine" had the title "Food, the Forgotten Medicine". This post gives some background information about some of the speakers at this event. I’m sorry it appears to be too ad hominem, but the only way to judge the meeting is via the track record of the speakers.

Quite a lot has been written here about the "College of Medicine". It is the direct successor of the Prince of Wales’ late, unlamented, Foundation for Integrated Health. But unlike the latter, its name is disguises its promotion of quackery. Originally it was going to be called the “College of Integrated Health”, but that wasn’t sufficently deceptive so the name was dropped.

For the history of the organisation, see

Don’t be deceived. The new “College of Medicine” is a fraud and delusion

The College of Medicine is in the pocket of Crapita Capita. Is Graeme Catto selling out?

The conference programme (download pdf) is a masterpiece of bait and switch. It is a mixture of very respectable people, and outright quacks. The former are invited to give legitimacy to the latter. The names may not be familiar to those who don’t follow the antics of the magic medicine community, so here is a bit of information about some of them.

The introduction to the meeting was by Michael Dixon and Catherine Zollman, both veterans of the Prince of Wales Foundation, and both devoted enthusiasts for magic medicne. Zollman even believes in the battiest of all forms of magic medicine, homeopathy (download pdf), for which she totally misrepresents the evidence. Zollman works now at the Penny Brohn centre in Bristol. She’s also linked to the "Portland Centre for integrative medicine" which is run by Elizabeth Thompson, another advocate of homeopathy. It came into being after NHS Bristol shut down the Bristol Homeopathic Hospital, on the very good grounds that it doesn’t work.

Now, like most magic medicine it is privatised. The Penny Brohn shop will sell you a wide range of expensive and useless "supplements". For example, Biocare Antioxidant capsules at £37 for 90. Biocare make several unjustified claims for their benefits. Among other unnecessary ingredients, they contain a very small amount of green tea. That’s a favourite of "health food addicts", and it was the subject of a recent paper that contains one of the daftest statistical solecisms I’ve ever encountered

"To protect against type II errors, no corrections were applied for multiple comparisons".

If you don’t understand that, try this paper.

The results are almost certainly false positives, despite the fact that it appeared in Lancet Neurology. It’s yet another example of broken peer review.

It’s been know for decades now that “antioxidant” is no more than a marketing term, There is no evidence of benefit and large doses can be harmful. This obviously doesn’t worry the College of Medicine.

Margaret Rayman was the next speaker. She’s a real nutritionist. Mixing the real with the crackpots is a standard bait and switch tactic.

Eleni Tsiompanou, came next. She runs yet another private "wellness" clinic, which makes all the usual exaggerated claims. She seems to have an obsession with Hippocrates (hint: medicine has moved on since then). Dr Eleni’s Joy Biscuits may or may not taste good, but their health-giving properties are make-believe.

Andrew Weil, from the University of Arizona

gave the keynote address. He’s described as "one of the world’s leading authorities on Nutrition and Health". That description alone is sufficient to show the fantasy land in which the College of Medicine exists. He’s a typical supplement salesman, presumably very rich. There is no excuse for not knowing about him. It was 1988 when Arnold Relman (who was editor of the New England Journal of Medicine) wrote A Trip to Stonesville: Some Notes on Andrew Weil, M.D..

“Like so many of the other gurus of alternative medicine, Weil is not bothered by logical contradictions in his argument, or encumbered by a need to search for objective evidence.”

This blog has mentioned his more recent activities, many times.

Alex Richardson, of Oxford Food and Behaviour Research (a charity, not part of the university) is an enthusiast for omega-3, a favourite of the supplement industry, She has published several papers that show little evidence of effectiveness. That looks entirely honest. On the other hand, their News section contains many links to the notorious supplement industry lobby site, Nutraingredients, one of the least reliable sources of information on the web (I get their newsletter, a constant source of hilarity and raised eyebrows). I find this worrying for someone who claims to be evidence-based. I’m told that her charity is funded largely by the supplement industry (though I can’t find any mention of that on the web site).

Stephen Devries was a new name to me. You can infer what he’s like from the fact that he has been endorsed byt Andrew Weil, and that his address is "Institute for Integrative Cardiology" ("Integrative" is the latest euphemism for quackery). Never trust any talk with a title that contains "The truth about". His was called "The scientific truth about fats and sugars," In a video, he claims that diet has been shown to reduce heart disease by 70%. which gives you a good idea of his ability to assess evidence. But the claim doubtless helps to sell his books.

Prof Tim Spector, of Kings College London, was next. As far as I know he’s a perfectly respectable scientist, albeit one with books to sell, But his talk is now online, and it was a bit like a born-again microbiome enthusiast. He seemed to be too impressed by the PREDIMED study, despite it’s statistical unsoundness, which was pointed out by Ioannidis. Little evidence was presented, though at least he was more sensible than the audience about the uselessness of multivitamin tablets.

Simon Mills talked on “Herbs and spices. Using Mother Nature’s pharmacy to maintain health and cure illness”. He’s a herbalist who has featured here many times. I can recommend especially his video about Hot and Cold herbs as a superb example of fantasy science.

Annie Anderson, is Professor of Public Health Nutrition and

Founder of the Scottish Cancer Prevention Network. She’s a respectable nutritionist and public health person, albeit with their customary disregard of problems of causality.

Patrick Holden is chair of the Sustainable Food Trust. He promotes "organic farming". Much though I dislike the cruelty of factory farms, the "organic" industry is largely a way of making food more expensive with no health benefits.

The Michael Pittilo 2016 Student Essay Prize was awarded after lunch. Pittilo has featured frequently on this blog as a result of his execrable promotion of quackery -see, in particular, A very bad report: gamma minus for the vice-chancellor.

Nutritional advice for patients with cancer. This discussion involved three people.

Professor Robert Thomas, Consultant Oncologist, Addenbrookes and Bedford Hospitals, Dr Clare Shaw, Consultant Dietitian, Royal Marsden Hospital and Dr Catherine Zollman, GP and Clinical Lead, Penny Brohn UK.

Robert Thomas came to my attention when I noticed that he, as a regular cancer consultant had spoken at a meeting of the quack charity, “YestoLife”. When I saw he was scheduled tp speak at another quack conference. After I’d written to him to point out the track records of some of the people at the meeting, he withdrew from one of them. See The exploitation of cancer patients is wicked. Carrot juice for lunch, then die destitute. The influence seems to have been temporary though. He continues to lend respectability to many dodgy meetings. He edits the Cancernet web site. This site lends credence to bizarre treatments like homeopathy and crystal healing. It used to sell hair mineral analysis, a well-known phony diagnostic method the main purpose of which is to sell you expensive “supplements”. They still sell the “Cancer Risk Nutritional Profile”. for £295.00, despite the fact that it provides no proven benefits.

Robert Thomas designed a food "supplement", Pomi-T: capsules that contain Pomegranate, Green tea, Broccoli and Curcumin. Oddly, he seems still to subscribe to the antioxidant myth. Even the supplement industry admits that that’s a lost cause, but that doesn’t stop its use in marketing. The one randomised trial of these pills for prostate cancer was inconclusive. Prostate Cancer UK says "We would not encourage any man with prostate cancer to start taking Pomi-T food supplements on the basis of this research". Nevertheless it’s promoted on Cancernet.co.uk and widely sold. The Pomi-T site boasts about the (inconclusive) trial, but says "Pomi-T® is not a medicinal product".

There was a cookery demonstration by Dale Pinnock "The medicinal chef" The programme does not tell us whether he made is signature dish "the Famous Flu Fighting Soup". Needless to say, there isn’t the slightest reason to believe that his soup has the slightest effect on flu.

In summary, the whole meeting was devoted to exaggerating vastly the effect of particular foods. It also acted as advertising for people with something to sell. Much of it was outright quackery, with a leavening of more respectable people, a standard part of the bait-and-switch methods used by all quacks in their attempts to make themselves sound respectable. I find it impossible to tell how much the participants actually believe what they say, and how much it’s a simple commercial drive.

The thing that really worries me is why someone like Phil Hammond supports this sort of thing by chairing their meetings (as he did for the "College of Medicine’s" direct predecessor, the Prince’s Foundation for Integrated Health. His defence of the NHS has made him something of a hero to me. He assured me that he’d asked people to stick to evidence. In that he clearly failed. I guess they must pay well.

Follow-up

This article has been re-posted on The Winnower, so it now has a digital object identifier: DOI: 10.15200/winn.142935.50603

The latest news: eating red meat doesn’t do any harm. But why isn’t that said clearly? Alarmism makes better news, not only for journalists but for authors and university PR people too.

