Pittilo

The long-awaited government decision concerning statutory regulation of herbalists, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and acupuncture came out today.

Get the Department of Health (DH) report [pdf]

It is not good news. They have opted for statutory regulation by the Health Professions Council (HPC). This is much what was recommended by the disgraceful Pittilo report, about which I wrote a commentary in the Times (or free version here), and A very bad report: gamma minus for the vice-chancellor.

The DH report is merely an analysis of responses to the consultation, but the MHRA says

"The Health Professions Council (HPC) has now been asked to establish a statutory register for practitioners supplying unlicensed herbal medicines. The proposal is, following creation of this register, to make use of a derogation in European medicines legislation (Article 5 (1) of Directive 2001/83/EC) that allows national arrangements to permit those designated as “authorised healthcare professionals” to commission unlicensed medicines to meet the special needs of their patients."

The MHRA points out that this started 11 years ago with the publication of the House of Lords report (2000). Both that report, and the government’s response to it, set the following priorities. Both state clearly

“… we recommend that three important questions should be addressed in the following order . .

- (1) does the treatment offer therapeutic benefits greater than placebo?

- (2) is the treatment safe?

- (3) how does it compare, in medical outcome and cost-effectiveness, with other forms of treatment?

The report of DH and the MHRA’s response have ignored totally two of these three requirements. There is no consideration whatsoever of whether treatments work better than placebo (point one) and there is no consideration whatsoever of cost-effectiveness (point 3). These two important recommendations in the Houss of Lords report have simply been brushed under the carpet.

Needless to say, herbalists are head over heels with joy at this sign of official endorsement (here is one reaction)

Here are my first reactions. The post will be updated soon.

The DH report is, in a sense, democratic. They have simply counted the responses, for and against each proposal. They seem to be quite unaware that most of the responses come from High Street herbailsts whose main aim is to gain respectability. The response of the Academy of Royal Medical Colleges counts as one vote, just the same as the owner of a Chinese medicine shop. This is not how health policy should be determined. Some intervention of the brain is needed, but that isn’t apparent in the report.

At present the HPC regulates Arts therapists, biomedical scientists, chiropodists/podiatrists, clinical scientists, dietitians, occupational therapists, operating department practitioners, orthoptists, paramedics, physiotherapists, prosthetists/orthotists, radiographers and speech & language therapists. I shudder to think what all these good people will think about being lumped together with people who practice evidence-free medicine (or, worse, forms of medicine where there is good evidence that they don’t work).

The vast majority of herbalists, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and acupuncture has no good evidence that it works, In the case of soem herbal medicines and acupuncture, there is good evidence that they don’t work. Yet the HPC has, as one of its criteria, that aspiring to be regulated by them requires

"practise based on evidence of efficacy"

The Department of Health seems to have quietly forgotten about this criterion. It cannot possibly be met. The HPC has already expressed its willingness to go along with this two-faced approach (see Health Professions Council ignores its own rules: the result is nonsense )

Another mistake made by the Department of Health regards the value of "training". The report (page 11) says

Would statutory regulation lessen the risk of harm? (Q2)

Again, the vast majority of respondents thought it would. Reasons given were that statutory regulation would ensure that herbal practitioners and acupuncturists are carefully and thoroughly trained. That training is subject to accreditation, evaluation and periodic review by independent educational and training professionals, and disciplinary oversight by a regulating body. Incompetent or unscrupulous practitioners could be struck off the register and prevented from practising.

Although it is pointed out to them in several responses, the Department of Health seems quite incapable of understanding a simple and obvious truth. Spending three years training people to learn things that are not true, safeguards nobody. On the contrary, it endangers the public. Training in nonsense is obviously a nonsense.

At the end of the report is a list of organisations who responded, As expected, they are predominantly trade bodies that have a vested interest in allowing thinks to be sold freely regardless of whether they work or not. The first four are Alliance of Herbal Medicine Practitioners. European herbal and Traditional Medicine Practitioners Association (ETMPA), Association Chinese Medicine Practitioners (UK) (ACMP) and Acupuncture Society. And so on.

More coming soon.

Follow-up

16 February 2011. Later the same day, we see one reason why Michael Mcintyre, chair of the European Herbal Practitioners Association, got what he wanted to promote his trade. They had evidently hired a PR Agency, Cogitamus, to push their case. Now they are crowing about their victory. And of course his profits were not harmed by the free publicity that was given to his cause by the BBC,

The pinheads in the Department of Health are more easily persuaded by a PR agency than by any number of people who know a lot more about it, and who have no profit motive.

17 February 2011.

The herbal problem was front page news in the London free paper, the Metro: Chinese medicine and herbal ban to see Britain defy EU laws

The Daily Telegraph covered the story: Herbal medicine to be regulated, says Andrew Lansley. The comments featured some pretty mad rants from herbalists, to which I tried to reply.

The Metro article elicited a fine bit of abuse from a Lynda Kane. I’m constantly amazed at the downright viciousness of cuddly holistic therapists when they get found out. I guess it is just another bad case of cognitive dissonance. I can’t resist a few quotations.

Sir,

“I have just come across your asinine comments quoted in the London Metro newspaper re the EU herbal medicine directive. For a supposed scientist your mis-informed, closed-minded, unsubstantiated bigotry leaves me speechless”

“As a scientist myself, I abide by the virtues of open-minded neutrality and accepting the hypothesis until proven otherwise by null-hypothesis based research.”

“How many of the innumerable studies on the efficacy of herbal medicine have you read? “

“Perhaps in your ‘day’ professors could say whatever they liked and be listened to. That day is long gone, as you must know from the various law-suits you have been party to.”

I love the idea that statistics allow you to accept any hypothesis whatsoever until someone shows it to be wrong.

This would be funny if it were not so sad (and rather painful). As always I replied politely and referred her to NCCAM’s Guide to Herbs, so she can check up on that plethora of evidence that she seems to think exists.

This is Lynda Kane of energyawareness.org. I can recommend her web site, if you want some truly jaw-dropping woo. She’ll sell you a “White Jade Energy Egg – may provide up to 5 times as much protection from wifi and from other peoples’ energies – costs £47.00”. Hmm, sounds good. How does it work? Easy.

“The human energy or “qi” field is shaped like an egg. It is being attacked by many forms of natural and man-made environmental stress 24 hours a day.”

I guess that’s OK according to Ms Kane’s interpretation of statistics which allows you to accept any hypothesis whatsoever until someone shows it to be wrong.

Anyone for Trading Standards or the ASA?

17 February 2011. The excellent Andy Lewis has posted on similar problems “How to Spot Bad Regulation of Alternative Medicine“

.20 July 2013

Nothing visible happened after this announcement. Until the government’s resident medical loon, David Tredinnick MP forced a debate on the matter. His introduction to the debate was his usual make-believe. Sadly it made much of an exhibit at the Royal Society Summer Science exhibition -a bit of bait and swich by aromatherapists.

After ploughing your way through pages of nonsense, you get to the interesting bit. At 10.38 am, The Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Health, Dr Daniel Poulter, announced what was happening. It seems that there may, after all, have been some effect of all the sensible submissions which pointed out the impossibility of regulating nonsense. The question of regulation has, yet again, been postponed.

"To ensure that we take forward the matter effectively, we want to bring together experts and interested parties from all sides of the debate to form a working group that will gather evidence and consider all the viable options in more detail,"

One wonders who will be on this working group? If they don’t choose the right people, it could be as bad as the Pittilo report. It wasn’t reassuring to read

" we want to set up a working group and to work with my hon. Friend [Tredinnick], and herbalists and others, to ensure that the legislation is fit for purpose."

Every single request for information about course materials in quack medicine that I have ever sent has been turned down by universities,

It is hardly as important as as refusal of FoI requests to see climate change documents, but it does indicate that some vice-chancellors are not very interested in openness. This secretiveness is exactly the sort of thing that leads to lack of trust in universities and in science as a whole.

The one case that I have won took over three years and an Information Tribunal decision against the University of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) before I got anything.

