Peter Lawrence

There can be no doubt that the situation for women has improved hugely since I started at UCL, 50 years ago. At that time women were not allowed in the senior common room. It’s improved even more since the 1930s (read about the attitude of the great statistician, Ronald Fisher, to Florence Nightinglale David).

Recently Williams & Ceci published data that suggest that young women no longer face barriers in job selection in the USA (though it will take 20 years before that feeds through to professor level). But no sooner than one was feeling optimistic, along comes Tim Hunt who caused a media storm by advocating male-only labs. I’ll say a bit about that case below.

First some very preliminary concrete proposals.

The job of emancipation is not yet completed. I’ve recently become a member of the Royal Society diversity committee, chaired by Uta Frith. That’s made me think more seriously about the evidence concerning the progress of women and of black and minority ethnic (BME) people in science, and what can be done about it. Here are some preliminary thoughts. They are my opinions, not those of the committee.

I suspect that much of the problem for women and BME results from over-competitiveness and perverse incentives that are imposed on researchers. That’s got progressively worse, and it affects men too. In fact it corrupts the entire scientific process.

|

One of the best writers on these topics is Peter Lawrence. He’s an eminent biologist who worked at the famous Lab for Molecular Biology in Cambridge, until he ‘retired’. Here are three things by him that everyone should read. |

|

The politics of publication (Nature, 2003) [pdf]

The mismeasurement of science (Current Biology, 2007) [pdf]

The heart of research is sick (Lab Times, 2011) [pdf]

From Lawrence (2003)

"Listen. All over the world scientists are fretting. It is night in London and Deborah Dormouse is unable to sleep. She can’t decide whether, after four weeks of anxious waiting, it would be counterproductive to call a Nature editor about her manuscript. In the sunlight in Sydney, Wayne Wombat is furious that his student’s article was rejected by Science and is taking revenge on similar work he is reviewing for Cell. In San Diego, Melissa Mariposa reads that her article submitted to Current Biology will be reconsidered, but only if it is cut in half. Against her better judgement, she steels herself to throw out some key data and oversimplify the conclusions— her postdoc needs this journal on his CV or he will lose a point in the Spanish league, and that job in Madrid will go instead to Mar Maradona."

and

"It is we older, well-established scientists who have to act to change things. We should make these points on committees for grants and jobs, and should not be so desperate to push our papers into the leading journals. We cannot expect younger scientists to endanger their future by making sacrifices for the common good, at least not before we do."

From Lawrence (2007)

“The struggle to survive in modern science, the open and public nature of that competition, and the advantages bestowed on those who are prepared to show off and to exploit others have acted against modest and gentle people of all kinds — yet there is no evidence, presumption or likelihood that less pushy people are less creative. As less aggressive people are predominantly women [14,15] it should be no surprise that, in spite of an increased proportion of women entering biomedical research as students, there has been little, if any, increase in the representation of women at the top [16]. Gentle people of both sexes vote with their feet and leave a profession that they, correctly, perceive to discriminate against them [17]. Not only do we lose many original researchers, I think science would flourish more in an understanding and empathetic workplace.”

From Lawrence (2011).

"There’s a reward system for building up a large group, if you can, and it doesn’t really matter how many of your group fail, as long as one or two succeed. You can build your career on their success".

Part of this pressure comes from university rankings. They are statistically-illiterate and serve no useful purpose, apart from making money for their publishers and providing vice-chancellors with an excuse to bullying staff in the interests of institutional willy-waving.

And part of the pressure arises from the money that comes with the REF. A recent survey gave rise to the comment

"Early career researchers overwhelmingly feel that the research excellence framework has created “a huge amount of pressure and anxiety, which impacts particularly on those at the bottom rung of the career ladder"

In fact the last REF was conducted quite sensibly (e.g. use of silly metrics was banned). The problem was that universities didn’t believe that the rules would be followed.

For example, academics in the Department of Medicine at Imperial College London were told (in 2007) they are expected to

“publish three papers per annum, at least one in a prestigious journal with an impact factor of at least five”.