I’ve already written twice about red meat.

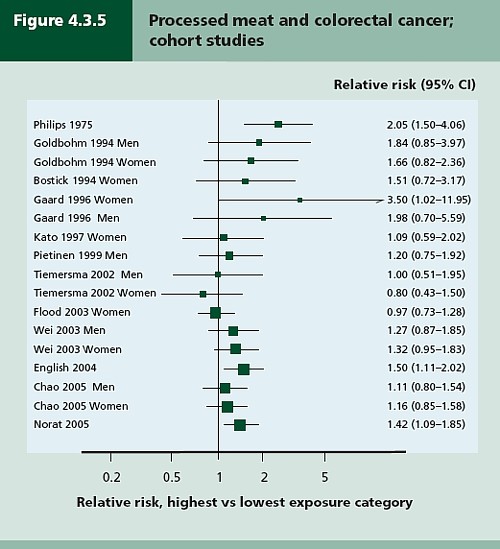

In May 2009 Diet and health. What can you believe: or does bacon kill you? based on the WCRF report (2007).

In March 2012 How big is the risk from eating red meat now? An update.

In the first of these I argued that the evidence produced by the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) for a causal relationship was very thin indeed. An update by WCRF in 2010 showed a slightly smaller risk, and weakened yet further the evidence for causality, though that wasn’t reflected in their press announcement.

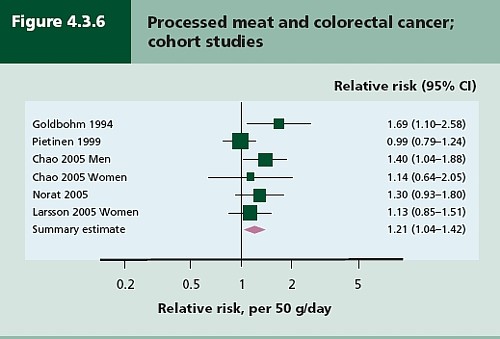

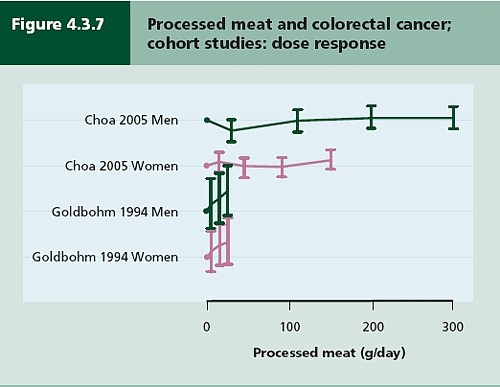

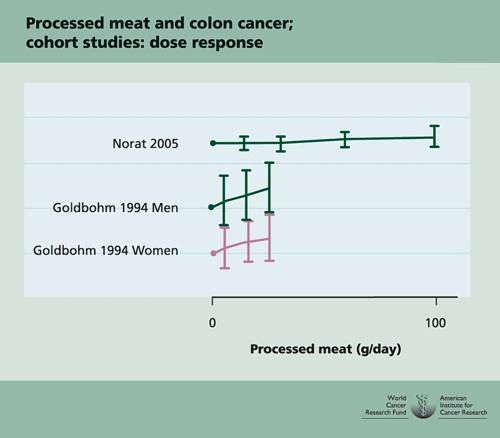

The 2012 update added observations from two very large cohort studies. The result was that the estimates of risk were less than half as big as in 2009. The relative risk of dying from colorectal cancer was 1.21 (95% Confidence interval 1.04–1.42) with 50 g of red or processed meat per day, whereas in the new study the relative risk for cancer was only 1.10 (1.06-1.14) for a larger ‘dose’, 85 g of red meat. Again this good news was ignored and dire warnings were issued.

This reduction in size of the effect as samples get bigger is exactly what’s expected for spurious correlations, as described by Ioannidis and others. And it seems to have come true. The estimate of the harm done by red meat has vanished entirely in the latest study.

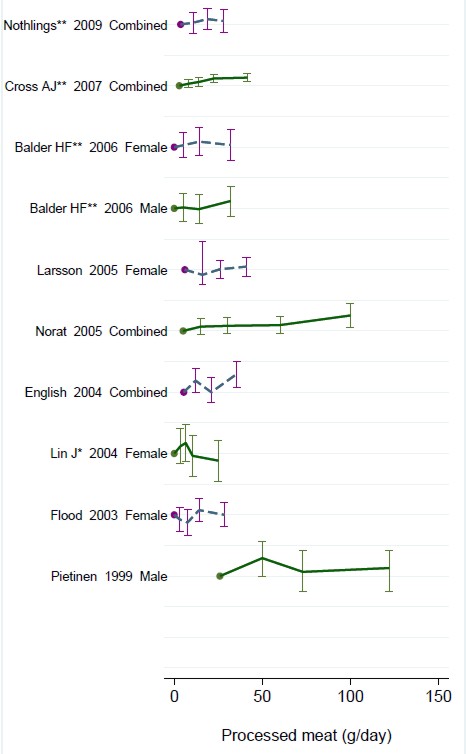

The EPIC study

This is the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition, another prospective cohort study, so it isn’t randomised [read the original paper]. And it was big, 448,568 people from ten different European countries. These people were followed for a median time of 12.7 years, and during follow-up 26,344 of them died.

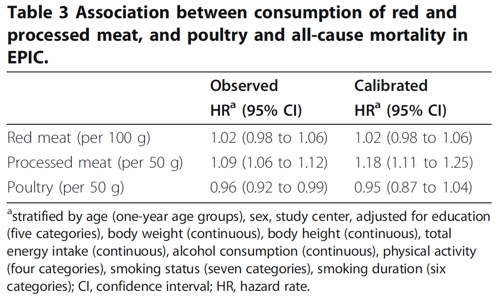

The thing that was different about this paper was that red meat was found to pose no detectable risk, as judged by all-cause mortality. But this wasn’t even mentioned in the headline conclusions.

Conclusions: The results of our analysis support a moderate positive association between processed meat consumption and mortality, in particular due to cardiovascular diseases, but also to cancer.

To find the result you have to dig into Table 3.

So, by both methods of calculation, the relative risk from eating red meat is negligible (except possibly in the top group, eating more than 160 g (7 oz) per day).

There is still an association between intake of processed meat and all-cause mortality, as in previous studies, though the association of processed meat with all-cause mortality, 1.09, or 1.18 depending on assumptions, is, if anything, smaller than was observed in the 2012 study, in which the relative risk was 1.20 (Table 2).

Assumptions, confounders and corrections.

The lowest meat eaters had only 13% of current smokers, but for the biggest red meat eaters it was 40%, for males. The alcohol consumption was 8.2 g/day for the lowest meat eaters but 23.4 g/day for the highest-meat group (the correlations were a bit smaller for women and also for processed meat eaters).

These two observations necessitate huge corrections to remove the (much bigger) effects of smoking and drinking if we want find the association for meat-eating alone. The main method for doing the correction is to fit the Cox proportional hazards model. This model assumes that there are straight-line relationships between the logarithm of the risk and the amount of each of the risk factors, e.g smoking, drinking, meat-eating and other risk factors. It may also include interactions that are designed to detect whether, for example, the effect of smoking on risk is or isn’t the same for people who drink different amounts.

Usually the straight-line assumption isn’t tested, and the results will depend on which risk factors (and which interactions between them) are included in the calculations. Different assumptions will give different answers. It simply isn’t known how accurate the corrections are when trying to eliminate the big effect of smoking in order to isolate the small effect of meat-eating. And that is before we get to other sorts of correction. For example, the relative risk from processed meat in Table 3, above, was 9% or 18% (1.09, or 1.18) depending on the outcome of a calculation that was intended to increase the accuracy of food intake records ("calibration").

The Conclusions of the new study don’t even mention the new result with red meat. All they mention is the risk from processed meat.

In this population, reduction of processed meat consumption to less than 20 g/day would prevent more than 3% of all deaths. As processed meat consumption is a modifiable risk factor, health promotion activities should include specific advice on lowering processed meat consumption.

Well, you would save that number of lives if, and only if, the processed meat was the cause of death. Too many epidemiologists, the authors pay lip service to the problem of causality in the introduction, but then go on to assume it in the conclusions. In fact the problem of causality isn’t even metnioned anywhere in either the 2012 study, or the new 2013 EPIC trial.

So is the risk of processed meat still real? Of course I can’t answer that. All that can be said is that it’s quite small, and as sample sizes get bigger, estimates of the risk are getting smaller. It wouldn’t be surprising if the risk from processed meat were eventually found not to exist, just as has happened for red (unprocessed) meat

The Japanese study

Last year there was another cohort study, with 51,683 Japanese. The results were even more (non-) dramatic [Nagao et al, 2012] than in the EPIC trial. This is how they summarise the results for the relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals).