UCLAN spent £80,307.95.(inc VAT at 17.5%) in legal expenses alone (plus heaven knows how much in staff time) to prevent us from seeing what was taught on their now defunct “BSc (Hons) homeopathy”. This does not seem to me to be good use of taxpayers’ money. A small sample of what was taught has already been posted (more to come). It is very obvious why the university wanted to keep it secret, and equally obvious that it is in the public interest that it should be seen.

UCLAN had dropped not only its homeopathy "degree" before the information was revealed, They also set up an internal inquiry into all the rest of their courses in magic medicine which ended with the dumping of all of them.

Well, not quite all, There was one left. An “MSc” in homeopathy by e-learning. Why this was allowed to continue after the findings of UCLAN’s internal review, heaven only knows. It is run by the same Kate Chatfield who ran the now defunct BSc. Having started to defend the reputation against the harm done to it by offering this sort of rubbish, I thought I should finish. So I asked for the contents of this course too. It is, after all, much the same title as the course that UCLAN had just been ordered to release. But no, this request too was met with a refusal

Worse still, the refusal was claimed under section 43(2) if the Freedom of Information Act 2000. That is the public interest defence, The very defence that was dismissed in scathing terms by the Information Tribunal less than two months ago,

To add insult to injury, UCLAN said that it would make available the contents of the 86 modules in the course under its publication scheme, at a cost of £20 per module, That comes to £1,720 for the course, Some freedom of information.

Because this was a new request, it now has to go through the process of an internal reviw of the decision before it can ne referred to the Information Commissioner. That will be requested, and since internal reviews have, so far, never changed the initial judgment. the appeal to the Information Commissioner should be submitted within the month. I have been promised that the Information Commissioner will deal with it much faster this time than the two years it took last time.

And a bit more unfreedom

Middlesex University

I first asked Middlesex for materials from their homeopathy course on 1 Oct 2008. These courses are validated by Middlesex university (MU) but actually run by the Centre for Homeopathic Education. Thw MU site barely mentions homeopathy and all I got was the usual excuse that the uninsersity did not possess the teaching materials. As usual, the validation had been done without without looking at what was actually being taught. The did send me the validation document though [download it] As usual, the validation document shows no sign at all of the fact that the usbject of the "BSc" is utter nonsense. One wonderful passage says

“. . . the Panel were assured that the Team are clearly producing practitioners but wanted to explore what makes these students graduates? The Team stated that the training reflects the professional standards that govern the programme and the graduateness is achieved through developing knowledge by being able to access sources and critically analyse these sources . . . “

Given that the most prominent characteristic of homeopaths (and other advocates of magic medicine) is total lack of critical ability, this is hilarious. If they had critical ability they wouldn’t be homeopaths. Hilarious is not quite the right word, It is tragic that nonsense like this can be found in an official university document.

Middlesex, though it doesn’t advertise homeopathy, does advertise degrees in Traditional Chinese Medicine, Herbal Medicine and Ayurveda. On 2nd February 2010 I asked for teaching materials from these courses. Guess what? The request was refused. In this case the exemptions under FOIA were not even invoked but I was told that "All these materials are presently available only in one format at the University – via a student-only accessed virtual learning environment. ". Seems that they can’t print out the bits that I asked for, The internal review has been requested, then we shall see what the Information Commissioner has to say.

Two other cases are at present being considered by the Information Commissioner (Scotland), after requests under the Scottish FoIA were refused. They are interesting cases because they bear on the decision, currently being considered by the government, about whether they should implement the recommendations of the execrable Pittilo report.

Napier University Edinburgh. The first was for teaching material form the herbal medicine course at Napier University Edinburgh. I notice that this course no longer appears in UCAS or on Napier’s own web site, so maybe the idea that its contents might be disclosed has been sufficient to make the university do the sensible thing.

Robert Gordon University Aberdeen The second request was for teaching material from the “Introduction to Homeopathy” course at the Robert Gordon University Aberdeen. The particular interest that attaches to this is that the vice-chancellor of Robert Gordon university is Michael Pittilo. The fact that he is willing to tolerate such a course in his own university seems to me to disqualify him from expressing any view on medical subjects.

Michael Pittilo, Crohn’s disease and Andrew Wakefield

Michael Pittilo has not been active in science for some time now, but Medline does show scientiifc publications for Pittilo RM, between 1979 anf 1998. Between 1989 and 1995 there are five papers published jointly with one Andrew Wakefield. These papers alleged a relationship between measles virus and Crohn’s disease. The papers were published before tha infamous 1998 paper by Wakefield in the Lancet (now retracted) that brought disgrace on Wakefield and probably caused unnecessary deaths.. The link between measles and Crohn’s disease is now equally disproved.

The subject has been reviewed by Korzenik (2005) in Past and Current Theories of Etiology of IBD. Toothpaste, Worms, and Refrigerators

“Wakefield et al proposed that Crohn’s results from a chronic infection of submucosal endothelium of the intestines with the measles virus [Crohn’s disease: pathogenesis and persistent measles virus infection. Wakefield AJ, Ekbom A, Dhillon AP, Pittilo RM, Pounder RE., Gastroenterology, 1995, 108(3):911-6]”

"This led to considerable media interest and< public concern over use of live measles vaccine as well as other vaccines. A number of researchers countered these claims, with other studies finding that titers to measles were not increased in Crohn’s patients, granulomas were not associated with endothelium 49 , measles were not in granulomas50 and the measles vaccine is not associated with an increased risk of Crohn’s disease51–55 "

This bit of history is not strictly relevant to the Pittilo report, but I do find quite puzzling how the government chooses people from whom it wishes to get advice about medical problems.

Follow-up

I notice that the Robert Gordon university bulletin has announced that

“Professor Mike Pittilo, Principal of the University, has been made an MBE in the New Year Honours list for services to healthcare”.

That is a reward for writing a very bad report that has not yet been implemented, and one hopes, for the sake of patients, will never be implemented. I do sometimes wonder about the bizarre honours system in the UK.

Postcript.

On 16th February, the death of Michael Pittilo was announced. He had been suffeing from cancer and was only 55 years old. I wouldn’t wish that fate on my worst enemy.

The Yuletide edition of the BMJ carries a lovely article by Jeffrey Aronson, Patent medicines and secret remedies. (BMJ 2009;339:b5415).

I was delighted to be asked to write an editorial about it, In fact it proved quite hard work, because the BMJ thought it improper to be too rude about the royal family, or about the possibility of Knight Starvation among senior medics. The compromise version that appeared in the BMJ is on line (full text link).

The changes were sufficient that it seems worth posting the original version (with links embedded for convenience).

The cuts are a bit ironic, since the whole point of the article is to point out the stifling political correctness that has gripped the BMA, the royal colleges, and the Department of Health when it comes to dealing with evidence-free medicine. It has become commonplace for people to worry about the future of the print media, The fact of the matter is you can often find a quicker. smarter amd blunter response to the news on blogs than you can find in the dead tree media. I doubt that the BMJ is in any danger of course. It has a good reputation for its attitude to improper drug company influence (a perpetual problem for clinical journals) as well as for clinical and science articles. It’s great to see its editor, Fiona Godlee, supporting the national campaign for reform of the libel laws (please sign it yourself).

The fact remains that when it comes to the particular problem of magic medicine, the action has not come from the BMA, the royal colleges, and certainly not from the Department of Health, It has come from what Goldacre called the “intrepid, ragged band of bloggers”. They are the ones who’ve done the investigative journalism, sent complaints and called baloney wherever they saw it. This article was meant to celebrate their collective efforts and to celebrate the fact that those efforts are beginning to percolate upwards to influence the powers that be.

It seems invidious to pick on one example, but if you want an example of beautiful and trenchant writing on one of the topics dealt with here, you’d be better off reading Andrew Lewis’s piece "Meddling Princes, Medical Regulation and Licenses to Kill” than anything in a print journal.