And last year a 51-year-old academic with a good publication record was told that unless he raised £200,000 in grants in the next year, he’d be fired. There can be little doubt that this “performance management” contributed to his decision to commit suicide. And Imperial did nothing to remedy the policy after an internal investigation.

Several other universities have policies that are equally brutal. For example, Warwick, Queen Mary College London and Kings College London.

Crude financial targets for grant income should be condemned as defrauding the taxpayer (you are compelled to make your work as expensive as possible) As usual, women and BME suffer disproportionately from such bullying.

What can be done about this in practice?

I feel that some firm recommendations will be useful.

One thing that could be done is to make sure that all universities sign, and adhere to, the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA), and adhere to the Athena Swan charter

The Royal Society has already signed DORA, but, shockingly, only three universities in the UK have done so (Sussex, UCL and Manchester).

Another well-meaning initiative is The Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers. It’s written very much from the HR point of view and I’d argue that that’s part of the problem, not part of the solution.

For example it says

“3. Research managers should be required to participate in active performance management, including career development guidance”

That statement is meaningless without any definition of how performance management should be done. It’s quite clear that “performance management”, in the form of crude targets, was a large contributor to Stefan Grimm’s suicide.

The Concordat places great emphasis in training programmes, but ignores the fact that it’s doubtful whether diversity training works, and it may even have bad effects.

The Concordat is essentially meaningless in its present form.

My proposals

I propose that all fellowships and grants should be awarded only to universities who have signed DORA and Athena Swan.

I have little faith that signing DORA, or the Concordat, will have much effect on the shop floor, but they do set a standard, and eventually, as with changes in the law, improvements in behaviour are effected.

But, as a check, It should be announced at the start that fellows and employees paid by grants will be asked directly whether or not these agreements have been honoured in practice.

Crude financial targets are imposed at one in six universities. Those who do that should be excluded from getting fellowships or grants, on the grounds that the process gives bad value to the funders (and taxpayer) and that it endangers objectivity.

Some thoughts in the Hunt affair

It’s now 46 years since I and Brian Woledge managed to get UCL’s senior common room, the Housman room, opened to women. That was 1969, and since then, I don’t think that I’ve heard any public statement that was so openly sexist as Tim Hunt’s now notorious speech in Korea.

Listen to Hunt, Connie St Louis and Jenny Rohn on the Today programme (10 June, 2015).

On the Today Programme, Hunt himself said "What I said was quite accurately reported" and "I just wanted to be honest", so there’s no doubt that those are his views. He confirmed that the account that was first tweeted by Connie St Louis was accurate

Inevitably, there was a backlash from libertarians and conservatives. That was fuelled by a piece in today’s Observer, in which Hunt seems to regard himself as being victimised. My comment on the Observer piece sums up my views.

|

I was pretty shaken when I heard what Tim Hunt had said, all the more because I have recently become a member of the Royal Society’s diversity committee. When he talked about the incident on the Today programme on 10 June, it certainly didn’t sound like a joke to me. It seems that he carried on for more than 5 minutes in they same vein. Everyone appreciates Hunt’s scientific work, but the views that he expressed about women are from the dark ages. It seemed to me, and to Dorothy Bishop, and to many others, that with views like that. Hunt should not play any part in selection or policy matters. The Royal Society moved with admirable speed to do that. The views that were expressed are so totally incompatible with UCL’s values, so it was right that UCL too acted quickly. His job at UCL was an honorary one: he is retired and he was not deprived of his lab and his living, as some people suggested. Although the initial reaction, from men as well as from women, was predictably angry, it very soon turned to humour, with the flood of #distractinglysexy tweets. It would be a mistake to think that these actions were the work of PR people. They were thought to be just by everyone, female or male, who wants to improve diversity in science. The episode is sad and disappointing. But the right things were done quickly. Now Hunt can be left in peace to enjoy his retirement. |

Look at it this way. If you were a young woman, applying for a fellowship in competition with men. what would you think if Tim Hunt were on the selection panel?

After all this fuss, we need to laugh.