"…for the highest versus lowest quintiles of meat consumption (77.6 versus 10.4 g/day) among men were 0.66 (0.45 — 0.97) for ischemic heart disease, 1.10 (0.84 — 1.43) for stroke and 1.00 (0.84 — 1.20) for total cardiovascular disease. The corresponding HRs (59.9 versus 7.5 g/day) among women were 1.22 (0.81 — 1.83), 0.91 (0.70 — 1.19) and 1.07 (0.90 — 1.28). The associations were similar when the consumptions of red meat, poultry, processed meat and liver were examined separately.

CONCLUSION: Moderate meat consumption, up to about 100 g/day, was not associated with increased mortality from ischemic heart disease, stroke or total cardiovascular disease among either gender."

In this study, the more meat (red or processed) you eat, the lower your risk of ischaemic heart disease (with the possible exception of overweight women). The risk of dying from any cardiovascular disease was unrelated to the amount of meat eaten (relative risk 1.0) whether processed meat or not.

Of course it’s possible that things which risky for Japanese people differ from those that are risky for Europeans. It’s also possible that even processed meat isn’t bad for you.

The carnitine study

The latest meat study to hit the headlines didn’t actually look at the effects of meat at all, though you wouldn’t guess that from the pictures of sausages in the headlines (not just in newspapers, but also in NHS Choices). The paper [reprint] was about carnitine, a substance that occurs particularly in beef, with lower amounts in pork and bacon, and in many other foods. The paper showed that bacteria in the gut can convert carnitine to a potentially toxic substance, trimethylamine oxide (TMAO). That harms blood vessels (at least in mice). But to show an effect in human subjects they were given an amount of carnitine equivalent to over 1 lb of steak, hardly normal, even in the USA.

The summary of the paper says it is an attempt to explain "the well-established link between high levels of red meat consumption and CVD [cardiovascular disease] risk". As we have just seen, it seems likely that this risk is far from being “well-established”. There is little or no such risk to explain.

It would be useful to have a diagnostic marker for heart disease, but this paper doesn’t show that carnitine or TMAO) is useful for that. It might also be noted that the authors have a maze of financial interests.

Competing financial interests Z.W. and B.S.L. are named as co-inventors on pending patents held by the Cleveland Clinic relating to cardiovascular diagnostics and have the right to receive royalty payments for inventions or discoveries related to cardiovascular diagnostics from Liposciences. W.H.W.T. received research grant support from Abbott Laboratories and served as a consultant for Medtronic and St. Jude Medical. S.L.H. and J.D.S. are named as co-inventors on pending and issued patents held by the Cleveland Clinic relating to cardiovascular diagnostics and therapeutics patents. S.L.H. has been paid as a consultant or speaker by the following companies: Cleveland Heart Lab., Esperion, Liposciences, Merck & Co. and Pfizer. He has received research funds from Abbott, Cleveland Heart Lab., Esperion and Liposciences and has the right to receive royalty payments for inventions or discoveries related to cardiovascular diagnostics from Abbott Laboratories, Cleveland Heart Lab., Frantz Biomarkers, Liposciences and Siemens.

The practical significance of this work was summed up the dietitian par excellence, Catherine Collins, on the BBC’s Inside Health programme.

Listen to Catherine Collins on carnitine.

She points out that the paper didn’t mean that we should change what we already think is a sensible diet.

At most, it suggests that it’s not a good idea to eat 1 lb steaks very day.

And the paper does suggest that it’s not sensible to take the carnitine supplements that are pushed by every gym. According to NIH

"twenty years of research finds no consistent evidence that carnitine supplements can improve exercise or physical performance in healthy subjects".

Carnitine supplements are a scam. And they could be dangerous.

Follow-up

Another blog on this topic, one from Cancer Research UK also fails to discuss the problem of causality. Neither does it go into the nature (and fallibility) of the corrections for counfounders like smoking and alcohol,. Nevertheless that, and an earlier post on Food and cancer: why media reports are often misleading, are a good deal more realistic than most newspaper reports.

This is a slightly-modified version of the article that appeared in BMJ blogs yesterday, but with more links to original sources, and a picture. There are already some comments in the BMJ.

The original article, diplomatically, did not link directly to UCL’s Grand Challenge of Human Wellbeing, a well-meaning initiative which, I suspect, will not prove to be value for money when it comes to practical action.

Neither, when referring to the bad effects of disempowerment on human wellbeing (as elucidated by, among others, UCL’s Michael Marmot), did I mention the several ways in which staff have been disempowered and rendered voiceless at UCL during the last five years. Although these actions have undoubtedly had a bad effect on the wellbeing of UCL’s staff, it seemed a litlle unfair to single out UCL since similar things are happening in most universities. Indeed the fact that it has been far worse at Imperial College (at least in medicine) has probably saved UCL from being denuded. One must be thankful for small mercies.

There is, i think, a lesson to be learned from the fact that formal initiatives in wellbeing are springing up at a time when university managers are set on taking actions that have exactly the opposite effect. A ‘change manager’ is not an adequate substitute for a vote. Who do they imagine is being fooled?

The A to Z of the wellbeing industry

From angelic reiki to patient-centred care

Nobody could possibly be against wellbeing. It would be like opposing motherhood and apple pie. There is a whole spectrum of activities under the wellbeing banner, from the undoubtedly well-meaning patient-centred care at one end, to downright barmy new-age claptrap at the other end. The only question that really matters is, how much of it works?

Let’s start at the fruitcake end of the spectrum.

One thing is obvious. Wellbeing is big business. And if it is no more than a branch of the multi-billion-dollar positive-thinking industry, save your money and get on with your life.

In June 2010, Northamptonshire NHS Foundation Trust sponsored a “Festival of Wellbeing” that included a complementary therapy taster day. In a BBC interview one practitioner used the advertising opportunity, paid for by the NHS, to say “I’m an angelic reiki master teacher and also an angel therapist.” “Angels are just flying spirits, 100 percent just pure light from heaven. They are all around us. Everybody has a guardian angel.” Another said “I am a member of the British Society of Dowsers and use a crystal pendulum to dowse in treatment sessions. Sessions may include a combination of meditation, colour breathing, crystals, colour scarves, and use of a light box.” You couldn’t make it up.

The enormous positive-thinking industry is no better. Barbara Ehrenreich’s book, Smile Or Die: How Positive Thinking Fooled America and the World, explains how dangerous the industry is, because, as much as guardian angels, it is based on myth and delusion. It simply doesn’t work (except for those who make fortunes by promoting it). She argues that it fosters the sort of delusion that gave us the financial crisis (and pessimistic bankers were fired for being right). Her interest in the industry started when she was diagnosed with cancer. She says

”When I was diagnosed, what I found was constant exhortations to be positive, to be cheerful, to even embrace the disease as if it were a gift. If that’s a gift, take me off your Christmas list,”

It is quite clear that positive thinking does nothing whatsoever to prolong your life (Schofield et al 2004; Coyne et al 2007; 2,3), any more than it will cure tuberculosis or cholera. “Encouraging patients to “be positive” only may add to the burden of having cancer while providing little benefit” (Schofield et al 2004). Far from being helpful, it can be rather cruel.

Just about every government department, the NHS, BIS, HEFCE, and NICE, has produced long reports on wellbeing and stress at work. It’s well known that income is correlated strongly with health (Marmot, M., 2004). For every tube stop you go east of Westminster you lose a year of life expectancy (London Health Observatory). It’s been proposed that what matters is inequality of income (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). The nature of the evidence doesn’t allow such a firm conclusion (Lynch et al. 2004), but that isn’t really the point. The real problem is that nobody has come up with good solutions. Sadly the recommendations at the ends of all these reports don’t amount to a hill of beans. Nobody knows what to do, partly because pilot studies are rarely randomised so causality is always dubious, and partly because the obvious steps are either managerially inconvenient, ideologically unacceptable, or too expensive.

Take two examples:

Sir Michael Marmot’s famous Whitehall study (Marmot, M., 2004) has shown that a major correlate of illness is lack of control over one’s own fate: disempowerment. What has been done about it?

