A.V. Hill

Today we went to see the film Goodbye Christopher Robin. It was very good. I, like most children, read Pooh books as a child.

Image from Wikipedia

I got interested in their author, A.A. Milne, when I discovered that he’d done a mathematics degree at Cambridge. So had my scientific hero A.V. Hill, and (through twitter) I met AV’s granddaughter, Alison Hill. I learned that AV loved to quote A.A.Milne’s poem, OBE.

|

O.B.E. I know a Captain of Industry, I know a Lady of Pedigree, I know a fellow of twenty-three, I had a friend; a friend, and he |

This poem clearly reflects Milne’s experience in WW1. He was at the Battle of the Somme, despite describing himself as a pacifist. In the film he’s portrayed as suffering from PTSD (shell shock as it used to be called). The sound of a balloon popping could trigger a crisis. He was from a wealthy background. He, and his wife Daphne, employed a nanny and maid.

The first Pooh book, When We Were Very Young, came out in 1924, when Milne’s son, Christopher Robin, was four. The nanny is, in some ways, the hero of the film. It was she, not his parents, who looked after Christopher Robin, and the child loved her. In contrast, his parents were distant and uncommunicative.

By today’s standards, Christopher Robin’s upbringing looks almost like child neglect. One can only speculate about how much his father’s PTSD was to blame for this. But his mother had no such excuse. It seems likely to me that part of the blame attaches to the fact that Milne was brought up as an “English gentleman”. Looking after children was a job for nannies, not parents. Milne went to a private school (Westminster), and Christopher Robin was sent to private schools. At 13 he was sent away from his parents, to Stowe school, where he suffered a lot of bullying. That is a problem that’s endemic and it’s particularly bad in private boarding schools.

I have seen it at first hand. I went to what was known at the time as a direct grant school, and I was a day boy. But the school did its best to ape a private school. It was a cold and cruel place. Once, I came off my bike and went head first into a sandstone wall. While recovering in the matron’s room I looked at some of the books there. They were mostly ancient boys’ stories that lauded the virtues of the British Empire. Even at 13, I was horrified.

After he reached the age of 9, Christopher Robin resented increasingly what he came to see as his parents’ exploitation of his childhood. After WW2, Christopher Robin got married but his parents didn’t approve of his choice. He became estranged from his parents, and went to run a bookshop in Dartmouth (Devon). Once his father died, he did not see his mother during the 15 years that passed before her death. Even when she was on her deathbed, she refused to see her son.

It’s a sad story, and the film conveys that well. I wonder whether it might have been different if it were not for the horrors of WW1 and the horrors of the upbringing of English gentlemen.

It would be good to think that things were better now. They are better, but the old problems haven’t vanished. The UK is still ruled largely by graduates from Oxford and Cambridge. They take mostly white kids from expensive private schools. These institutions specialise in giving people confidence that exceeds their abilities. Now the UK is mocked across the world for its refusal to modernise and for the delusions of empire that are brexit. The New York Times commented

if what the Brexiteers want is to return Britain to a utopia they have devised by splicing a few rose-tinted memories of the 1950s together with an understanding of imperial history derived largely from images on vintage biscuit tins,

Just look at at this recent New Yorker cover. Look at Jacob Rees-Mogg. And look at Brexit.

Follow-up

I have always been insanely proud to work at UCL. My first job was as an assistant lecturer. The famous pharmacologist, Heinz Otto Schild gave me that job in 1964, and apart from nine years, I have been there ever since. That’s 50 years. I love its godless tradition. I love its multi-faculty nature. And I love its relatively democratic ways (with rare exceptions).

|

From the start, the intellectual heart of UCL has been the staff Common Room. As I so often say, failing to waste time drinking coffee with people who are cleverer than yourself can seriously damage your career (and your happiness). And there’s no better place for that than the Housman room. |

|

It is there that I met the great statistician Alan Hawkes, without whom much of my research would never have happened. It was there that Hyman Kestelman (among others) gave me informal tutorials on matrix algebra over lunch. It was there where I have met John Sutherland (English), Mary Fulbrook (German), many historians and people from the Slade school of Art. And it was there where, yesterday, I had an illuminating conversation with Steve Jones about the problems of twin studies for measuring heritability.