Here is a clip from the BBC News Quiz, in which actor, Rebecca Front, gives her take on the affair.

Follow-up

Some great videos soon followed Hunt’s comments. Try these.

Nobel Scientist Tim Hunt Sparks a #Distractinglysexy Campaign

(via Jennifer Raff)

This video has some clips from an earlier one, from Suzi Gage “Science it’s a girl thing”.

15 June 2015

An update on what happened from UCL. From my knowledge of what happened, this is not PR spin. It’s true.

16 June 2015

There is an interview with Tim Hunt in Lab Times that’s rather revealing. This interview was published in April 2014, more than a year before the Korean speech. Right up to the penultimate paragraph we agree on just about everything, from the virtue of small groups to the iniquity of impact factors. But then right at the end we read this.

|

In your opinion, why are women still under-represented in senior positions in academia and funding bodies? Hunt: I’m not sure there is really a problem, actually. People just look at the statistics. I dare, myself, think there is any discrimination, either for or against men or women. I think people are really good at selecting good scientists but I must admit the inequalities in the outcomes, especially at the higher end, are quite staggering. And I have no idea what the reasons are. One should start asking why women being under-represented in senior positions is such a big problem. Is this actually a bad thing? It is not immediately obvious for me… is this bad for women? Or bad for science? Or bad for society? I don’t know, it clearly upsets people a lot. |

This suggests to me that the outburst on 8th June reflected opinions that Hunt has had for a while.

There has been quite a lot of discussion of Hunt’s track record. These tweets suggest it may not be blameless.

@alokjha @david_colquhoun #anecdotealert I spoke to a friend who was appalled by Hunt when she saw him speak a decade ago for same reasons.

— Dr*T (@Dr_star_T) June 16, 2015

@david_colquhoun @alokjha Sorry I can't. Told in confidence at the weekend. She's still in science research and it's not worth it.

— Dr*T (@Dr_star_T) June 16, 2015

That's v interestting. It's been alleged tht nobody has grumbled. It seems thay have, but they daren't come forward https://t.co/AlUz0mAJbt

— David Colquhoun (@david_colquhoun) June 16, 2015

19 June 2015

Yesterday I was asked by the letters editor of the Times, Andrew Riley, to write a letter in response to a half-witted, anonymous, Times leading article. I dropped everything, and sent it. It was neither acknowledged nor published. Here it is [download pdf].

|

One of the few good outcomes of the sad affair of Tim Hunt is that it has brought to light the backwoodsmen who are eager to defend his actions, and to condemn UCL. The anonymous Times leader of 16 June was as good an example as any.

|

Some quotations from this letter were used by Tom Whipple in an article about Richard Dawkins surprising (to me) emergence as an unreconstructed backwoodsman.

18 June 2015

Adam Rutherford’s excellent Radio 4 programme, Inside Science, had an episode “Women Scientists on Sexism in Science". The last speaker was Uta Frith (who is chair of the Royal Society’s diversity committee). Her contribution started at about 23 min.

Listen to Uta Frith’s contribution. ![]()

" . . this over-competitiveness, and this incredible rush to publish fast, and publish in quantity rather than in quality, has been extremely detrimental for science, and it has been disproportionately bad, I think, for under-represented groups who don’t quite fit in to this over-competitive climate. So I am proposing something I like to call slow science . . . why is this necessary, to do this extreme measurement-driven, quantitative judgement of output, rather than looking at the actual quality"

That, I need hardly say, is music to my ears. Why not, for example, restrict the number of papers that an be submitted with fellowship applications to four (just as the REF did)?

21 June 2015

I’ve received a handful of letters, some worded in a quite extreme way, telling me I’m wrong. It’s no surprise that 100% of them are from men. Most are from more-or-less elderly men. A few are from senior men who run large groups. I have no way to tell whether their motive is a genuine wish to have freedom of speech at any price. Or whether their motives are less worthy: perhaps some of them are against anything that prevents postdocs working for 16 hours a day, for the glory of the boss. I just don’t know.

