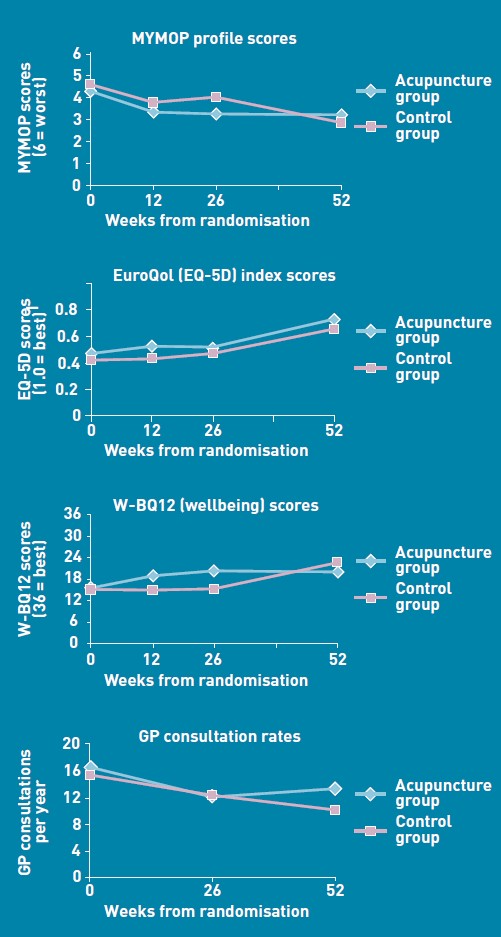

One wonders about the standards of peer review at the British Journal of General Practice. The June issue has a paper, "Acupuncture for ‘frequent attenders’ with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomised controlled trial (CACTUS study)". It has lots of numbers, but the result is very easy to see. Just look at their Figure.

There is no need to wade through all the statistics; it’s perfectly obvious at a glance that acupuncture has at best a tiny and erratic effect on any of the outcomes that were measured.

But this is not what the paper said. On the contrary, the conclusions of the paper said

|

Conclusion The addition of 12 sessions of five-element acupuncture to usual care resulted in improved health status and wellbeing that was sustained for 12 months. |

How on earth did the authors manage to reach a conclusion like that?

The first thing to note is that many of the authors are people who make their living largely from sticking needles in people, or advocating alternative medicine. The authors are Charlotte Paterson, Rod S Taylor, Peter Griffiths, Nicky Britten, Sue Rugg, Jackie Bridges, Bruce McCallum and Gerad Kite, on behalf of the CACTUS study team. The senior author, Gerad Kite MAc , is principal of the London Institute of Five-Element Acupuncture London. The first author, Charlotte Paterson, is a well known advocate of acupuncture. as is Nicky Britten.

The conflicts of interest are obvious, but nonetheless one should welcome a “randomised controlled trial” done by advocates of alternative medicine. In fact the results shown in the Figure are both interesting and useful. They show that acupuncture does not even produce any substantial placebo effect. It’s the authors’ conclusions that are bizarre and partisan. Peer review is indeed a broken process.

That’s really all that needs to be said, but for nerds, here are some more details.

How was the trial done?

The description "randomised" is fair enough, but there were no proper controls and the trial was not blinded. It was what has come to be called a "pragmatic" trial, which means a trial done without proper controls. They are, of course, much loved by alternative therapists because their therapies usually fail in proper trials. It’s much easier to get an (apparently) positive result if you omit the controls. But the fascinating thing about this study is that, despite the deficiencies in design, the result is essentially negative.

The authors themselves spell out the problems.

“Group allocation was known by trial researchers, practitioners, and patients”

So everybody (apart from the statistician) knew what treatment a patient was getting. This is an arrangement that is guaranteed to maximise bias and placebo effects.

"Patients were randomised on a 1:1 basis to receive 12 sessions of acupuncture starting immediately (acupuncture group) or starting in 6 months’ time (control group), with both groups continuing to receive usual care."

So it is impossible to compare acupuncture and control groups at 12 months, contrary to what’s stated in Conclusions.

"Twelve sessions, on average 60 minutes in length, were provided over a 6-month period at approximately weekly, then fortnightly and monthly intervals"

That sounds like a pretty expensive way of getting next to no effect.

"All aspects of treatment, including discussion and advice, were individualised as per normal five-element acupuncture practice. In this approach, the acupuncturist takes an in-depth account of the patient’s current symptoms and medical history, as well as general health and lifestyle issues. The patient’s condition is explained in terms of an imbalance in one of the five elements, which then causes an imbalance in the whole person. Based on this elemental diagnosis, appropriate points are used to rebalance this element and address not only the presenting conditions, but the person as a whole".

Does this mean that the patients were told a lot of mumbo jumbo about “five elements” (fire earth, metal, water, wood)? If so, anyone with any sense would probably have run a mile from the trial.

"Hypotheses directed at the effect of the needling component of acupuncture consultations require sham-acupuncture controls which while appropriate for formulaic needling for single well-defined conditions, have been shown to be problematic when dealing with multiple or complex conditions, because they interfere with the participative patient–therapist interaction on which the individualised treatment plan is developed. 37–39 Pragmatic trials, on the other hand, are appropriate for testing hypotheses that are directed at the effect of the complex intervention as a whole, while providing no information about the relative effect of different components."