I was astonished when I arrived at UCL to discover that the Housman room was male only. I’d just come from Edinburgh which still had separate men’s and women’s student unions and some men-only bars. But Edinburgh also had a wonderful staff club, open to all. It’s true that UCL had also a women-only common room and a mixed common room, the Haldane room (which is where I went usually). But the biggest and most impressive room, the Housman room, was for men only. I found this very odd in the 1960s, the age of sexual liberation. Reform was in the air in the 1960s.

A lot of other people, not all female, thought it odd too. Direct action was called for (I was in CND at the time). So we’d go into the Housman room with a woman and join the queue for coffee. It never took long before some pompous prat would tap the woman on the shoulder and eject her. I can’t remember now the names of any of the feisty women who braved the lions’ den (perhaps this blog will remind someone).

|

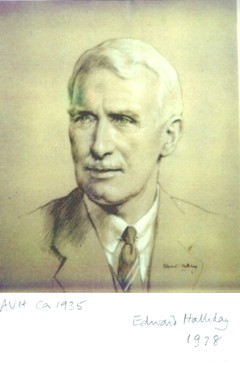

I had any ally in Brian Woledge. He was Fielden Professor of French at UCL from 1939 (when I was 3) to 1971 so he was on the brink of retirement. I was a young lecturer, but our thinking on segregation was much the same. His obituary in the Guardian says “Of robustly secular beliefs and Fabian views, in important respects he was an heir to the ideals of the Enlightenment”. It’s no wonder we got on well. The picture, from around 1970, was supplied by his son, Roger Woledge, who was in the Physiology department at UCL for most of his life, and who did his PhD with my great hero, A.V. Hill. |

|

In 1967 we proposed a motion at the Housman AGM to desegregate all common rooms. It was defeated. The next year we did it again, and were defeated again.. But at the third attempt, in 1969, we succeeded. I was very happy to have had a small role in upholding UCL’s liberal traditions.

|

It is now quite impossible to imagine that UCL was segregated. After all, UCL was the first English university to admit women on equal terms to men, in 1878 (the Scots were a bit ahead) And UCL was home to Kathleen Lonsdale (1903 -1971), one of the first two female fellows of the Royal Society, and the first female professor at UCL. |

|

Nevertheless, in the mid-1960s, women were very far from being regarded as equal, even at UCL. At the time, segregation was more common than people now remember.

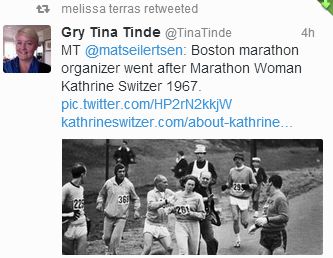

I was spurred to write this post when Melissa Terras, UCL’s professor of digital humanities, retweeted a reminder that it was in 1967 that a woman first ran in a an official marathon, and suffered physical attack from a male organiser for her temerity.

I responded

I was urged to record this history by both Terras and by Lisa Jardine, Director of UCL’s Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in the Humanities. So I have done it.

I was very aware of Kathy Switzer at the time, and I’ve no doubt she is part of the reason why I felt strongly about segregation. You can read about the 1967 Boston marathon in her own words. I thought it was a wonderful story, though I wasn’t yet into distance running myself (I was still sailing and boxing).