In universities it has proved useful to managers to increase centralisation and to disempower academics, precisely the opposite of what Marmot recommends.

|

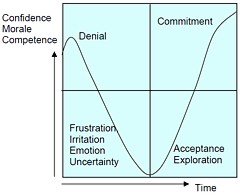

As long as it’s convenient to managers they are not going to change policy. Rather, they hand the job to the HR department which appoints highly paid “change managers,” who add to the stress by sending you stupid graphs that show you emerging from the slough of despond into eternal light once you realise that you really wanted to be disempowered after all. Or they send you on some silly “resilience” course. |

|

A second example comes from debt. According to a BIS report (Mental Capital and Wellbeing), debt is an even stronger risk factor for mental disorder than low income. So what is the government’s response to that? To treble tuition fees to ensure that almost all graduates will stay in debt for most of their lifetime. And this was done despite the fact that the £9k fees will save nothing for the taxpayer: in fact they’ll cost more than the £3k fees. The rise has happened, presumably, because the ideological reasons overrode the government’s own ideas on how to make people happy.

Nothing illustrates better the futility of the wellbeing industry than the response that is reported to have been given to a reporter who posed as an applicant for a “health, safety, and wellbeing adviser” with a local council. When he asked what “wellbeing” advice would involve, a member of the council’s human resources team said: “We are not really sure yet as we have only just added that to the role. We’ll want someone to make sure that staff take breaks, go for walks — that kind of stuff.”

The latest wellbeing notion to re-emerge is the happiness survey. Jeremy Bentham advocated “the greatest happiness for the greatest number,” but neglected to say how you measure it. A YouGov poll asks, “what about your general well-being right now, on a scale from 1 to 10.” I have not the slightest idea about how to answer such a question. As always some things are good, some are bad, and anyway wellbeing relative to whom? Writing this is fun. Trying to solve an algebraic problem is fun. Constant battling with university management in order to be able to do these things is not fun. The whole exercise smacks of the sort of intellectual arrogance that led psychologists in the 1930s to claim that they could sum up a person’s intelligence in a single number. That claim was wrong and it did great social harm.

HEFCE has spent a large amount of money setting up “pilot studies” of wellbeing in nine universities. Only one is randomised, so there will be no evidence for causality. The design of the pilots is contracted to a private company, Robertson Cooper, which declines to give full details but it seems likely that the results will be about as useless as the notorious Durham fish oil “trials”(Goldacre, 2008).

Lastly we get to the sensible end of the spectrum: patient-centred care. Again this has turned into an industry with endless meetings and reports and very few conclusions. Epstein & Street (2011) say

“Helping patients to be more active in consultations changes centuries of physician-dominated dialogues to those that engage patients as active participants. Training physicians to be more mindful, informative, and empathic transforms their role from one characterized by authority to one that has the goals of partnership, solidarity, empathy, and collaboration.”

That’s fine, but the question that is constantly avoided is what happens when a patient with metastatic breast cancer expresses a strong preference for Vitamin C or Gerson therapy, as advocated by the YesToLife charity. The fact of the matter is that the relationship can’t be equal when one party, usually (but not invariably) the doctor, knows a lot more about the problem than the other.

What really matters above all to patients is getting better. Anyone in their right mind would prefer a grumpy condescending doctor who correctly diagnoses their tumour, to an empathetic doctor who misses it. It’s fine for medical students to learn social skills but there is a real danger of so much time being spent on it that they can no longer make a correct diagnosis. Put another way, there is confusion between caring and curing. It is curing that matters most to patients. It is this confusion that forms the basis of the bait and switch tactics (see also here) used by magic medicine advocates to gain the respectability that they crave but rarely deserve.

If, as is only too often the case, the patient can’t be cured, then certainly they should be cared for. That’s a moral obligation when medicine fails in its primary aim. There is a lot of talk about individualised care. It is a buzzword of quacks and also of the libertarian wing which says NICE is too prescriptive. It sounds great, but it helps only if the individualised treatment actually works.

Nobody knows how often medicine fails to be “patient-centred.”. Even less does anyone know whether patient-centred care can improve the actual health of patients. There is a strong tendency to do small pilot trials that are as likely to mislead as inform. One properly randomised trial (Kinmonth et al., 1998) concluded

“those committed to achieving the benefits of patient centred consulting should not lose the focus on disease management.”

Non-randomised studies may produce more optimistic conclusions (e.g. Hojat et al, 2011), but there is no way to tell if this is simply because doctors find it easy to be empathetic with patients who have better outcomes.

Obviously I’m in favour of doctors being nice to patients and to listening to their wishes. But there is a real danger that it will be seen as more important than curing. There is also a real danger that it will open the doors to all sorts of quacks who claim to provide individualised empathic treatment, but end up recommending Gerson therapy for metastatic breast cancer. The new College of Medicine, which in reality is simply a reincarnation of the late unlamented Prince’s Foundation for Integrated Health, lists as its founder Capita, the private healthcare provider that will, no doubt, be happy to back the herbalists and homeopaths in the College of Medicine, and, no doubt, to make a profit from selling their wares to the NHS.

In my own experience as a patient, there is not nearly as much of a problem with patient centred care as the industry makes out. Others have been less lucky, as shown by the mid-Staffordshire disaster (Delamothe, 2010), That seems to have resulted from PR being given priority over patients. Perhaps all that’s needed is to save money on all the endless reports and meetings (“the best substitute for work”), ban use of PR agencies (paid lying) and to spend the money on more doctors and nurses so they can give time to people who need it. This is a job that will be hindered considerably by the government’s proposals to sell off NHS work to private providers who will be happy to make money from junk medicine.

Reference

Wilkinson. R & Pickett, K. 2009 , The Spirit Level, ISBN 978 1 84614 039 6

A footnote on Robertson Cooper and "resilience"

I took up the offer of Robertson Cooper to do their free "resilience" assessment, the company to which HEFCE has paid an undisclosed amount of money.

The first problem arose when it asked about your job. There was no option for scientist, mathematician, university or research, so I was forced to choose "education and training". (a funny juxtaposition since training is arguably the antithesis of education). It had 195 questions. mostly as unanswerable as in the YouGov happiness survey. I particularly liked question 124 "I see little point in many of the theoretical models I come across". The theoretical models that I come across most are Markov models for the intramolecular changes in a receptor molecule when it binds a ligand (try, for example, Joint distributions of apparent open and shut times of single-ion channels and maximum likelihood fitting of mechanisms). I doubt the person who wrote the question has ever heard of a model of that sort. The answer to that question (and most of the others) would not be worth the paper they are written on.

The whole exercise struck me as the worst sort of vacuous HR psychobabble. It is worrying that HEFCE thinks it is worth spending money on it.

Follow-up

This post recounts a complicated story that started in January 2009, but has recently come to what looks like a happy ending. The story involves over a year’s writing of letters and meetings, but for those not interested in the details, I’ll start with a synopsis.

Synopsis of the synopsis

In January 2009, a course in "integrated medicine" was announced that, it was said, would be accredited by the University of Buckingham. The course was to be led by Drs Rosy Daniel and Mark Atkinson. So I sent an assessment of Rosy Daniel’s claims to "heal" cancer to Buckingham’s VC (president), Terence Kealey, After meeting Karol Sikora and Rosy Daniel, I sent an analysis of the course tutors to Kealey who promptly demoted Daniel, and put Prof Andrew Miles in charge of the course. The course went ahead in September 2009. Despite Miles’ efforts, the content was found to be altogether too alternative. The University of Buckingham has now terminated its contract with the "Faculty of Integrated Medicine", and the course will close. Well done.Buckingham.

Synopsis

- January 2009. I saw an announcement of a Diploma in Integrated Medicine, to be accredited by the University of Buckingham (UB). The course was to be run by Drs Rosy Daniel and Mark Atkinson of the College of Integrated Medicine, under the nominal directorship of Karol Sikora (UB’s Dean of Medicine). I wrote to Buckingham’s vice-chancellor (president), Terence Kealey, and attached a reprint of Ernst’s paper on carctol, a herbal cancer ‘remedy’ favoured by Daniiel.

- Unlike most vice-chancellors, Kealey replied at once and asked me to meet Sikora and Daniel. I met first Sikora alone, and then, on March 19 2009, both together. Rosy Daniel gave me a complete list of the speakers she’d chosen. Most were well-known alternative people, some, in my view, the worst sort of quack. After discovering who was to teach on the proposed course, I wrote a long document about the proposed speakers and sent it to the vice-chancellor of the University of Buckingham, Terence Kealey on March 23rd 2009.. Unlike most VCs, he took it seriously. At the end of this meeting I asked Sikora, who was in nominal charge of the course, how many of the proposed tutors he’d heard of. The answer was "none of them"

- Shortly before this meeting, I submitted a complaint to Trading Standards about Rosy Daniel’s commercial site, HealthCreation, for what seemed to me to be breaches of the Cancer Act 1939, by claims made for Carctol. Read the complaint.