I was a bit disappointed by removal of the comment about the Prince of Wales. In fact I’m not particularly republican compared with many of my friends. The royal family is clearly good for the tourist industry and that’s important. Since Mrs Thatcher (and her successors) destroyed large swathes of manufacturing and put trust in the vapourware produced by dishonest and/or incompetent bankers, it isn’t obvious how the UK can stay afloat. If tourists will pay to see people driving in golden coaches, that’s fine. We need the money. What is absolutely NOT acceptable is for royals to interfere in the democratic political process. That is what the Prince of Wales does incessantly. No doubt he is well-meaning, but that is not sufficient. If I wanted to know the winner of the 2.30 at Newmarket, it might make sense to ask a royal. In medicine it makes no sense at all. But the quality of the advice is irrelevant anyway. The royal web site itself says “As a constitutional monarch, the Sovereign must remain politically neutral.”. Why does she not apply that rule to her son? Time to put him over your knee Ma’am?

Two of the major bits that were cut out are shown in bold, The many other changes are small.

BMJ editorial December 2009

Secret remedies: 100 years onTime to look again at the efficacy of remedies Jeffrey Aronson in his article [1] gives a fascinating insight into how the BMA, BMJ and politicians tried, a century ago, to put an end to the marketing of secret remedies. They didn’t have much success. The problems had not improved 40 years later when A.J. Clark published his book on patent medicines [2]. It is astounding to see how little has changed since then. He wrote, for example, “On the other hand the quack medicine vendor can pursue his advertising campaigns in the happy assurance that, whatever lies he tells, he need fear nothing from the interference of British law. The law does much to protect the quack medicine vendor because the laws of slander and libel are so severe.”> Clark himself was sued for libel after he’d written in a pamphlet “ ‘Cures’ for consumption, cancer and diabetes may fairly be classed as murderous”. Although he initially tried to fight the case, impending destitution eventually forced him to apologise [3]. If that happened today, the accusation would have been repeated on hundreds of web sites round the world within 24 hours, and the quack would, with luck, lose [4]. As early as 1927, Clark had written “Today some travesty of physical science appears to be the most popular form of incantation” [5]. That is even more true today. Homeopaths regularly talk utter nonsense about quantum theory [6] and ‘nutritional therapists’ claim to cure AIDS with vitamin pills or even with downloaded music files. Some of their writing is plain delusional, but much of it is a parody of scientific writing. The style, which Goldacre [7] calls ‘sciencey’, often looks quite plausible until you start to check the references. A 100 years on from the BMA’s efforts, we need once again to look at the efficacy of remedies. Indeed the effort is already well under way, but this time it takes a rather different form. The initiative has come largely from an “intrepid, ragged band of bloggers” and some good journalists, helped by many scientific societies, but substantially hindered by the BMA, the Royal Colleges, the Department of Health and a few vice-chancellors. Even NICE and the MHRA have not helped much. The response of the royal colleges to the resurgence in magic medicine that started in the 1970s seems to have been a sort of embarrassment. They pushed the questions under the carpet by setting up committees (often populated with known sympathizers) so as to avoid having to say ‘baloney’. The Department of Health, equally embarrassed, tends to refer the questions to that well-known medical authority, the Prince of Wales (it is his Foundation for Integrated Health that was charged with drafting National Occupational Standards in make-believe subjects like naturopathy [8]. Two recent examples suffice to illustrate the problems. The first example is the argument about the desirability of statutory regulation of acupuncture, herbal and traditional Chinese medicine (the Pittilo recommendations) [9]. Let’s start with a definition, taken from ‘A patients’ guide to magic medicine’ [10]. “Herbal medicine: giving patients an unknown dose of an ill-defined drug, of unknown effectiveness and unknown safety”. It seems to me to be self-evident that you cannot start to think about a sensible form of regulation unless you first decide whether what you are trying to regulate is nonsense, though this idea does not seem to have penetrated the thinking of the Department of Health or the authors of the Pittilo report. The consultation on statutory regulation has had many submissions [11] that point out the danger to patients of appearing to give official endorsement of treatments that don’t work. The good news is that there seems to have been a major change of heart at the Royal College of Physicians. Their submission points out with admirable clarity that the statutory regulation of things that don’t work is a danger to patients (though they still have a blank spot about the evidence for acupuncture, partly as a result of the recent uncharacteristically bad assessment of the evidence by NICE [12]). Things are looking up. Nevertheless, after the public consultation on the report ended on November 16th, the Prince of Wales abused his position to make a well-publicised intervention on behalf of herbalists [13]. Sometimes I think his mother should give him a firm lesson in the meaning of the term ‘constitutional monarchy’, before he destroys it. The other example concerns the recent ‘evidence check: homeopathy’ conducted by the House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee (SCITECH). First the definition [10]: “Homeopathy: giving patients medicines that contain no medicine whatsoever”. When homeopathy was dreamt up, at the end of the 18th century, regular physicians were lethal blood-letters, and it’s quite likely that giving nothing saved people from them. By the mid-19th century, discoveries about the real causes of disease had started, but homeopaths remain to this day stuck in their 18th century time warp. In 1842 Oliver Wendell Holmes said all that needed to be said about medicine-free medicine [14]. It is nothing short of surreal that the UK parliament is still discussing it in 2009. Nevertheless it is worth watching the SCITECH proceedings [15]. The first two sessions are fun, if only for the statement by the Professional Standards Director of Boots that they sell homeopathic pills while being quite aware that they don’t work. I thought that was rather admirable honesty. Peter Fisher, clinical director of the Royal Homeopathic Hospital, went through his familiar cherry-picking of evidence, but at least repeated his condemnation of the sale of sugar pills for the prevention of malaria. But for pure comedy gold, there is nothing to beat the final session. The health minister, Michael O’Brien, was eventually cajoled into admitting that there was no good evidence that homeopathy worked but defended the idea that the taxpayer should pay for it anyway. It was much harder to understand the position of the chief scientific advisor in the Department of Health, David Harper. He was evasive and ill-informed. Eventually the chairman, Phil Willis, said “No, that is not what I am asking you. You are the Department’s Chief Scientist. Can you give me one specific reference which supports the use of homeopathy in terms of Government policy on health?”. But answer came there none (well, there were words, but they made no sense). Then at the end of the session Harper said “homeopathic practitioners would argue that the way randomised clinical trials are set up they do not lend themselves necessarily to the evaluation and demonstration of efficacy of homeopathic remedies, so to go down the track of having more randomised clinical trials, for the time being at least, does not seem to be a sensible way forward.” Earlier, Kent Woods (CEO of the MHRA) had said “the underlying theory does not really give rise to many testable hypotheses”. These two eminent people seemed to have been fooled by the limp excuses offered by homeopaths. The hypotheses are testable and homeopathy, because it involves pills, is particularly well suited to being tested by proper RCTs (they have been, and when done properly, they fail). If you want to know how to do it, all you have to do is read Goldacre in the Guardian [16]. It really isn’t vert complicated. “Imagine going to an NHS hospital for treatment and being sent away with nothing but a bottle of water and some vague promises.” “And no, it’s not a fruitcake fantasy. This is homeopathy and the NHS currently spends around £10million on it.” That was written by health journalist Jane Symons, in The Sun [17]. A Murdoch tabloid has produced a better account of homeopathy than anything that could be managed by the chief scientific advisor to the Department of Health. And it isn’t often that one can say that. These examples serve to show that the medical establishment is slowly being dragged, from the bottom up, into realising that matters of truth and falsehood are more important than their knighthoods. It is all very heartening, both for medicine and for democracy itself. David Colquhoun. Declaration of interests. I was A.J. Clark chair of pharmacology at UCL, 1985 – 2004. 1. Aronson, JK BMJ 2009;339:b5415 2. Clark, A,J, (1938) Patent Medicines FACT series 14, London. See also Patent medicines in 1938 and now https://www.dcscience.net/?p=257 3. David Clark “Alfred Joseph Clark, A Memoir” (C. & J. Clark Ltd 1985 ISBN 0-9510401-0-3) 4. Lewis, A. (2007) The Gentle Art of Homeopathic Killing 5. A.J. Clark (1927) The historical aspect of quackery, BMJ October 1st 1927 6. Chrastina, D (2007) Quantum theory isn’t that weak, (response to Lionel Milgrom). 7 Goldacre, B. (2008) Bad Science. HarperCollins 8. Skills for Health web site 9. A very bad report: gamma minus for the vice-chancellor 10. A Patients’ Guide to Magic Medicine, and also in the Financial Times. 12. NICE fiasco, part 2. Rawlins should withdraw guidance and start again 13. BBC news 1 December 2009 Prince Charles: ‘Herbal medicine must be regulated’. 14. Oliver Wendell Holmes (1842) Homeopathy and Its Kindred Delusions. 15. House of Commons Science and technology committee. Evidence check: homeopathy. Videos and transcripts available at http://www.viewista.com/s/fywlp2/ez/1 16. Goldacre, B. A Kind of Magic Guardian 16 November 2007. 17. Homeopathy is resources drain says |

Follow-up

There is a good account of the third SCITECH session by clinical science consultant, Majikthyse, at The Three Amigos.