I’ve had far more letters saying that UCL did the right thing when it accepted Tim Hunt’s offer to resign from his non job at UCL. These letters are predominantly from young people, men as well as women. Almost all of them ask not to be identified in public. They are, unsurprisingly, scared to argue with the eight Nobel prizewinners who have deplored UCL’s action (without bothering to ascertain the facts). The fact that they are scared to speak out is hardly surprising. It’s part of the problem.

What you can do, if you don’t want to put your head above the public parapet. is simply to email the top people at UCL, in private. to express your support. All these email addresses are open to the public in UCL’s admirably open email directory.

Michael Arthur (provost): michael.arthur@ucl.ac.uk

David Price (vice-provost research): d.price@ucl.ac.uk

Geraint Rees (Dean of the Faculty of Life Sciences): g.rees@ucl.ac.uk

All these people have an excellent record on women in science, as illustrated by the response to Daily Mail’s appalling behaviour towards UCL astrophysicist, Hiranya Pereis.

26 June 2015

The sad matter of Tim Hunt is over, at last. The provost of UCL, Michael Arthur has now made a statement himself. Provost’s View: Women in Science is an excellent reiteration of UCL’s principles.

By way of celebration, here is the picture of the quad, taken on 23 March, 2003. It was the start of the second great march to try to stop the war in Iraq. I use it to introduce talks, as a reminder that there are more serious consequences of believing things that aren’t true than a handful of people taking sugar pills.

11 October 2015

In which I agree with Mary Collins

Long after this unpleasant row died down, it was brought back to life yesterday when I heard that Colin Blakemore had resigned as honorary president of the Association of British Science Writers (ABSW), on the grounds that that organisation had not been sufficiently hard on Connie St Louis, whose tweet initiated the whole affair. I’m not a member of the ABSW and I have never met St Louis, but I know Blakemore well and like him. Nevertheless it seems to me to be quite disproportionate for a famous elderly white man to take such dramatic headline-grabbing action because a young black women had exaggerated bits of her CV. Of course she shouldn’t have done that, but it everyone were punished so severely for "burnishing" their CV there would be a large number of people in trouble.

Blakemore’s own statement also suggested that her reporting was inaccurate (though it appears that he didn’t submitted a complaint to ABSW). As I have said above, I don’t think that this is true to any important extent. The gist of it was said was verified by others, and, most importantly, Hunt himself said "What I said was quite accurately reported" and "I just wanted to be honest". As far as I know, he hasn’t said anything since that has contradicted that view, which he gave straight after the event. The only change that I know of is that the words that were quoted turned out to have been followed by "Now, seriously", which can be interpreted as meaning that the sexist comments were intended as a joke. If it were not for earlier comments along the same lines, that might have been an excuse.

Yesterday, on twitter, I was asked by Mary Collins, Hunt’s wife, whether I thought he was misogynist. I said no and I don’t believe that it is. It’s true that I had used that word in a single tweet, long since deleted, and that was wrong. I suspect that I felt at the time that it sounded like a less harsh word than sexist, but it was the wrong word and I apologised for using it.

So do I believe that Tim Hunt is sexist? No I don’t. But his remarks both in Korea and earlier were undoubtedly sexist. Nevertheless, I don’t believe that, as a person, he suffers from ingrained sexism. He’s too nice for that. My interpretation is that (a) he’s so obsessive about his work that he has little time to think about political matters, and (b) he’s naive about the public image that he presents, and about how people will react to them. That’s a combination that I’ve seen before among some very eminent scientists.

In fact I find myself in almost complete agreement with Mary Collins, Hunt’s wife, when she said (I quote the Observer)

“And he is certainly not an old dinosaur. He just says silly things now and again.” “Collins clutches her head as Hunt talks. “It was an unbelievably stupid thing to say,” she says. “You can see why it could be taken as offensive if you didn’t know Tim. But really it was just part of his upbringing. He went to a single-sex school in the 1960s.”