- On 27th April 2009, I heard from Kealey that he’d demoted Rosy Daniel from being in charge of the Diploma and appointed Andrew Miles, who had recently been appointed as Buckingham’s Professor of Public Health Education and Policy &Associate Dean of Medicine (Public Health). Terence Kealey said "You’ve done us a good turn, and I’m grateful". Much appreciated. Miles said the course “needs in my view a fundamental reform of content. . . “

- Although Rosy Daniel had been demoted, she was still in charge of delivering the course at what had, by this time, changed its name to the Faculty of Integrated Medicine which, despite its name, is not part of the university.

- Throughout the summer I met Miles (of whom more below) several times and exchanged countless emails, but still didn’t get the revised list of speakers. The course went ahead on 30 September 2009. He also talked with Michael Baum and Edzard Ernst.

- By January 2010, Miles came to accept that the course was too high on quackery to be a credit to the university, and simply fired The Faculty of Integrated Medicine. Their contract was not renewed. Inspection of the speakers, even after revision of the course, shows why.

- As a consequence, it is rumoured that Daniel is trying to sell the course to someone else. The University of Middlesex, and unbelievably, the University of Bristol, have been mentioned, as well as Thames Valley University, the University of Westminster, the University of Southampton and the University of East London. Will the VCs of these institutions not learn something from Buckingham’s experience? It is to be hoped that they would at the very least approach Buckingham to ask pertinent questions? But perhaps a more likely contender for an organisation with sufficient gullibility is the Prince of Wales newly announced College of Integrated Medicine. [but see stop press]

The details of the story

The University of Buckingham (UB) is the only private university in the UK. Recently it announced its intention to start a school of medicine (the undergraduate component is due to start in September 2011). The dean of the new school is Karol Sikora.

Karol Sikora shot to fame after he appeared in a commercial in the USA. The TV commercial was sponsored by a far-right Republican campaign group, “Conservatives for Patients’ Rights” It designed to prevent the election of Barack Obama, by pouring scorn on the National Health Serrvice. A very curious performance. Very curious indeed. And then there was a bit of disagreement about the titles that he claimed to have.

As well as being dean of medicine at UB. Karol Sikora is also medical research director of CancerPartnersUK. a private cancer treatment company. He must be a very busy man.

Karol Sikora’s attitude to quackery is a mystery wrapped in an enigma. As well as being a regular oncologist, he is also a Foundation Fellow of that well known source of unreliable information, The Prince of Wales Foundation for Integrated Health. He spoke at their 2009 conference.

In the light of that, perhaps it is not, after all, so surprising thet the first action of UB’s medical school was to accredit a course a Diploma in Integrated Medicine. This course has been through two incarnations. The first prospectus (created 21 January 2009) advertised the course as being run by the British College of Integrated Medicine.But by the time that UB issued a press release in July 2009, the accredited outfit had changed its name to the Faculty of Integrated Medicine That grand title makes it sound like part of a university. It isn’t.

Rosy Daniel runs a company, Health Creation which, among other things, recommended a herbal concoction. Carctol. to "heal" cancer, . I wrote to Buckingham’s vice-chancellor (president), Terence Kealey, and attached a reprint of Ernst’s paper on Carctol. . Unlike most university vice-chancellors, he took it seriously. He asked me to meet Karol Sikora and Rosy Daniel to discuss it. After discovering who was teaching on this course, I wrote a document about their backgrounds and sent it to Terence Kealey. The outcome was that he removed Rosy Daniel as course director and appointed in her place Andrew Miles, with a brief to reorganise the course. A new prospectus, dated 4 September 2009, appeared. The course is not changed as much as I’d have hoped, although Miles assures me that while the lecture titles themselves may not have changed, he had ordered fundamental revisions to the teaching content and the teaching emphases.

In the new prospectus the British College of Integrated Medicine has been renamed as the Faculty of Integrated Medicine, but it appears to be otherwise unchanged. That’s a smart bit of PR. The word : “Faculty” makes it sound as though the college is part of a university. It isn’t. The "Faculty" occupies some space in the Apthorp Centre in Bath, which houses, among other things, Chiropract, Craniopathy (!) and a holistic vet,

The prospectus now starts thus.

The Advisory Board consists largely of well-know advocates of alternative medicine (more information about them below).

Most of these advisory board members are the usual promoters of magic medicine. But three of them seem quite surprising,Stafford Lightman, Nigel Sparrow and Nigel Mathers.

Stafford Lightman? Well actually I mentioned to him in April that his name was there and he asked for it to be removed, on the grounds that he’d had nothing to do with the course. It wasn’t removed for quite a while, but the current advisory board has none of these people. Nigel Sparrow and Nigel Mathers, as well as Lightman, sent letters of formal complaint to Miles and Terence Kealey, the VC of Buckingham, to complain that their involvement in Rosy Daniel’s set-up had been fundamentally misrepresented by Daniel. With these good scientists having extricated themselves from Daniel’s organisation, the FIM has only people who are firmly in the alternative camp (or quackery, as i’d prefer to call it). For example, people like Andrew Weil and George Lewith.

Andrew Weil, for example, while giving his address as the University of Arizona, is primarily a supplement salesman. He was recently reprimanded by the US Food and Drugs Administration

“Advertising on the site, the agencies said in the Oct. 15 letter, says “Dr. Weil’s Immune Support Formula can help maintain a strong defense against the flu” and claims it has “demonstrated both antiviral and immune-boosting effects in scientific investigation.”

The claims are not true, the letter said, noting the “product has not been approved, cleared, or otherwise authorized by FDA for use in the diagnosis, mitigation, prevention, treatment, or cure of the H1N1 flu virus.”

This isn’t the first time I’ve come across people’s names being used to support alternative medicine without the consent of the alleged supporter. There was, for example, the strange case of Dr John Marks and Patrick Holford.

Misrepresentation of this nature seems to be the order of the day. Could it be that people like Rosy Daniel are so insecure or, indeed, so unimportant within the Academy in real terms (where is there evidence of her objective scholarly or clinical stature?), that they seek to attach themselves, rather like limpets to fishing boats, to people of real stature and reputation, in order to boost their own or others’ view of themselves by a manner of proxy?

The background

When the course was originally proposed, a brochure appeared. It said accreditation by the University of Buckingham was expected soon.

Not much detail appeared in the brochure, Fine words are easy to write but what matters is who is doing th teaching. So I wrote to the vice-chancellor of Buckingham, Terence Kealey. I attached a reprint of Ernst’s paper on carctol, a herbal cancer ‘remedy’ favoured by Daniel (download the cached version of her claims, now deleted).

Terence Kealey

Kealey is regarded in much of academia as a far-right maverick, because he advocates ideas such as science research should get no public funding,and that universities should charge full whack for student fees. He has, in fact, publicly welcomed the horrific cuts being imposed on the Academy by Lord Mandelson. His piece in The Times started

“Wonderful news. The Government yesterday cut half a billion pounds from the money it gives to universities”

though the first comment on it starts

"Considerable accomplishment: to pack all these logical fallacies and bad metaphors in only 400 words"

He and I are probably at opposite ends of the political spectrum. Yet he is the only VC who has been willing to talk about questions like this. Normally letters to vice-chancellors about junk degrees go unanswered. Not so with Kealey. I may disagree with a lot of his ideas, but he is certainly someone you can do business with.

Kealey responded quickly to my letter, sent in January 2009, pointing out that Rosy Daniel’s claims about Carctol could not be supported and were possibly illegal. He asked me to meet Sikora and Daniel. I met first Sikora alone, and then, on March 19 2009, both together. Rosy Daniel gave me a complete list of the speakers she’d chosen to teach on this new Diploma on IM.

After discovering who was to teach on the proposed course, I wrote a long document about the proposed speakers and sent it to Terence Kealey on March 23rd 2009. It contained many names that will be familiar to anyone who has taken an interest in crackpot medicine, combined with a surprisingly large element of vested financial interests. Unlike most VCs, Kealey took it seriously.

The remarkable thing about this meeting was that I asked Sikora how many names where familiar to him on the list of people who had been chosen by Rosy Daniel to teach on the course. His answer was "none of them". Since his name and picture feature in all the course descriptions, this seemed like dereliction of duty to me.

After seeing my analysis of the speakers, Terence Kealey reacted with admirable speed. He withdrew the original brochure, demoted Rosy Daniel (in principle anyway) and brought in Prof Andrew Miles to take responsibility for the course. This meant that he had to investigate the multiple conflicts of interests of the various speakers and to establish some sort of way forward in the ‘mess’ of what had been agreed before Miles’ appointment to Buckingham

Andrew Miles.