16 December 2009.. Recorded an interview for BBC Radio 5 Live. It was supposed to go out early on 17th.

17 December 2009. The editorial is mentioned in Editor’s Choice, by deputy editor Tony Delamothe. I love his way of putting the problem "too many at the top of British medicine seem frozen in the headlights of the complementary medicine bandwagon". He sounds remarkably kind given that I was awarded (by the editor, Fiona Godlee, no less) a sort of booby prize at the BMJ party for having generated a record number of emails during the editing of a single editorial (was it really 24?). Hey ho.

17 December 2009. More information on very direct political meddling by the Prince of Wales in today’s Guardian, and in Press Association report.

17 December 2009. Daily Telegraph reports on the editorial, under the heading “ ‘Nonsense’ alternative medicines should not be regulated“. Not a bad account for a non-health journalist.

17 December 2009. Good coverage in the excellent US blog, Neurologica, by the superb Steven Novella.’ “Intrepid, Ragged Band of Bloggers” take on CAM‘ provides a chance to compare and contrast the problems in the UK and the USA.’

18 December 2009. Article in The Times by former special advisor, Paul Richards. “The influence of Prince Charles the lobbyist is out of hand. Our deference stops us asking questions.”

“A good starting point might be publication of all correspondence over the past 30 years. Then we will know the extent, and influence, of Prince Charles the lobbyist.”

Comments in the BMJ Quite a lot of comments had appeared by January 8th, though sadly they were mostly from the usual suspects who appear every time one suggests evidence matters. A reply was called for, so I sent this (the version below has links).

After a long delay, this response eventually appeared in the BMJ on January 15 2010.

It’s good to see so many responses, though somewhat alarming to see that several of them seem to expect an editorial to provide a complete review of the literature. I ‘ll be happy to provide references for any assertion that I made.

I also find it a bit odd that some people think that an editorial is not the place to express an opinion robustly. That view seems to me to be a manifestation of the very sort of political correctness that I was deploring. It’s a bit like the case when the then health minister, Lord Hunt, referred to psychic surgery as a “profession” when he should have called it a fraudulent conjuring trick. Anything I write is very mild compared with what Thomas Wakley wrote in the Lancet, a journal which he founded around the time UCL came into existence. For example (I quote)

“[We deplore the] “state of society which allows various sets of mercenary, goose-brained monopolists and charlatans to usurp the highest privileges…. This is the canker-worm which eats into the heart of the medical body.” Wakley, T. The Lancet 1838-9, 1

I don’t think it is worth replying to people who cite Jacques Benveniste or Andrew Wakefield as authorities. Neither is it worth replying to people who raise the straw man argument about wicked pharmaceutical companies (about which I am on record as being as angry as anyone). But I would like to reply directly to some of the more coherent comments.

Sam Lewis and Robert Watson. [comment] Thank you for putting so succinctly what I was trying to say.

Peter Fisher [comment]. I have a lot of sympathy for Peter Fisher. He has attempted to do some good trials of homeopathy (they mostly had negative outcomes). He said he was "very angry" when the non-medical homeopaths were caught out recommending their sugar pills for malaria prevention (not that this as stopped such dangerous claims which are still commonplace). He agreed with me that there was not sufficient scientific basis for BSc degrees in homeopathy. I suppose that it isn’t really surprising that he continues to cherry pick the evidence. As clinical director of the Royal London Homeopathic Hospital and Homeopathic physician to the Queen, just imagine the cognitive dissonance that would result if he were to admit publicly that is all placebo after all. He has come close though. His (negative) trial for homeopathic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis included the words "It seems more important to define if homeopathists can genuinely control patients’ symptoms and less relevant to have concerns about whether this is due to a ‘genuine’ effect or to influencing the placebo response” [2]. [download

the paper]. When it comes to malaria, it matters a lot.

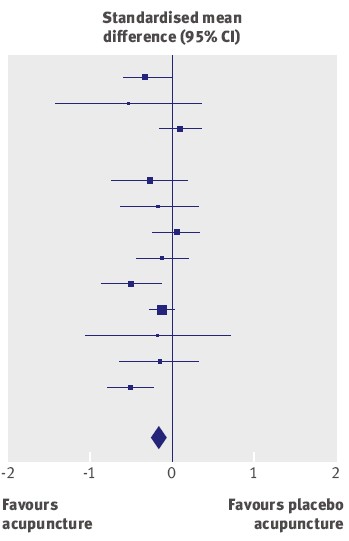

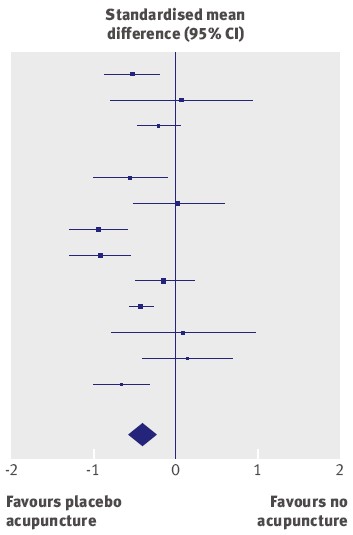

Adrian White [comment] seems to be cross because I cited my own blog. I did that simply because if he follows the links there he will find the evidence. In the case of acupuncture it has been shown time after time that "real" acupuncture does not differ perceptibly from sham. That is true whether the sham consists of retractable needles or real needles in the "wrong" places. A non-blind comparison between acupuncture and no acupuncture usually shows some advantage for the former but it is, on average, too small to be of much clinical significance [3]. I agree that there is no way to be sure that this advantage is purely placebo effect but since it is small and transient it really doesn’t matter much. Nobody has put it more clearly than Barker Bausell in his book, Snake Oil Science [4]

White also seems to have great faith in peer review. I agree that in real science it is probably the best system we have. But in alternative medicine journals the "peers" are usually other true believers in whatever hocus pocus is being promoted and peer reveiw breaks down altogether.

R. M. Pittilo [comment] I’m glad that Professor Pittilo has replied in person because I did single out his report for particular criticism. I agree that his report said that NHS funding should be available to CAM only where there is evidence of efficacy. That was not my criticism. My point was that in his report, the evidence for efficacy was assessed by representatives of Herbal Medicine, Chinese Medicine and Acupuncture (four from each). Every one of them would have been out of work if they had found their subjects were nonsense and that, no doubt, explains why the assessment was so bad. To be fair, they did admit that the evidence was not all that it might be and recommended (as always) more research I’d like to ask Professor Pittilo how much money should be spent on more research in the light of the fact that over a billion dollars has been spent in the USA on CAM research without producing a single useful treatment. Pittilo says "My own view is that both statutory regulation and the quest for evidence should proceed together" but he seems to neglect the possibility that the quest for evidence might fail. Experience in the USA suggests that is exactly what has, to a large extent, already happened.