One of the great thing about marathons is that women and men run in the same race. That means that almost all men have had to get used to being overtaken by very many women. That has been wonderfully good for deflating male egos. When I was training for marathons in the 1980s, my training partner, Annie Briggs was on the elite start -a good hour faster than I could manage.

|

Now we are accustomed to watching Paula Radcliffe run marathons faster than any but the very best men. She’s the world record holder with the spectacular time of 2 hours 15 min in the 2003 London Marathon (my best is 3 hr 57 min). That’s only a bit over 26 consecutive 5 minute miles. And that’s faster than I could run a single mile at my peak.[Picture from Wikipedia: NYC marathon 2008 2:23:56] |

|

It’s now utterly beyond belief that in the 1960s men were saying that women were too feeble to run 26 miles. It was sheer blind arrogance. After Switzer, progress was fast. In 1972 women were allowed to run in Boston, and within 10 years, the women’s record time had fallen by a full hour. Physiology hadn’t changed, but confidence had.

Of course it wasn’t until the 2012 Olympics that women gained total equality in sport. Everyone who said that women were incapable of competing in combat sports should see Rosi Sexton in action.

She’s the ultimate high-achiever. She’s an accomplished musician (grade 7 cello, ALCM piano) and she played at the Albert Hall with the Reading Youth Orchestra. She went on to get a first in maths (Cambridge, Trinity College), where her tutor was Tim Gowers. Then she did a PhD in theoretical computer science from Manchester (read her thesis). And she’s had a distinguished career as professional athlete, competing at the highest level in MMA. Why? “The other things I did, the music, the maths, just weren’t quite hard enough“.

Not many athletes have a paper in the Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra. I’d be very happy if I could do any one of these things as well as she does.

|

It could not be more appropriate than to be writng this in the week when the Fields medal was won by a woman, Maryam Mirzakhani, for the first time since it started, in 1936. Genetics hasn’t changed since 1936. Confidence has. UCL mathematician, Helen Wilson, points out the encouragement this will give to female mathematicians. |

|

On 15 July 2017, Maryam Mirzakhani died, at a mere 40 years old. It’s tragic that having achieved so much, against all the odds, the dice rolled the wrong way for her, and cancer destroyed her. Her life will inspire generations to come.

As in marathons, confidence, role models and zeitgeist matter as much as genetics.

It’s examples like these that have made me profoundly suspicious of generalisations about what particular groups of people can and cannot do. Whether it is working class boys. black boys, or women, such generalisations can be shattered over a decade or two, once the zeitgeist changes.

That’s one reason that I am so unsympathetic to the IQ enthusiasts. Great harm has stemmed from the belief that it’s possible to sum up human achievements in a single number. What’s more, it’s a number that measures your resemblance to white male psychologists. It is because politicians believed the over-hyped claims of psychologists in the 1930s, that three-quarters of the population was written off. Much the same thing has happened with women, and with skin colour.

Don’t believe it.

And the job of desegregation may not be entirely finished. In fact now it is harder to combat, since it’s unspoken. Once again, I’m reminded of Peter Lawrence’s essay, The Mismeasurement of Science. Speaking of the perverse incentives and over-competitiveness that has invaded academia, he says

“Gentle people of both sexes vote with their feet and leave a profession that they, correctly, perceive to discriminate against them [17]. Not only do we lose many original researchers, I think science would flourish more in an understanding and empathetic workplace.”

The perverse incentives that make academic life hard for women (and for many men too) are administered by HR departments (with the collusion of mostly elderly male academics). They are the very same people who write fine-sounding diversity documents and lecture you about work-life balance.

It’s time they woke up.

Note. The minutes of Housman AGMs from the 1960s are missing at the moment. If they come to light, this post will be modified accordingly.

Follow-up

29 August 2014

|

As I’d hoped, this post elicited the name of one of the women who braved the rules and went into the Housman room when it was still men-only. I had an email from Lynn Bindman, and she told me that one of them was Gertrude Falk (1925 – 2008), who had worked in Bernard Katz’s Biophysics Department since 1961. |

In 1967 she must have been about 42. The episode is mentioned in Gertrude’s obituary in the Guardian. She also sent me a copy of the Physiologocal Society’s obituary, which recounts the story thus.