Miles is an interesting character, a postdoctoral neuroendocrinologist, turned public health scientist. I’d come across him before as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice This is a curious journal that is devoted mainly to condemning Evidence Based Medicine. Much of its content seems to be in a style that I can only describe as post-modernist-influenced libertarian.

The argument turns on what you mean by ‘evidence’ and, in my opinion, Miles underestimates greatly the crucial problem of causality, a problem that can be solved only by randomisation, His recent views on the topic can be read here.

An article in Miles’ journal gives its flavour: "Andrew Miles, Michael Loughlin and Andreas Polychronis, Medicine and evidence: knowledge and action in clinical practice". Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2007, 13, 481–503 [download pdf]. This paper launches an attack on Ben Goldacre, in the following passage.

“Loughlin identifies Goldacre [36] as a particularly luminous example of a commentator who is able not only to combine audacity with outrage, but who in a very real way succeeds in manufacturing a sense of having been personally offended by the article in question. Such moralistic posturing acts as a defence mechanism to protect cherished assumptions from rational scrutiny and indeed to enable adherents to appropriate the ‘moral high ground’, as well as the language of ‘reason’ and ‘science’ as the exclusive property of their own favoured approaches. Loughlin brings out the Orwellian nature of this manoeuvre and identifies a significant implication.”

"If Goldacre and others really are engaged in posturing then their primary offence, at least according to the Sartrean perspective adopted by Murray et al. is not primarily intellectual, but rather it is moral. Far from there being a moral requirement to ‘bend a knee’ at the EBM altar, to do so is to violate one’s primary duty as an autonomous being.”

This attack on one of my heroes was occasioned because he featured one of the most absurd pieces of post-modernist bollocks ever, in his Guardian column in 2006. I had a go at the same paper on this blog, as well as an earlier one by Christine Barry, along the same lines. There was some hilarious follow-up on badscience.net. After this, it is understandable that I had not conceived a high opinion of Andrew Miles. I feared that Kealey might have been jumping out of the frying pan into the fire.

After closer acquaintance I have changed my mind, In the present saga Andrew Miles has done an excellent job. He started of sending me links to heaven knows how many papers on medical epistemology, to Papal Encyclicals on the proposed relationship between Faith and Reason and on more than one occasion articles from the Catholic Herald (yes, I did read it). This is not entirely surprising, as Miles is a Catholic priest as well as a public health academic, so has two axes to grind. But after six months of talking, he now sends me links to junk science sites of the sort that I might get from, ahem, Ben Goldacre.

Teachers on the course

Despite Andrew Miles best efforts, he came in too late to prevent much of the teaching being done in the parallel universe of alternative medicine, The University of Buckingham had a pre-Miles, legally-binding contract (now terminated) with the Faculty of Integrated Medicine, and the latter is run by Dr Rosy Daniel and Dr Mark Atkinson. Let’s take a look at their record.

Rosy Daniel BSc, MBBCh

Dr Rosy Daniel first came to my attention through her commercial web site, Health Creation. This site, among other things, promoted an untested herbal concoction, Carctol, for "healing" cancer.

Carctol: Profit before Patients? is a review by Edzard Ernst of the literature, such as it is, and concludes

Carctol and the media hype surrounding it must have given many cancer patients hope. The question is whether this is a good or a bad thing. On the one hand, all good clinicians should inspire their patients with hope [6]. On the other hand, giving hope on false pretences is cruel and unethical. Rosy Daniel rightly points out that all science begins with observations [5]. But all science then swiftly moves on and tests hypotheses. In the case of Carctol, over 20 years of experience in India and almost one decade of experience in the UK should be ample time to do this. Yet, we still have no data. Even the small number of apparently spectacular cases observed by Dr. Daniel have not been published in the medical literature.

On this basis I referred Health Creation to Trading Standards officer for a prima facie breach of the Cancer Act 1939. ]Download the complaint document]. Although no prosecution was brought by Trading Standards, they did request changes in the claims that were being made. Here is an example.

A Google search of the Health Creation site for “Carctol” gives a link

Dr Daniel has prescribed Carctol for years and now feels she is seeing a breakthrough. Dr Daniel now wants scientists to research the new herbal medicine

But going to the link produces

Access denied.

You are not authorized to access this page.

You can download the cached version of this page, which shows the sort of claims that were being made before Trading Standards Officers stepped in. There are now only a few oblique references to Carctol on the Health Creation site, e.g. here..

Both Rosy Daniel and Karol Sikora were speakers at the 2009 Princes’s Foundation Conference, in some odd company.

Mark Atkinson MBBS BSc (Hons) FRIPH

Dr Mark Atkinson is co-leader of the FiM course. He is also a supplement salesman, and he has promoted the Q-link pendant. The Q-link pendant is a simple and obvious fraud designed to exploit paranoia about WiFi killing you. When Ben Goldacre bought one and opened it. He found

“No microchip. A coil connected to nothing. And a zero-ohm resistor, which costs half a penny, and is connected to nothing.”

Nevertheless, Mark Atkinson has waxed lyrical about this component-free device.

“As someone who used to get tired sitting in front of computers and used to worry about the detrimental effects of external EMF’s, particularly as an avid user of mobile phones, I decided to research the various devices and technologies on the market that claim to strengthen the body’s subtle energy fields. It was Q Link that came out top. As a Q link wearer, I no longer get tired whilst at my computer, plus I’m enjoying noticeably higher energy levels and improved mental performance as a result of wearing my Q Link. I highly recommend it.” Dr Mark Atkinson, Holistic Medical Physician

Mark Atkinson is also a fan of Emo-trance. He wrote, In Now Magazine,

"I wanted you to know that of all the therapies I’ve trained in and approaches that I have used (and there’s been a lot) none have excited me and touched me so deeply than Emotrance."

"Silvia Hartmann’s technique is based on focusing your thoughts on parts of your body and guiding energy. It can be used for everything from insomnia to stress. The good news is that EmoTrance shows you how to free yourself from these stuck emotions and release the considerable amounts of energy that are lost to them."

Aha so this particular form of psychobabble is the invention of Silvia Hartmann. Silvia Hartmann came to my attention because her works feature heavily in on of the University of Westminster’s barmier “BSc” degrees, in ‘naturopaths’, described here. She is fanous, apart from Emo-trance, for her book Magic, Spells and Potions

“Dr Hartmann has created techniques that will finally make magic work for you in ways you never believed to be possible.”

Times Higher Education printed a piece with the title ‘Energy therapy’ project in school denounced as ‘psychobabble’. They’d phoned me a couple of days earlier to see whether I had an opinion about “Emotrance”. As it happens, I knew a bit about it because it had cropped up in a course given at, guess where, the University of Westminster . It seems that a secondary school had bought this extreme form of psychobabble. The comments on the Times Higher piece were unusually long and interesting.

It turned out that the inventor of “Emotrance”, Dr Silvia Hartmann PhD., not only wrote books about magic spells and potions, but also that her much vaunted doctorate had been bought from the Universal Life Church, current cost $29.99.

The rest of the teachers

The rest of the teachers on the course, despite valiant attempts at vetting by Andrew Miles, includes many names only too well-known to anybody who has taken and interest in pseudo-scientific medicine. Here are some of them.

Damien Downing:, even the Daily Mail sees through him. Enough said.

Kim Jobst, homoepath and endorser of the obviously fraudulent Q-link

pendant. His Plaxo profile says

About Kim A. Jobst

Consultant, Wholystic Care Physician [sic!] , Medical Homoeopath, Specialist in Neurodegeneration and Dementia, using food state nutrition, diet and lifestyle to facilitate Healing and Growth;

Catherine Zollman, Well known ally of HRH and purveyer of woo.

Harald Walach, another homeopath, fond of talking nonsense about "quantum effects".

Nicola Hembry, a make-believe nutritionist and advocate of vitamin C and laetrile for cancer

Simon Mills, a herbalist who is inclined to diagnoses like “hot damp”, ro be treated with herbs that tend to “cool and dry.”

David Peters, of the University of Westminster. Enough said.

Nicola Robinson of Thames Valley University. Advocate of unevidenced treatmsnts.

Michael Dixon, of whom more here.

And last but not least,

Karol Sikora.

The University of Buckingham removes accreditation of the Faculty of Integrated Medicine

The correspondence has been long and, at times, quite blunt. Here are a few quotations from it, The University of Buckingham, being private, is exempt from the Freedom of Information Act (2000) but nevertheless they have allowed me to reproduce the whole of the correspondence. The University, through its VC, Terence Keeley, has been far more open than places that are in principle subject to FOIA, but which, in practice, always try to conceal material. I may post the lot, as time permits, but meanwhile here are some extracts. They make uncomfortable reading for advocates of magic medicine.