Nevertheless, I think it’s unreasonable to think that comments such as those made in Korea (and earlier) would not have consequences, "naive" or not, "joke" or not, "upbringing" or not,

It’s really not hard to see why there were consequences. All you have to do is to imagine yourself as a woman, applying for a grant or fellowship, and realising that you’d be judged by Hunt. And if you think that the reaction was too harsh, imagine the same words being spoken with "blacks", or "Jews" substituted for "women". Of course I’m not suggesting for a moment that he’d have done this, but if anybody did, I doubt whether many people would have thought it was a good joke.

9 November 2015

An impressively detailed account of the Hunt affair has appeared. The gist can be inferred from the title: "Saving Tim Hunt

The campaign to exonerate Tim Hunt for his sexist remarks in Seoul is built on myths, misinformation, and spin". It was written by Dan Waddell (@danwaddell) and Paula Higgins (@justamusicprof). It is long and it’s impressively researched. it’s revealing to see the bits that Louise Mensch omitted from her quotations. I can’t disagree with its conclusion.

"In the end, the parable of Tim Hunt is indeed a simple one. He said something casually sexist, stupid and inappropriate which offended many of his audience. He then confirmed he said what he was reported to have said and apologised twice. The matter should have stopped there. Instead a concerted effort to save his name — which was not disgraced, nor his reputation as a scientist jeopardized — has rewritten history. Science is about truth. As this article has shown, we have seen very little of it from Hunt’s apologists — merely evasions, half-truths, distortions, errors and outright falsehoods.

"

8 April 2017

This late addition is to draw attention to a paper, wriiten by Edwin Boring in 1951, about the problems for the advancement of women in psychology. It’s remarkable reading and many of the roots of the problems have hardly changed today. (I chanced on the paper while looking for a paper that Boring wrote about P values in 1919.)

Here is a quotation from the conclusions.

“Here then is the Woman Problem as I see it. For the ICWP or anyone else to think that the problem.can be advanced toward solution by proving that professional women undergo more frustration and disappointment than professional men, and by calling then on the conscience of the profession to right a wrong, is to fail to see the problem clearly in all its psychosocial complexities. The problem turns on the mechanisms for prestige, and that prestige, which leads to honor and greatness and often to the large salaries, is not with any regularity proportional to professional merit or the social value of professional achievement. Nor is there any presumption that the possessor of prestige knows how to lead the good life. You may have to choose. Success is never whole, and, if you have it for this, you mayhave to give it up for that.”

[This an update of a 2006 post on my old blog]

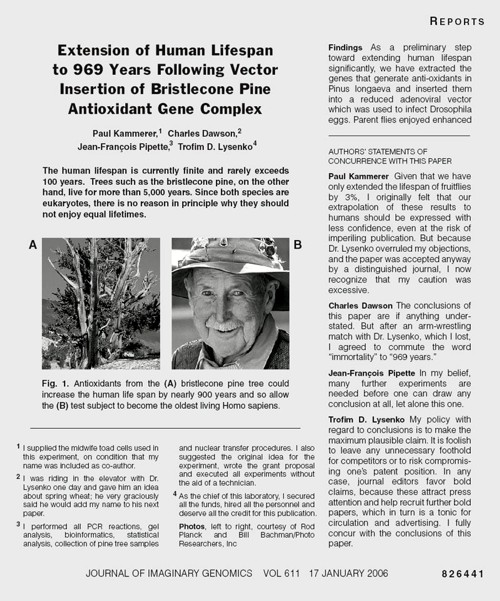

The New York Times (17 January 2006) published a beautiful spoof that illustrates only too clearly some of the bad practices that have developed in real science (as well as in quackery). It shows that competition, when taken to excess, leads to dishonesty.

More to the point, it shows that the public is well aware of the dishonesty that has resulted from the publish or perish culture, which has been inflicted on science by numbskull senior administrators (many of them scientists, or at least ex-scientists). Part of the blame must attach to "bibliometricians" who have armed administrators with simple-minded tools the usefulness is entirely unverified. Bibliometricians are truly the quacks of academia. They care little about evidence as long as they can sell the product.