I also find it quite absurd that the Pittilo report should recommend, despite a half-hearted admission that the evidence is poor, that entry to these subjects should be via BSc Honours degrees. In any case he is already thwarted in that ambition because universities are closing down degrees in these subjects having realised that the time to run a degree is after, not before, you have some evidence that the subject is not nonsense. I hope that in due course Professor Pittilo may take the same action about the courses in things like homeopathy that are run by the university of which he is vice-chancellor. That could only enhance the academic reputation of Robert Gordon’s University.

George Lewith [comment] You must be aware that the proposed regulatory body, the Health Professions Council, has already broken its own rules about "evidence-based practice" by agreeing to take on, if asked, practitioners of Herbal Medicine, Chinese Medicine and Acupuncture. They have (shamefully) excluded the idea that claims of efficacy would be regulated. In other word they propose to provide exactly the sort of pseudo-regulation which would endanger patients They are accustomed to the idea that regulation is to do only with censoring practitioners who are caught in bed with patients. However meritorious that may be, it is not the main problem with pseudo-medicine, an area in which they have no experience. I’m equally surprised that Lewith should recommend that Chinese evaluation of Traditional Chinese medicine should be included in meta-analyses, in view of the well-known fact that 99% of evaluations from China are positive: “No trial published in China or Russia/USSR found a test treatment to be ineffective” [5]. He must surely realise that medicine in China is a branch of politics. In fact the whole resurgence in Chinese medicine and acupuncture in post-war times has less to do with ancient traditions than with Chinese nationalism, in particular the wish of Mao Tse-Tung to provide the appearance of health care for the masses (though it is reported that he himself preferred Western Medicine).

1. Lord Hunt thinks “psychic surgery” is a “profession”. https://www.dcscience.net/?p=258

2. Fisher, P. Scott, DL. 2001 Rheumatology 40, 1052 – 1055. [pdf file]

3. Madsen et al, BMJ 2009;338:a3115 [pdf file]

4. R, Barker Bausell, Snake Oil Science, Oxford University Press, 2007

5. Vickers, Niraj, Goyal, Harland and Rees (1998, Controlled Clinical Trials, 19, 159-166) “Do Certain Countries Produce Only Positive Results? A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials”. [pdf file]

15 January 2010. During the SciTech hearings, Kent Woods (CEO of the MHRA) made a very feeble attempt to defend the MHRA’s decision to allow misleading labelling of homeopathic products. Now they have published their justification for this claim. It is truly pathetic, as explained by Martin at LayScience: New Evidence Reveals the MHRA’s Farcical Approach to Homeopathy. This mis-labelling cause a great outcry in 2006, as documented in The MHRA breaks its founding principle: it is an intellectual disgrace, and Learned Societies speak out against CAM, and the MHRA.

22 January 2010 Very glad to see that the minister himself has chosen to respond in the BMJ to the editorial

|

Rt Hon. Mike O’Brien QC MP, Minister of State for Health Services I am glad that David Colquhoun was entertained by my appearance before the Health Select Committee on Homeopathy. But he is mistaken when he says, “you cannot start to think about a sensible form of regulation unless you first decide whether or not the thing you are trying to regulate is nonsense.” Regulation is about patient safety. Acupuncture, herbal and traditional Chinese medicine involve piercing the skin and/or the ingestion of potentially harmful substances and present a possible risk to patients. The Pittilo Report recommends statutory regulation and we have recently held a public consultation on whether this is a sensible way forward. Further research into the efficacy of therapies such as Homeopathy is unlikely to settle the debate, such is the controversy surrounding the subject. That is why the Department of Health’s policy towards complementary and alternative medicines is neutral. Whether I personally think Homeopathy is nonsense or not is besides the point. As a Minister, I do not decide the correct treatment for patients. Doctors do that. I do not propose on this occasion to interfere in the doctor-patient relationship. |

Here is my response to the minister

|

I am very glad that the minister himself has replied. I think he is wrong in two ways, one relatively trivial but one very important. First, he is wrong to refer to homeopathy as controversial. It is not. It is quite the daftest for the common forms of magic medicine and essentially no informed person believes a word of it. Of course, as minister, he is free to ignore scientific advice, just as the Home Secretary did recently. But he should admit that that is what he is doing, and not hide behind the (imagined) controversy. Second, and far more importantly, he is wrong, dangerously wrong, to say it I was mistaken to claim that “you cannot start to think about a sensible form of regulation unless you first decide whether or not the thing you are trying to regulate is nonsense". According to that view it would make sense to grant statutory regulation to voodoo and astrology. The Pittilo proposals would involve giving honours degrees in nonsense if one took the minister’s view that it doesn’t matter whether the subjects are nonsense or not. Surely he isn’t advocating that? The minister is also wrong to suppose that regulation, in the form proposed by Pittilo, would do anything to help patient safety. Indeed there is a good case to be made that it would endanger patients (not to mention endangering tigers and bears). The reason for that is that the main danger to patients arises from patients being given “remedies” that don’t work. The proposed regulatory body, the Health Professions Council, has already declared that it is not interested in whether the treatments work or not. That in itself endangers patients. In the case of Traditional Chinese Medicine, there is also a danger to patients from contaminated medicines. The HPC is not competent to deal with that either. It is the job of the MHRA and/or Trading Standards. There are much better methods of ensuring patient safety that those proposed by Pittilo. In order to see the harm that can result from statutory regulation, it is necessary only to look at the General Chiropractic Council. Attention was focussed on chiropractic when the British Chiropractic Association decided, foolishly, to sue Simon Singh for defamation. That led to close inspection of the strength of the evidence for their claims to benefit conditions like infant colic and asthma. The evidence turned out to be pathetic, and the result was that something like 600 complaints were made to the GCC about the making of false health claims (including two against practices run by the chair of the GCC himself). The processing of these complaints is still in progress, but what is absolutely clear is that the statutory regulatory body, the GCC, had done nothing to discourage these false claims. On the contrary it had perpetrated them itself. No doubt the HPC would be similarly engulfed in complaints if the Pittilo proposals went ahead. It is one thing to say that the government chooses to pay for things like homeopathy, despite it being known that they are only placebos, because some patients like them. It is quite another thing to endanger patient safety by advocating government endorsement in the form of statutory regulation, of treatments that don’t work. I would be very happy to meet the minister to discuss the problems involved in ensuring patient safety. He has seen herbalists and other with vested interests. He has been lobbied by the Prince of Wales. Perhaps it is time he listened to the views of scientists too. |

Both the minister’s response, and my reply, were reformatted to appear as letters in the print edition of the BMJ, as well as comments on the web..

Two weeks left to stop the Department of Health making a fool of itself. Email your response to tne Pittilo consultation to this email address HRDListening@dh.gsi.gov.uk

I’ve had permission to post a submission that has been sent to the Pittilo consultation. The whole document can be downloaded here. I have removed the name of the author. It is written by the person who has made some excellent contributions to this blog under the pseudonym "Allo V Psycho".

The document is a model of clarity, and it ends with constructive suggestions for forms of regulation that will, unlike the Pittilo proposals, really protect patients

Here is the summary. The full document explains each point in detail.

|

Executive Summary

Instead, safe regulation of alternative practitioners should be through:

|

The first two recommendations for effective regulation are much the same as mine, but the the third one is interesting. The problem with the Cancer Act (1939), and with the Unfair Trading regulations, is that they are applied very erratically. They are the responsibility of local Trading Standards offices, who have, as a rule, neither the expertise nor the time to enforce them effectively. A Health Advertising Standards Authority could perhaps take over the role of enforcing existing laws. But it should be an authority with teeth. It should have the ability to prosecute. The existing Advertising Standards Authority produces, on the whole, excellent judgements but it is quite ineffective because it can do very little.