Miles to Daniel, 8 Dec 2009

” . . . now that the University has taken his [Sikora’s] initial advice in trialing the DipSIM and has found it cost-ineffective, the way forward is therefore to alter that equation through more realistic financial contribution from IHT/FIM at Bath or to view the DipSIM as an experiment that has failed and which must give way to other more viable initiatives."

"The University is also able to confirm that we hold no interest in jointly developing any higher degrees on the study of IM with IHT/FIM at Bath. This is primarily because we are developing our own Master’s degree in Medicine of the Person in collaboration with various leading international societies and scholars including the WHO and which is based on a different school of thought. "

Miles to Daniel 15 Dec 2009

"Dear Rosy

It appears that you have not fully assimilated the content of my earlier e-mails and so I will reiterate the points I have already made to you and add to them.

The DipSIM is an external activity – in fact, it is an external collaboration and nothing more. It is not an internal activity and neither is it in any way part of the medical school and neither will it become so and so the ‘normal rules’ of academic engagement and scholarly interchange do not apply. Your status is one of external collaborator and not one of internal or even visiting academic colleague. There is no “joint pursuit” of an academically rigorous study of IM by UB and IHT/FIM beyond the DipSIM and there are no plans, and never have been, for the “joint definition of research priorities” in IM. The DipSIM has been instituted on a trial basis and this has so far shown the DipSIM to be profoundly cost-ineffective for the University. You appear to misunderstand this – deliberately or otherwise."

Daniel to Miles 13 Jan 2010

"However, I am aware that weather permitting you and Karol will be off to the Fellows meeting for the newly forming National College (for which role I nominated you to Dr Michael Dixon and Prof David Peters.)

I have been in dialogue with Michael and Boo Armstrong from FIH and they are strongly in favour of forming a partnership with FIM so that we effectively become one of many new faculties within the College (which is why we change our name to FIM some months ago).

I have told Michael about the difficulties we are having and he sincerely hopes that we can resolve them so that we can all move forward as one. "

Miles to Daniel 20 Jan 2010

"Congratulations on the likely integration of your organisation into the new College of Integrative Health which will develop out of the Prince’s Foundation for Integrated Health. This

will make an entirely appropriate home for you for the longer term.Your image of David Colquhoun "alive and kicking" as the Inquisitor General, radiating old persecutory energy and believing "priestess healers" (such as you describe youself) to be best "tortured, drowned and even burnt alive", will remain with me, I suspect, for many years to come (!). But then, as the Inquisitor General did say, ‘better to burn in this life than in the next’ (!). Overall, then, I reject your conclusion on the nature of the basis of my decision making and playfully suggest that it might form part of the next edition of Frankfurt’s recent volume ["On Bullshit] http://press.princeton.edu/titles/7929.html I hope you will forgive my injection of a little academic humour in an otherwise formal and entirely serious communication.

The nature of IM, with its foundational philosophy so vigorously opposed by mainstream medicine and the conitnuing national and international controversies which engulf homeopaths, acupuncturists, herbalists, naturopaths, transcendental meditators, therapeutic touchers, massagers, reflexologists, chiropractors, hypnotists, crystal users, yoga practitioners, aromatherapists, energy channelers, chinese medicine practitioners et al, can only bring the University difficulties as we seek to establish a formal and internationally recognised School of Medicine and School of Nursing.

I do not believe my comments in relation to governance at Bath are "offensive". They are, on the contrary, entirely accurate and of concern to the University. There have been resignations at senior level from your Board due to misrepresentation of your position and there has been a Trading Standards Authority investigation into further instances of misrepresentation. I am advised that an audit is underway of your compliance with the Authority’s instructions. You have therefore not dealt with my concerns, you have merely described them as "offensive".

I note from your e-mail that you are now in discussions with other universities and given the specific concerns of the University of Buckingham which I have dealt with exhaustively in this and other correspondences and the incompatibility of the developments at UB with the DipSIM and your own personal ambitions, etc., I believe you to have taken a very wise course and I wish you well in your negotiations. In these circumstances I feel it appropriate to enhance those negotiations by confirming that the University of Buckingham will not authorise the intake of a second cohort of students and that the relationship between IHT and the University will cease following the graduation of those members of the current course that are successful in their studies – the end of February 2011."

From Miles 2 Feb 2010

"Here is the list of teachers – you can subtract me (I withdrew from teaching when the antics ay Bath started) and also Professor John Cox (Former President of The Royal College of Psychiatrists and Former Secretary General of the World Psychiatric Association) who withdrew when he learned of some of the stuff going on…. Karol Sikora continues to teach. Michael Loughlin and Carmel Martin are both good colleagues of mine and, I can assure you – taught the students solid stuff! Michael taught medical epistemology and Carmel the emerging field of systems complexity in health services (Both of them have now withdrawn from teaching commitments).

The tutors shown are described by Rosy as the finest minds in IM teaching in the country. I interviewed tham all personally on (a) the basis of an updated CV & (b) via a 30 min telephone interview with me personally. Some were excluded from teaching because they were not qualified to do so academically (e.g. Boo Armstrong, Richard Falmer, not even a first degree, etc, etc., but gave a short presentation in a session presided over by an approved teacher) and others were approved because of their academic qualifications, PhD, MD, FRCP etc etc etc) and activity within the IM field. Each approved teacher was issued with highly specific teaching guidance form me (no bias, reference to opposing schools of thought, etc etc) and each teacher was required to complete and sign a Conflicts of Interest form. All of these documentations are with me here. Short of all this governance it’s impossible to bar them from teaching because who else would then do it?! Anyway, the end is in sight – Hallelujah! "

From Miles 19 Feb 2010

"Dear David

Just got back to the office after an excellent planning meeting for the new Master’s Degree in Person-centred Medicine and a hearty (+ alcoholic) lunch at the Ath! Since I shall never be a FRS, the Ath seems to me the next best ‘club’ (!). Michael Baum is part of the steering committee and you might like to take his thoughts on the direction of the programme. Our plans may even find their way into your Blog as an example of how to do things (vs how not to do things, i.e. CAM, IM, etc!). This new degree will sit well alongside the new degrees in Public Health – i.e. the population/utilitarian outlook of PH versus the individual person-centred approach., etc. "

And an email from a senior UB spokesperson

"Rumour has it that now that Buckingham has dismissed the ‘priestess healer of Bath’, RD [Rosy Daniel] , explorations are taking place with other universities, most of which are subject to FoI request from DC at the time of writing. Will these institutions have to make the same mistakes Buckingham did before taking the same action? Rumour also has it that RD changed the name of her institution to FIM in order to fit neatly into the Prince’s FIH, a way, no doubt, of achieving ‘protection’ and ‘accreditation’ in parallel with particularly lucrative IM ‘education’ (At £9,000 a student and with RD’s initial course attracting 20 mainly GPs, that’s £180,00 – not bad business…. And Buckingham’s ‘share of this? £12,000!”

The final bombshell; even the Prince of Wales’ FIH rejects Daniel and Atkinson?

Only today (31 March) I was sent, from a source that I can’t reveal, an email which comes from someone who "represent the College and FIH . . . ".. This makes it clear that the letter comes from the Prince of Wales’ Foundation for Integrated Health

|

Dr Rosy Daniel BSc MBBCh Director of the Faculty of Integrated Medicine Medical Director Health Creation 30th March 2010 RE: Your discussion paper and recent correspondence Thank you for meeting with [XXXXXX] and myself this evening to discuss your proposals concerning a future relationship between your Faculty of Integrated Medicine and the new College. As you know, he and I have been asked to represent the College and FIH in this matter. We are aware of difficulties facing your organisations and the FIM DipSIM course. As a consequence of these, it is not possible for the College to enter into an association with you, any of your organisations nor the DipSIM course at the present time. It would, therefore, be wrong to represent to others that any such association has been agreed. You will appreciate that, in these circumstances, you will not receive an invitation to the meeting of 15th April 2010 nor to other planned events. I am sorry to disappoint you in this matter. Yours sincerely |

Conclusions

I’ll confess to feeling almost a little guilty for having appeared to persecute the particular individuals involved in thie episode. But patients are involved and so is the law, and both of these are more important than individuals, The only unfair aspect is that, while it seems that even the Prince of Wales’ Foundation for Integrated Health has rejected Daniel and Atkinson, that Foundation embraces plenty of people who are just as deluded, and potentially dangerous, as those two. The answer to that problem is for the Prince to stop endorsing treatments that don’t work.