“Her indifference to conventions is well illustrated by the occasion when, drinking coffee in the men’s staff common room, at that time still segregated, she responded calmly to the Beadle summoned to escort her out, “well, I am certainly going to finish my coffee first”, and did so at her leisure.”

I have another story about Gertrude’s feistiness. Every year the Royal Society has a soirée for fellows and guests. It’s a sort of private view for the Summer Science exhibition. Men are required to dress like penguins despite the heat, and the invitation says “decorations will be worn”. The food is good though it’s all a bit pompous for my taste. Some years ago I met Gertrude at a soirée and I saw she was wearing a medal round her neck. I said “have they made you a Dame of the British Empire?”. She held up the medal and I saw it said “Erasmus High School Economics Prize”. She is why I usually go to the soirée wearing my London Marathon medal.

12 May 2015

Surprising as it seems now that the Housman room excluded women until 1969, there are other UCL institutions that were almost as slow as Oxford and Camridge to join the modern age.

One of these is the Professors’ Dining Club (it isn’t actually restricted to professors). I recall going to one of their dinners in the 1960s, as a guest of Heinz Otto Schild, the then head of Pharmacology, who gave me my first job. He was a lovely man, but I was horrified that it didn’t allow women to join. I recently discovered that its records reveal that it didn’t see the light until 1981. It wasn’t until after that happened that I joined the club. It seems now to be a shameful record.

|

One of my greatest scientific heros is A.V.Hill, and its one of my great regrets that I saw him only in the distance. He’s a hero partly because of his science, but also because of his other interests, in particular his efforts to help scientists escape from pre-war Germany. Read the Biographical Memoir of Hill, written by Bernard Katz [download pdf], and comments in my obituary for Katz.

A.V. Hill, c. 1935 (drawn by Edward Halliday in 1978, from a photograph) |

|

There are some amazing pictures from Hill’s photo album here. And you can read an account of a visit to the lab on Boxing Day 1960 written by AV’s grandson, Nicholas Humphrey (his father, John Humphrey, was external examiner of my PhD). And Tom Chivers, who writes a rather good column in the Telegraph is Alison Hill’s son, and so he’s the great grandson of AV. In yet another irrelevant coincidence, I lived for a year in a Max Planck Institute house that had previously been occupied by Otto Meyerhof who, in 1922, got the Nobel prize jointly with AV Hill.

Some of the scientific background is given by Austin Elliott, as I did in The quantitative analysis of drug–receptor interactions: a short history.

This post was prompted not so much by the science as by the curious conjunction of the New Year’s Honours List, and a discovery from Twitter. Hill won the Nobel prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1922, but refused the customary knighthood or peerage that gets offered on such occasions. Dr Alison Hill, AV’s granddaughter, mentioned on Twitter that Hill loved quoting a verse by A.A. Milne (author of Winnie the Pooh) that I had never heard before. It appears to come from a book, The Sunny Side, that Milne publshed in 1921. It’s worth quoting in full.

|

O.B.E. I know a Captain of Industry, I know a Lady of Pedigree, I know a fellow of twenty-three, I had a friend; a friend, and he |

This also led to the unexpected discovery that A.A. Milne, like A.V. Hill, had done a mathematics degree at Trinity College Cambridge before moving on to teddy bears.

Wikepedia gives a list of the alternative roll of honour, those who have declined an honour.

The list of honours in Higher Education contains the usual administrators and vice-chancellors. It contains next to no scientists. I can’t say i find it very inspiring. The main effect of the honours system seems to be to keep people from rocking the boat until the day they die.

One is once again reminded of the definition from A Sceptic’s Medical Dictionary (BMJ publishing, 1997). by Michael O’Donnell.

Knight starvation

“Affective disorder that afflicts senior doctors . . . A progressive condition that deteriorates with the publication of each Honours List and, in longstanding cases, can produce serious erosion of judgement and integrity.”