A letter from an acupuncturist

I had a remarkable letter recently from someone who actually practises acupuncture. Here are some extracts.

|

“I very much enjoy reading your Improbable Science blog. It’s great to see good old-fashioned logic being applied incisively to the murk and spin that passes for government “thinking” these days.” “It’s interesting that the British Acupuncture Council are in favour of statutory regulation. The reason is, as you have pointed out, that this will confer a respectability on them, and will be used as a lever to try to get NHS funding for acupuncture. Indeed, the BAcC’s mission statement includes a line “To contribute to the development of healthcare policy both now and in the future”, which is a huge joke when they clearly haven’t got the remotest idea about the issues involved.” “Before anything is decided on statutory regulation, the British Acupuncture Council is trying to get a Royal Charter. If this is achieved, it will be seen as a significant boost to their respectability and, by implication, the validity of state-funded acupuncture. The argument will be that if Physios and O.T.s are Chartered and safe to work in the NHS, then why should Chartered Acupuncturists be treated differently? A postal vote of 2,700 BAcC members is under-way now and they are being urged to vote “yes”. The fact that the Privy Council are even considering it, is surprising when the BAcC does not even meet the requirement that the institution should have a minimum of 5000 members (http://www.privy-council.org.uk/output/Page45.asp). Chartered status is seen as a significant stepping-stone in strengthening their negotiating hand in the run-up to statutory regulation.” “Whatever the efficacy of acupuncture, I would hate to see scarce NHS resources spent on well-meaning, but frequently gormless acupuncturists when there’s no money for the increasing costs of medical technology or proven life-saving pharmaceuticals.” “The fact that universities are handing out a science degree in acupuncture is a testament to how devalued tertiary education has become since my day. An acupuncture degree cannot be called “scientific” in any normal sense of the term. The truth is that most acupuncturists have a poor understanding of the form of TCM taught in P.R.China, and hang on to a confused grasp of oriental concepts mixed in with a bit of New Age philosophy and trendy nutritional/life-coach advice that you see trotted out by journalists in the women’s weeklies. This casual eclectic approach is accompanied by a complete lack of intellectual rigour. My view is that acupuncturists might help people who have not been helped by NHS interventions, but, in my experience, it has very little to do with the application of a proven set of clinical principles (alternative or otherwise). Some patients experience remission of symptoms and I’m sure that is, in part, bound up with the psychosomatic effects of good listening, and non-judgemental kindness. In that respect, the woolly-minded thinking of most traditional acupuncturists doesn’t really matter, they’re relatively harmless and well-meaning, a bit like hair-dressers. But just because you trust your hairdresser, it doesn’t mean hairdressers deserve the Privy Council’s Royal Charter or that they need to be regulated by the government because their clients are somehow supposedly “vulnerable”.” |

Earlier postings on the Pittilo recommendations

A very bad report: gamma minus for the vice-chancellor https://www.dcscience.net/?p=235

Article in The Times (blame subeditor for the horrid title)

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/guest_contributors/article4628938.ece

Some follow up on The Times piece

https://www.dcscience.net/?p=251

The Health Professions Council breaks its own rules: the result is nonsense

https://www.dcscience.net/?p=1284

Chinese medicine -acupuncture gobbledygook revealed

https://www.dcscience.net/?p=1950

Consultation opens on the Pittilo report: help top stop the Department of Health making a fool of itself https://www.dcscience.net/?p=2007

Why degrees in Chinese medicine are a danger to patients https://www.dcscience.net/?p=2043

One month to stop the Department of Health endorsing quackery. The Pittilo questionnaire, https://www.dcscience.net/?p=2310

Follow-up

More boring politics, but it matters. The two main recommendations of this Pittilo report are that

- Practitioners of Acupuncture, Herbal Medicine, Traditional Chinese Medicine should be subject to statutory regulation by the Health Professions Council

- Entry to the register should normally be through a Bachelor degree with Honours

For the background on this appalling report, see earlier posts.

A very bad report: gamma minus for the vice-chancellor

The Times (blame subeditor for the horrid title), and some follow up on the Times piece

The Health Professions Council breaks its own rules: the result is nonsense

Chinese medicine -acupuncture gobbledygook revealed

Consultation opens on the Pittilo report: help stop the Department of Health making a fool of itself

Why degrees in Chinese medicine are a danger to patients

The Department of Health consultation shuts on November 2nd. If you haven’t responded yet, please do. It would be an enormous setback for reason and common sense if the government were to give a stamp of official approval to people who are often no more than snake-oil salesman.

Today I emailed my submission to the Pittilo consultation to the Department of Health, at HRDListening@dh.gsi.gov.uk

The submission

I sent the following documents, updated versions of those already posted earlier.

- Submission to the Department of Health, for the consultation on the Pittilo report [download pdf].

- What is taught in degrees in herbal and traditional Chinese medicine? [download pdf]

- $2.5B Spent, No Alternative Med Cures [download pdf]

- An example of dangerous (and probably illegal) claims that are routinely made by TCM practitioners [download pdf]f

I also completed their questionnaire, despite its deficiencies. In case it is any help to anyone, this is what I said:

The questionnaire

Q1: What evidence is there of harm to the public currently as a result of the activities of acupuncturists, herbalists and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners? What is its likelihood and severity?

Harm

No Harm

Unsure

Comment

The major source of harm is the cruel deception involved in making false claims of benefit to desperate patients. This applies to all three.

In the case of herbal and TCM there is danger from toxicity because herbal preparations are unstandardised so those that do contain an active ingredient are given in an unknown dose. This is irresponsible and dangerous (but would not be changed by the proposals for regulation).

In addition TCM suffers from recurrent problems of contamination with heavy metals, prescription drugs and so on. Again this would not be the business of the proposed form of regulation.

Q2: Would this harm be lessened by statutory regulation? If so, how?

Yes

No

Unsure

The proposed form of regulation would be no help at all. The HPC has already said that it is not concerned with whether or not the drug works, and, by implication, does not see itself as preventing false health claims (just as the GCC doesn’t do this). False claims are the responsibility of Trading Standards who are meant to enforce the Consumer Protection Unfair Trading Regulations (May 2008), though they do not at present enforce them very effectively. Also Advertisng Standards. The proposed regulation would not help, and could easily hinder public safety as shown by the fact that the GCC has itself been referred to the Advertisng Standards Authority.

The questions of toxicity and contamination are already the responsibility of Trading Standards and the MHRA. Regulation by the HPC would not help at all. The HPC is not competent to deal with such questions.

Q3: What do you envisage would be the benefit to the public, to practitioners and to businesses, associated with introducing statutory regulation?

Significant benefit

Some benefit

No benefit

Unsure

This question is badly formulated because the answer is different according to whether you are referring to the public, to practitioners or to businesses.

The public would be endangered by the form of regulation that is proposed, as is shown very clearly by the documents that I have submitted separately.

In the case of practitioners and businesses, there might be a small benefit, if the statutory regulation gave the impression that HM and TCM had government endorsement and must therefore be safe and effective.

There is also one way that the regulation could harm practitioners and businesses. If the HPC received a very large number of complaints about false health claims, just as the GCC has done recently, not only would it cost a large amount of money to process the claims, but the attendant bad publicity could harm practitioners. It is quite likely that this would occur since false claims to benefit sick people are rife in the areas of acupuncture, HM and TCM.

Q4: What do you envisage would be the regulatory burden and financial costs to the public, to practitioners, and to businesses, associated with introducing statutory regulation? Are these costs justified by the benefits and are they proportionate to the risks? If so, in what way?

Justified

Not Justified

Unsure

Certainly not justified. Given that I believe that the proposed form of regulation would endanger patients, no cost at all would be justified. But even if there were a marginal benefit, the cost would be quite unjustified. The number of practitioners involved is very large. It would involve a huge expansion of an existing quango, at a time when the government is trying to reduce the number of quangos. Furthermore, if the HPC were flooded with complaints about false health claims, as the GCC has been, the costs in legal fees could be enormous.

Q5: If herbal and TCM practitioners are subject to statutory regulation, should the right to prepare and commission unlicensed herbal medicines be restricted to statutorily regulated practitioners?