The spoof also illustrates the folly of allowing the hegemony of a handful of glamour journals to hold scientists in thrall. This self-inflicted wound adds to the pressure to produce trendy novelties rather than solid long term work.

It also shows the only-too-frequent failure of peer review to detect problems.

The future lies on publication on the web, with post-publication peer review. It has been shown by sites like PubPeer that anonymous post-publication review can work very well indeed. This would be far cheaper, and a good deal better than the present extortion practised on universities by publishers. All it needs is for a few more eminent people like mathematician Tim Gowers to speak out (see Elsevier – my part in its downfall).

Recent Nobel-prizewinner Randy Schekman has helped with his recent declaration that "his lab will no longer send papers to Nature, Cell and Science as they distort scientific process"

The spoof is based on the fraudulent papers by Korean cloner, Woo Suk Hwang, which were published in Science, in 2005. As well as the original fraud, this sad episode exposed the practice of ‘guest authorship’, putting your name on a paper when you have done little or no work, and cannot vouch for the results. The last (‘senior’) author on the 2005 paper, was Gerald Schatten, Director of the Pittsburgh Development Center. It turns out that Schatten had not seen any of the original data and had contributed very little to the paper, beyond lobbying Scienceto accept it. A University of Pittsburgh panel declared Schatten guilty of “research misbehavior”, though he was, amazingly, exonerated of “research misconduct”. He still has his job. Click here for an interesting commentary.

The New York Times carried a mock editorial to introduce the spoof..

One Last Question: Who Did the Work? By NICHOLAS WADE In the wake of the two fraudulent articles on embryonic stem cells published in Science by the South Korean researcher Hwang Woo Suk, Donald Kennedy, the journal’s editor, said last week that he would consider adding new requirements that authors “detail their specific contributions to the research submitted,” and sign statements that they agree with the conclusions of their article. A statement of authors’ contributions has long been championed by Drummond Rennie, deputy editor of The Journal of the American Medical Association, Explicit statements about the conclusions could bring to light many reservations that individual authors would not otherwise think worth mentioning. The article shown [below] from a future issue of the Journal of imaginary Genomics, annotated in the manner required by Science‘s proposed reforms, has been released ahead of its embargo date. |

The old-fashioned typography makes it obvious that the spoof is intended to mock a paper in Science.

The problem with this spoof is its only too accurate description of what can happen at the worst end of science.

Something must be done if we are to justify the money we get and and we are to retain the confidence of the public

My suggestions are as follows

- Nature Science and Cell should become news magazines only. Their glamour value distorts science and encourages dishonesty

- All print journals are outdated. We need cheap publishing on the web, with open access and post-publication peer review. The old publishers would go the same way as the handloom weavers. Their time has past.

- Publish or perish has proved counterproductive. You’d get better science if you didn’t have any performance management at all. All that’s needed is peer review of grant applications.

- It’s better to have many small grants than fewer big ones. The ‘celebrity scientist’, running a huge group funded by many grants has not worked well. It’s led to poor mentoring and exploitation of junior scientists.

- There is a good case for limiting the number of original papers that an individual can publish per year, and/or total grant funding. Fewer but more complete papers would benefit everyone.

- Everyone should read, learn and inwardly digest Peter Lawrence’s The Mismeasurement of Science.

Follow-up

3 January 2014.

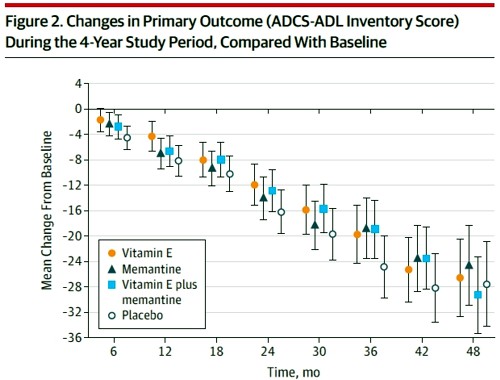

Yet another good example of hype was in the news. “Effect of Vitamin E and Memantine on Functional Decline in Alzheimer Disease“. It was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The study hit the newspapers on January 1st with headlines like Vitamin E may slow Alzheimer’s Disease (see the excellent analyis by Gary Schwitzer). The supplement industry was ecstatic. But the paper was behind a paywall. It’s unlikely that many of the tweeters (or journalists) had actually read it.