As for the University of Buckingham. Well, despite the ‘right wing maverick’ Kealey and the ‘anti-evidence’ Miles, I really think they’ve done the right thing. They’ve listened, they’ve maintained academic rigour and they’ve released all information for which I asked and a lot more. Good for them, I say.

Follow-up

15 April 2010. This story was reported by Times Higher Education, under the title “It’s terminal for integrated medicine diploma“. That report didn’t attract comments. But on 25th April Dr Rosy Daniel replied with “‘Terminal’? We’ve only just begun“. This time there were some feisty responses. Dr Daniel really should check her facts before getting into print.

3 March 2011. Unsurprisingly, Dr Daniel is up and running again, under the name of the British College of Integrated Medicine. The only change seems to be that Mark Atkinson has jumped ship altogether, and, of course, she is now unable to claim endorsement by Buckingham, or any other university. Sadly, though, Karol Sikora seems to have learned nothing from the saga related above. He is still there as chair of the Medical Advisory Board, along with the usual suspects mentioned above.

There is no topic more widely discussed than what one should eat in order to stay healthy. And there are few topics where there evidence is so lacking in quality. This post isn’t about quackery, but about something much more important. it is about the real science (if it merits that description) behind dietary advice. I’m not an expert in nutrition, but I do know a bit about the nature of evidence. I’m continually astonished by the weakness of the evidence for some things that have become received truths, and nowhere is that more true than in nutrition.

|

The BMJ used my review of Gary Taube’s book, The Diet Delusion, to start off their new Round Table feature [full text link to BMJ]. The published version had some big cuts so I publish the original version here. Taubes was kind enough to send me a copy of the book after I’d mentioned his wonderful New York Times piece in my previous excursion into the murky world of diet and health, Diet and health. What can you believe: or does bacon kill you? |

|

The biggest omission in the BMJ version was Taubes’ own ten point summary of his conclusions (on page 454).

"“As I emerge from this research, though, certain conclusions seem inescapable to me, based on existing knowledge

- Dietary fat, whether saturated or not, is not a cause of obesity, heart disease, or any other chronic disease of civilization

- The problem is the carbohydrates in the diet, their effect on insulin secretion, and thus the hormonal regulation of homeostasis – the entire harmonic ensemble of the human body. The more easily digestible and refined the carbohydrates, the greater the effect on our health, weight, and well-being.

- Sugars – sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup specifically – are particularly harmful, probably because the combination of fructose and glucose simultaneously elevates insulin levels while overloading the liver with carbohydrates.

- Through their direct effect on insulin and blood sugar, refined carbohydrates, starches, and sugars are the dietary cause of coronary heart disease and diabetes. They are the most likely dietary causes of cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and the other chronic diseases of civilization.

- Obesity is a disorder of excess fat accumulation, not overeating, and not sedentary behaviour.

- Consuming excess calories does not cause us to grow fatter, any more than it causes a child to grow taller. Expending more energy than we consume does not lead to long-term weight loss; it leads to hunger.

- Fattening and obesity are caused by an imbalance – a disequilibrium – in the hormonal regulation of adipose tissue and fat metabolism. Fat synthesis and storage exceed the mobilization of fat from the adipose tissue and its subsequent oxidation. We become leaner when the hormonal regulation of the fat tissue reverses this balance.

- Insulin is the primary regulator of fat storage. When insulin levels are elevated – either chronically or after a meal – we accumulate fat in our fat tissue. When insulin levels fall, we release fat from our fat tissue and use it for fuel.

- By stimulating insulin secretion, carbohydrates make us fat and ultimately cause obesity. The fewer carbohydrates we consume, the leaner we will be.

- By driving fat accumulation, carbohydrates also increase hunger and decrease the amount of energy we expend in metabolism and physical activity.”

It is on these bases that Taubes suggests that the increase in obesity is, in part, a consequence of the recommendation of a low fat, and hence high sugar diet.

|

The Diet Delusion [ pp 601] (published in the USA as Good Calories, Bad Calories) Gary Taubes 2008 There is no topic more widely discussed than what one should eat in order to stay healthy. And there are few topics where the evidence is so lacking in quality. It is also a topic that is besieged by gurus, cranks and supplement hucksters. You need to beware of misleading titles. Dietitians are good. Nutritionists are sometimes good. But titles like ‘nutritional therapist’ and ‘nutritional medicine’ are usually warning signs of alternative therapists and/or pill salespeople. Gary Taubes is a journalist, but he is quite an exceptional journalist. His account of the importance of randomisation for the establishment of causality is one of the best ever and it was published not in an academic journal, but in the New York Times [1]. His book, The Diet Delusion, is in the same mould. It is more complete and more scholarly than most professional scientists could manage. Not only does it cover the literature right back to Samuel Johnson, but it is also particularly good at unravelling what one might call the politics of science. And by politics I don’t mean the vast lobbying industry that has built up with the aim of selling you unnecessary supplements, but the politics of academia. Obesity sounds simple. If you are fat it is because you eat too much or exercise too little, right? Well no, it’s not as simple as that. For a start, it has been shown time and time again that low fat diets, and exercise, have small and temporary effects on weight. The problem with diet and health revolves round causality. The law of conservation of energy is an inevitable truth, but says nothing about causality. It could imply that you get fat because you eat too much, or equally the causal arrow could point the other way and “we eat more, move less and have less energy to expend because we are metabolically or hormonally driven to get fat”. The assumption that positive caloric balance is the cause of weight gain has predominated since the 1970s and “this simple misconception has led to a century of misguided obesity research”. At the heart of the problem is the paucity of randomised trials, which are the only way to establish causality. Those that there are have usually shown that diet does not matter as much as we are told. Taubes concludes

I think it can certainly be argued that the problem of causality has been greatly underestimated. We are warned constantly of the dangers of processed meat, on the basis of very unconvincing evidence [2]. This is one reason why we still know so little about the causes of obesity, diabetes and heart disease. For Taubes, a major villain was the US nutritionist Ancel Keys (1904 – 2004). His It is quite possible that there was rather more to be said for the Atkins diet than was apparent at the time. The fact that Atkins was not a university scientist, that his views were extreme and that he was so obviously out to make a lot of money from it, gave him all the appearance of being yet another profiteering diet guru. He was dismissed by the medical establishment as a quack. Taubes points out that conflict of interest cuts both ways. Atkins’ sternest critics at Harvard were funded by General Foods, Coca-Cola and the sugar industry. It adds up to a sorry story of a conflict of vested interests and scientific vanity. Taubes’ final judgement is harsh. He quotes Robert Merton’s description [4] of what science is, or should be.

He then comments

It took Taubes five years to write this book, and he has nothing to sell apart from his ideas. No wonder it is so much better than a scientist can produce. Such is the corruption of science by the cult of managerialism that no university would allow you to spend five years on a book [5]. I find all ten points in his summary convincing. But his most important conclusion is that you cannot have any certainty without randomised trials. The business of nutrition is greatly at fault for not having put more effort into organising randomised trials. Until they are done, we’ll never really know, and we shouldn’t pretend that we do. 1. Taubes G. Do we really know what makes us healthy? New York Times 2007 Sep 16.[full text link] [pdf file] 2. Colquhoun, D. (3 May 2009) Diet and health. What can you believe: or does bacon kill you?. 3. Greenberg, S.A.. 2009 How citation distortions create unfounded authority: analysis of a citation network. BMJ ;339:b2680 [pdf file]. 4. Merton, R. K. Behavior Patterns of Scientists . Leonardo, Vol.3 1970; 3(2):213-220. From Jstor [or pdf file] 5. Lawrence PA. The mismeasurement of science. Curr Biol 2007; 17(15):R583-R585.PM:17686424 [pdf file] [commentary] |

If length had allowed, there should certainly have been a reference here to Robert Lustig of UCSF. He is an academic nutritionist who supports the main thesis of Taubes’ book. See, for example, his 2005 review, Childhood obesity: behavioral aberration or biochemical drive? Reinterpreting the First Law of Thermodynamics [full

text link]. Lustig’s slide show, The Trouble with Fructose is available in the NIH web site.

There are a couple of other articles by Taubes that are well worth reading. The Scientist and the Stairmaster Why most of us believe that exercise makes us thinner—and why we’re wrong. Gary Taubes, in New York Magazine, and We can’t work it out, in the Guardian.

You can see Taubes in action on YouTube, for example in “on Cholesterol and Science Practices“, and “on Carbohydrates and Degenerative Diseases“. There is also a video of Taubes on medical grand rounds at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in June 2009. You can see Robert Lustig on YouTube too: “Sugar: The Bitter Truth“.

Follow-up