Yes

No

Unsure

I don’t think it would make much difference. The same (often false) ideas are shared by all HM people and that would continue to be the same with or without SR.

Q6: If herbal and TCM practitioners are not statutorily regulated, how (if at all) should unlicensed herbal medicines prepared or commissioned by these practitioners be regulated?

They could carry on as now, but the money that would have been spent on SR should instead be used to give the Office of Trading Standards and the MHRA the ability to exert closer scrutiny and to enforce more effectively laws that already exist. Present laws, if enforced, are quite enough to protect the public.

Q7: What would be the effect on public, practitioners and businesses if, in order to comply with the requirements of European medicines legislation, practitioners were unable to supply manufactured unlicensed herbal medicines commissioned from a third party?

Significant effect

Some effect

No effect

Unsure

European laws,especialliy in food area, are getting quite strict about the matters of efficacy. The proposed regulation, which ignores efficacy, could well be incompatible with European law, if not now, then soon. This would do no harm to legitimate business though it might affect adversely businesses which make false claims (and there are rather a lot of the latter).

Q8: How might the risk of harm to the public be reduced other than by orthodox statutory regulation? For example by voluntary self-regulation underpinned by consumer protection legislation and by greater public awareness, by accreditation of voluntary registration bodies, or by a statutory or voluntary licensing regime?

Voluntary self-regulation

Accreditation of voluntary bodies

Statutory or voluntary licensing

Unsure

I disagree with the premise, for reasons given in detail in separate documents. I believe that ‘orthodox statutory regulation’, if that means the Pittilo proposals, would increase, not decrease, the risk to the public. Strengthening the powers of Trading Standards, the MHRA and such consumer protection legislation would be far more effective in reducing risk to the public than the HPC could ever be. Greater public awareness of the weakness of the evidence for the efficacy of these treatments would obviously help too, but can’t do the job on its own.

Q10: What would you envisage would be the benefits to the public, to practitioners, and to businesses, for the alternatives to statutory regulation outlined at Question 8?

It depends on which alternative you are referring to. The major benefit of enforcement of existing laws by Trading Standards and/or the MHRA would be (a) to protect the public from risk, (b) to protect the public from health fraud and (c) almost certainly lower cost to the tax payer.

Q11: If you feel that not all three practitioner groups justify statutory regulation, which group(s) does/do not and please give your reasons why/why not?

Acupuncture

Herbal Medicine

TCM

Unsure

None of them. The differences are marginal. In the case of acupuncture there has been far more good research than for HM or TCM. But the result of that research is to show that in most cases the effects are likely to be no more than those expected of a rather theatrical placebo. Furthermore the extent to which acupuncture has a bigger effect than no-acupuncture in a NON-BLIND comparison, is usually too small and transient to offer any clinical advantage (so it doesn’t really matter whether the effect is placebo or not, it is too small to be useful).

In the case of HM, and even more of TCM, there is simply not enough research to give much idea of their usefulness, with a small handful of exceptions.

This leads to a conclusion that DH seems to have ignored in the past. It makes absolutely no sense to talk about “properly trained practitioners” without first deciding whether the treatments work or not. There can be no such thing as “proper training” in a discipline that offers no benefit over placebo. It is a major fault of the Pittilo recommendations that they (a) ignore this basic principle and (b) are very over-optimistic about the state of the evidence.

Q12: Would it be helpful to the public for these practitioners to be regulated in a way which differentiates them from the regulatory regime for mainstream professions publicly perceived as having an evidence base of clinical effectiveness? If so, why? If not, why not?

Yes

No

Unsure

It might indeed be useful if regulation pointed out the very thin evidence base for HM and TCM but it would look rather silly. The public would say how can it be that the DH is granting statutory regulation to things that don’t work?

Q13: Given the Government’s commitment to reducing the overall burden of unnecessary statutory regulation, can you suggest which areas of healthcare practice present sufficiently low risk so that they could be regulated in a different, less burdensome way or de-regulated, if a decision is made to statutorily regulate acupuncturists, herbalists and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners?

Yes

No

Unsure

As stated above, the.only form of regulation that is needed, and the only form that would protect the public, is through consumer protection regulations, most of which already exist (though they are enforced in a very inconsistent way). Most statutory regulation is objectionable, not on libertarian grounds, but because it doesn’t achieve the desired ends (and is expensive). In this case of folk medicine, like HM and TCM, the effect would be exactly the opposite of that desired as shown in separate documents that I have submitted to the consultation.

Q14: If there were to be statutory regulation, should the Health Professions Council (HPC) regulate all three professions? If not, which one(s) should the HPC not regulate?

Yes

No

Unsure

The HPC should regulate none of them. It has never before regulated any form of alternative medicine and it is ill-equipped to do so. Its statement that it doesn’t matter that there is very little evidence that the treatments work poses a danger to patients (as well as being contrary to its own rules).

Q15: If there were to be statutory regulation, should the Health Professions Council or the General Pharmaceutical Council/Pharmaceutical Society of Northern Ireland regulate herbal medicine and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners?

HPC

GPC/PSNI

Unsure

Neither. The GPC is unlikely to care about whether the treatments work any more than the RPSGB did, or the GCC does now. The problems would be exactly the same whichever body did it.

Q16: If neither, who should and why?

As I have said repeatedly, it should be left to Trading Standards, the MHRA and other consumer protection regulation.

Q17:

a) Should acupuncture be subject to a different form of regulation from that for herbalism and traditional Chinese medicine? If so, what?

Yes

No

Unsure

b) Can acupuncture be adequately regulated through local means, for example through Health and Safety legislation, Trading Standards legislation and Local Authority licensing?

Yes

No

Unsure

(a) No -all should be treated the same. Acupuncture is part of TCM

(b) Yes

Q18.

a) Should the titles acupuncturist, herbalist and [traditional] Chinese medicine practitioner be protected?

b) If your answer is no which ones do you consider should not be legally protected?

Yes

No

Unsure

No. It makes no sense to protect titles until such time as it has been shown that the practitioners can make a useful contribution to medicine (above placebo effect). That does not deny that placebos may be useful at times. but if that is all they are doing, the title should be ‘placebo practitioners’.

Q19: Should a new model of regulation be tested where it is the functions of acupuncture, herbal medicine and TCM that are protected, rather than the titles of acupuncturist, herbalist or Chinese medicine practitioner?

Yes

No

Unsure

No. This makes absolutely no sense when there is so little knowledge about what is meant by the ” functions of acupuncture, herbal medicine and TCM”.Insofar as they don’t work (better than placebo), there IS no function. Any attempt to define function when there is so little solid evidence (at least for HM and TCM) is doomed to failure.

Q20: If statutory professional self-regulation is progressed, with a model of protection of title, do you agree with the proposals for “grandparenting” set out in the Pittilo report?

Yes

No

Unsure

No. I believe the Pittilo report should be ignored entirely. The whole process needs to be thought out again in a more rational way.

Q22: Could practitioners demonstrate compliance with regulatory requirements and communicate effectively with regulators, the public and other healthcare professionals if they do not achieve the standard of English language competence normally required for UK registration? What additional costs would occur for both practitioners and regulatory authorities in this case?

Yes

No

Unsure

No. It is a serious problem, in TCM especially, that many High Street practitioners speak hardly any English at all. That adds severely to the already considerable risks. There would be no reliable way to convey what was expected of them. it would be absurd for the taxpayer to pay for them to learn English for the purposes of practising TCM (of course there might be the same case as for any other immigrant for teaching English on social grounds).

Q23: What would the impact be on the public, practitioners and businesses (financial and regulatory burden) if practitioners unable to achieve an English language IELTS score of 6.5 or above are unable to register in the UK?

Significant impact

Some impact

No impact

Unsure

The question is not relevant. The aim of regulation is to protect the public from risk (and it should be, but isn’t, an aim to protect them from health fraud). It is not the job of regulation to promote businesses

Q24: Are there any other matters you wish to draw to our attention?