Here’s a 1932 picture with several scientific heros. Hill is in the centre, with A.J. Clark on his left and Verney on his right, J.H.Gaddum is on the left end of the back row (all holders of the UCL chair in Pharmacology). .

Taken from K J Franklin’s History of the International Physiological Congress – it is a photo taken on the SS Minnekhda, charted by European physiologists to attend the 1932 Boston congress. [Dr Tilli Tansey, FMedSci., Hon FRCP.,Historian of Modern Medical Sciences Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine, UCL

Follow-up

Here are two more documents that are relevant to the life of A.V. Hill.

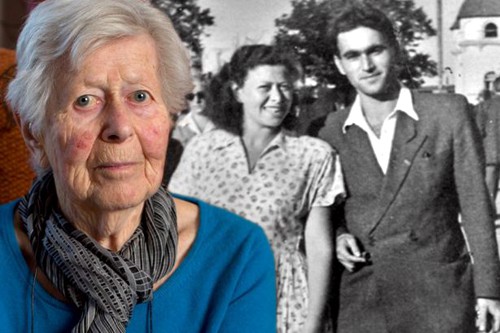

Gerta Vrbová (born 1926, in Slovakia) wrote "Archibald V. Hill’s contribution to science and society" [download pdf]. She herself lived through the holocaust. The story of her escape to England is like an adventure novel. She became a professor at UCL where I met her many times.

" as an academic she was able to gain permission to travel between the Soviet states of Eastern Europe, and on a visit to a conference in Poland in 1958, she decided to make her escape. Travelling on foot across the mountains back to Czechoslovakia, she collected her children aged four and six, crossed the Polish Czechoslovak border with them and took a train to Warsaw. Having unofficially entered the names of children on her passport, she was able to obtain a transit visa for Copenhagen, from where, after a year, she was able finally to come to England." [from UCL news]

Gerta Vrbová in 2014, and with husband, Rudolf Vrba, in Bratislava after the war [picture from Daily Mirror]

There is another interview with Vrbová in the Physiological Society’s Oral History series.

A.V. Hill and alphabetical order of authors

In the first 50 years of its existence, the Journal of Physiology allowed authors to choose the order in which authors appeared, But for 60 years, from the 1930s to the 1990s, the journal insisted that authors’ names be listed in alphabetical order. That, for example, is why our 1985 paper is listed as Colquhoun & Sakmann. A.V.Hill was one of the people who proposed this system and a history of it has appeared recently [download pdf]. Personally, I liked this system. though having a name that begins the "C", I couldn’t be very active in advocating it. The alphabetical system worked well when authors did experiments themselves, and most papers had 1 – 3 authors. Nobody judges contributions based on author order for Hodgkin & Huxley, or for Katz & Miledi. In the 1990s, alphabetical order was abandoned. Too few other journals used that system, and it could not survive the era of guest authors that has accompanied the publish-or-perish regime imposed on academics by managers.

2 February 2017

A.V. Hill is one of my scientific heroes, because of his science, his humanity, his running (and because he turned down a knighthood after he got the Nobel Prize in 1922 -see above.

Hilda Bastian has written a timely article about him:The same folly,the same fury. It was posted shortly after Holocaust Memorial Day (27 January), the day on which Donald Trump chose to exclude from the USA all the refugees who are fleeing from the war in Syria.

AV Hill played a central role in helping German scientists escape from the Nazis -to the enormous benefit of UK science. He spoke from the same stage as Mussolini.

He said

“Freedom itself is again at stake… It is difficult to believe in progress, at least in decency and commonsense, when this can happen almost in a night in a previously civilised State… [W]e must ensure that the same folly, the same fury, does not occur elsewhere.” A.V. Hill (Nature, 1933).

The post doesn’t mention Trump, Farage or May. It doesn’t need to.