The trial was a well-designed randomised controlled trial that compared four treatments: placebo, vitamin E, memantine and Vitamin E + memantine.

Reading the paper gives a rather different impression from the press release. Look at the pre-specified primary outcome of the trial.

The primary outcome measure was

" . . the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study/Activities of Daily Living (ADCSADL) Inventory.12 The ADCS-ADL Inventory is designed to assess functional abilities to perform activities of daily living in Alzheimer patients with a broad range of dementia severity. The total score ranges from 0 to 78 with lower scores indicating worse function."

It looks as though any difference that might exist between the four treaments is trivial in size. In fact the mean difference between Vitamin E and placebos was only 3.15 (on a 78 point scale) with 95% confidence limits from 0.9 to 5.4. This gave a modest P = 0.03 (when properly corrected for multiple comparisons), a result that will impress only those people who regard P = 0.05 as a sort of magic number. Since the mean effect is so trivial in size that it doesn’t really matter if the effect is real anyway.

It is not mentioned in the coverage that none of the four secondary outcomes achieved even a modest P = 0.05 There was no detectable effect of Vitamin E on

- Mean annual rate of cognitive decline (Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale)

- Mean annual rate of cognitive decline (Mini-Mental State Examination)

- Mean annual rate of increased symptoms

- Mean annual rate of increased caregiver time,

The only graph that appeared to show much effect was The Dependence Scale. This scale

“assesses 6 levels of functional dependence. Time to event is the time to loss of 1 dependence level (increase in dependence). We used an interval-censored model assuming a Weibull distribution because the time of the event was known only at the end of a discrete interval of time (every 6 months).”

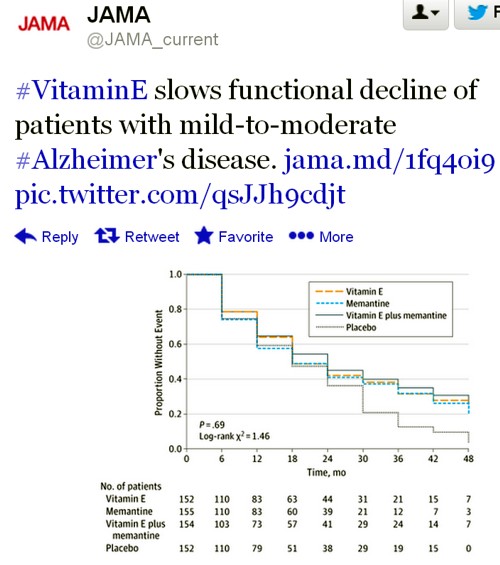

It’s presented as a survival (Kaplan-Meier) plot. And it is this somewhat obscure secondary outcome that was used by the Journal of the American Medical Assocciation for its publicity.

Note also that memantine + Vitamin E was indistinguishable from placebo. There are two ways to explain this: either Vitamin E has no effect, or memantine is an antagonist of Vitamin E. There are no data on the latter, but it’s certainly implausible.

The trial used a high dose of Vitamin E (2000 IU/day). No toxic effects of Vitamin E were reported, though a 2005 meta-analysis concluded that doses greater than 400 IU/d "may increase all-cause mortality and should be avoided".

In my opinion, the outcome of this trial should have been something like “Vitamin E has, at most, trivial effects on the progress of Alzheimer’s disease”.

Both the journal and the authors are guilty of disgraceful hype. This continual raising of false hopes does nothing to help patients. But it does damage the reputation of the journal and of the authors.

|

This paper constitutes yet another failure of altmetrics. (see more examples on this blog). Not surprisingly, given the title, It was retweeted widely, but utterly uncritically. Bad science was promoted. And JAMA must take much of the blame for publishing it and promoting it. |

|