I have submitted three documents via HRDListening@dh.gsi.gov.uk. The first of these puts the case against the form of regulation proposed by Pittilo, far more fluently than is possible in a questionnaire.

Another shows examples of what is actually taught in degrees in acupuncture, HM and TCM. They show very graphically the extent to which the Pittilo proposals would endanger the public, if they were to be implemented..

The Health Professions Council (HPC) is yet another regulatory quango.

The HPC’s strapline is

|

|

At present the HPC regulates; Arts therapists, biomedical scientists, chiropodists/podiatrists, clinical scientists, dietitians, occupational therapists, operating department practitioners, orthoptists, paramedics, physiotherapists, prosthetists/orthotists, radiographers and speech & language therapists.

These are thirteen very respectable jobs. With the possible exception of art therapists, nobody would doubt for a moment that they are scientific jobs, based on evidence. Dietitians, for example, are the real experts on nutrition (in contrast to “nutritional therapists” and the like, who are part of the alternative industry). That is just as well because the ten criteria for registration with the HPC say that aspirant groups must have

“Practise based on evidence of efficacy”

But then came the Pittilo report, about which I wrote a commentary in the Times, and here, A very bad report: gamma minus for the vice-chancellor, and here.

Both the Pittilo report, the HPC, and indeed the Department of Health itself (watch this space), seem quite unable to grasp the obvious fact that you cannot come up with any sensible form of regulation until after you have decided whether the ‘therapy’ works or whether it is so much nonsense.

In no sense can “the public be protected” by setting educational standards for nonsense. But this obvioua fact seems to be beyond the intellectual grasp of the quangoid box-ticking mentality.

That report recommended that the HPC should regulate also Medical Herbalists, Acupuncturists and Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners. Even more absurdly, it recommended degrees in these subjects, just at the moment that those universities who run them are beginning to realise that they are anti-scientific subjects and closing down degrees in them.

How could these three branches of the alternative medicine industry possibly be eligible to register with the HPC when one of the criteria for registration is that there must be “practise based on evidence of efficacy”?

Impossible, I hear you say. But if you said that, I fear you may have underestimated the capacity of the official mind for pure double-speak.

The HPC published a report on 11 September 2008, Regulation of Medical Herbalists, Acupuncturists and Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners.

The report says

1. Medical herbalists, acupuncturists and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners should be statutorily regulated in the public interest and for public safety reasons.

2. The Health Professions Council is appropriate as the regulator for these professions.

3. The accepted evidence of efficacy overall for these professions is limited, but regulation should proceed because it is in the public interest.

But the last conclusion contradicts directly the requirement for “practise based on evidence of efficacy”. I was curious about how this contradiction

could be resolved so I sent a list of questions. The full letter is here.

The letter was addressed to the president of the HPC, Anna van der Gaag, but with the customary discourtesy of such organisations, it was not answered by her but by Michael Guthrie, Head of Policy and Standards He said

“Our Council considered the report at its meeting in July 2008 and decided that the regulation of these groups was necessary on the grounds of public protection. The Council decided to make a recommendation to the Secretary of State for Health that these groups be regulated.

http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/100023FEcouncil_20080911_enclosure07.pdf “.

This, of course, doesn’t answer any of my questions. It does not explain how the public is protected by insisting on formal qualifications, if the qualifications

happen to teach mythical nonsense. Later the reply got into deeper water.

“I would additionally add that the new professions criteria are more focused on the process and structures of regulation, rather than the underlying rationale for regulation – the protection of members of the public. The Council considered the group’s report in light of a scoring against the criteria. The criteria on efficacy was one that was scored part met. As you have outlined in your email (and as discussed in the report itself) the evidence of efficacy (at least to western standards) is limited overall, particularly in the areas of herbal medicines and traditional Chinese medicine. However, the evidence base is growing and there was a recognition in the report that the individualised approach to practice in these areas did not lend themselves to traditional RCT research designs.”

Yes, based on process and structures (without engaging the brain it seems). Rather reminiscent of the great scandal in UK Social Services. It is right in one respect though.

The evidence base is indeed growing, But it is almost all negative evidence. Does the HPC not realise that? And what about “at least by Western standards”? Surely the HPC is not suggesting that UK health policy should be determined by the standards of evidence of Chinese herbalists? Actually it is doing exactly that since its assessment of evidence was based on the Pittilo report in which the evidence was assessed (very badly) by herbalists.

One despairs too about the statement that

“there was a recognition in the report that the individualised approach to practice in these areas did not lend themselves to traditional RCT research designs”

Yes of course the Pittilo report said that, because it was written by herbalists! Had the HPC bothered to read Ben Goldacre’s column in the Guardian they would have realised that there is no barrier at all to doing proper tests. It isn’t rocket science, though it seems that it is beyond the comprehension of the HPC.

So I followed the link to try again to find out why the HPC had reached the decision to breach its own rules. Page 10 of the HPC Council report says

3. The occupation must practise based on evidence of efficacy This criterion covers how a profession practises. The Council recognizes the centrality of evidence-based practice to modern health care and will assess applicant occupations for evidence that demonstrates that:

- Their practice is subject to research into its effectiveness. Suitable evidence would include publication in journals that are accepted as

learned by the health sciences and/or social care communities- There is an established scientific and measurable basis for measuring outcomes of their practice. This is a minimum—the Council welcomes

evidence of there being a scientific basis for other aspects of practice and the body of knowledge of an applicant occupation- It subscribes to the ethos of evidence-based practice, including being open to changing treatment strategies when the evidence is in favour

of doing so.

So that sounds fine. Except that research is rarely published in “journals that are accepted as learned by the health sciences”. And of course most of the good evidence is negative anyway. Nobody with the slightest knowledge of the literature could possibly think that these criteria are satisfied by Medical Herbalists, Acupuncturists and Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners.

So what does the HPC make of the evidence? Appendix 2 tells us. It goes through the criteria for HPS registration.

“Defined body of knowledge: There is a defined body of knowledge, although approaches to practice can vary within each area.”

There is no mention that the “body of knowledge” is, in many cases, nonsensical gobbledygook and, astonishingly this criterion was deemed to be “met”!.

This shows once again the sheer silliness of trying to apply a list of criteria without first judging whether the subject is based in reality,

Evidence of efficacy. There is limited widely accepted evidence of efficacy, although this could be partly explained by the nature of the professions in offering bespoke treatments to individual patients. This criterion is scored part met overall.

Sadly we are not told who deemed this criterion to be “part met”. But it does say that “This scoring has been undertaken based on the information outlined in the [Pittilo] report”. Since the assessment of evidence in that report was execrably bad (having been made by people who would lose their jobs if

they said anything negative). it is no wonder that the judgement is overoptimistic!

Did the HPC not notice the quality of the evidence presented in the Pittilo report? Apparently not. That is sheer incompetence.

Nevertheless the criterion was not “met”, so they can’t join HPC, right? Not at all. The Council simply decided to ignore its own rules.

On page 5 of the Council’s report we see this.

The Steering Group [Pittilo] argues that a lack of evidence of efficacy should not prevent regulation but that the professions should be encouraged and funded to strengthen the evidence base (p.11, p. 32, p.34).

This question can be a controversial area and the evidence base of these professions was the focus of some press attention following the report’s publication. An often raised argument against regulation in such circumstances is that it would give credibility in the public’s eyes to treatments that are not proven to be safe or efficacious.

This second point is dead right, but it is ignored. The Council then goes on to say

In terms of the HPC’s existing processes, a lack of ‘accepted’ evidence of efficacy is not a barrier to producing standards of proficiency or making decisions about fitness to practise cases.

This strikes me as ludicrous, incompetent, and at heart, dishonest.

There will be no sense in policy in this area until the question of efficacy is referred to NICE. Why didn’t the HPC recommend that? Why has it not been done?

One possible reason is that I discovered recently that, although there are two scientific advisers in the Department of Health,. both of them claim that it is “not their role” to give scientific advice in this area. So the questions get referred instead to the Prince of Wales Foundation. That is no way to run a ship.