Put simply that means: we don’t use sham acupuncture controls so we can’t distinguish an effect of the needles from placebo effects, or get-better-anyway effects.

"Strengths and limitations: The ‘black box’ study design precludes assigning the benefits of this complex intervention to any one component of the acupuncture consultations, such as the needling or the amount of time spent with a healthcare professional."

"This design was chosen because, without a promise of accessing the acupuncture treatment, major practical and ethical problems with recruitment and retention of participants were anticipated. This is because these patients have very poor self-reported health (Table 3), have not been helped by conventional treatment, and are particularly desperate for alternative treatment options.".

It’s interesting that the patients were “desperate for alternative treatment”. Again it seems that every opportunity has been given to maximise non-specific placebo, and get-well-anyway effects.

There is a lot of statistical analysis and, unsurprisingly, many of the differences don’t reach statistical significance. Some do (just) but that is really quite irrelevant. Even if some of the differences are real (not a result of random variability), a glance at the figures shows that their size is trivial.

My conclusions

(1) This paper, though designed to be susceptible to almost every form of bias, shows staggeringly small effects. It is the best evidence I’ve ever seen that not only are needles ineffective, but that placebo effects, if they are there at all, are trivial in size and have no useful benefit to the patient in this case..

(2) The fact that this paper was published with conclusions that appear to contradict directly what the data show, is as good an illustration as any I’ve seen that peer review is utterly ineffective as a method of guaranteeing quality. Of course the editor should have spotted this. It appears that quality control failed on all fronts.

Follow-up

In the first four days of this post, it got over 10,000 hits (almost 6,000 unique visitors).

Margaret McCartney has written about this too, in The British Journal of General Practice does acupuncture badly.

The Daily Mail exceeds itself in an article by Jenny Hope whch says “Millions of patients with ‘unexplained symptoms’ could benefit from acupuncture on the NHS, it is claimed”. I presume she didn’t read the paper.

The Daily Telegraph scarcely did better in Acupuncture has significant impact on mystery illnesses. The author if this, very sensibly, remains anonymous.

Many “medical information” sites churn out the press release without engaging the brain, but most of the other newspapers appear, very sensibly, to have ignored ther hyped up press release. Among the worst was Pulse, an online magazine for GPs. At least they’ve publish the comments that show their report was nonsense.

The Daily Mash has given this paper a well-deserved spoofing in Made-up medicine works on made-up illnesses.

“Professor Henry Brubaker, of the Institute for Studies, said: “To truly assess the efficacy of acupuncture a widespread double-blind test needs to be conducted over a series of years but to be honest it’s the equivalent of mapping the DNA of pixies or conducting a geological study of Narnia.” ”

There is no truth whatsoever in the rumour being spread on Twitter that I’m Professor Brubaker.

Euan Lawson, also known as Northern Doctor, has done another excellent job on the Paterson paper: BJGP and acupuncture – tabloid medical journalism. Most tellingly, he reproduces the press release from the editor of the BJGP, Professor Roger Jones DM, FRCP, FRCGP, FMedSci.

"Although there are countless reports of the benefits of acupuncture for a range of medical problems, there have been very few well-conducted, randomised controlled trials. Charlotte Paterson’s work considerably strengthens the evidence base for using acupuncture to help patients who are troubled by symptoms that we find difficult both to diagnose and to treat."

Oooh dear. The journal may have a new look, but it would be better if the editor read the papers before writing press releases. Tabloid journalism seems an appropriate description.

Andy Lewis at Quackometer, has written about this paper too, and put it into historical context. In Of the Imagination, as a Cause and as a Cure of Disorders of the Body. “In 1800, John Haygarth warned doctors how we may succumb to belief in illusory cures. Some modern doctors have still not learnt that lesson”. It’s sad that, in 2011, a medical journal should fall into a trap that was pointed out so clearly in 1800. He also points out the disgracefully inaccurate Press release issued by the Peninsula medical school.

Some tweets

Twitter info 426 clicks on http://bit.ly/mgIQ6e alone at 15.30 on 1 June (and that’s only the hits via twitter). By July 8th this had risen to 1,655 hits via Twitter, from 62 different countries,

@followthelemur Selina

MASSIVE peer review fail by the British Journal of General Practice http://bit.ly/mgIQ6e (via @david_colquhoun)

@david_colquhoun David Colquhoun

Appalling paper in Brit J Gen Practice: Acupuncturists show that acupuncture doesn’t work, but conclude the opposite http://bit.ly/mgIQ6e

Retweeted by gentley1300 and 36 others

@david_colquhoun David Colquhoun.

I deny the Twitter rumour that I’m Professor Henry Brubaker as in Daily Mash http://bit.ly/mt1xhX (just because of http://bit.ly/mgIQ6e )

@brunopichler Bruno Pichler

http://tinyurl.com/3hmvan4 Made-up medicine works on made-up illnesses (me thinks Henry Brubaker is actually @david_colquhoun)

@david_colquhoun David Colquhoun,

HEHE RT @brunopichler: http://tinyurl.com/3hmvan4 Made-up medicine works on made-up illnesses

@psweetman Pauline Sweetman

Read @david_colquhoun’s take on the recent ‘acupuncture effective for unexplained symptoms’ nonsense: bit.ly/mgIQ6e

@bodyinmind Body In Mind

RT @david_colquhoun: ‘Margaret McCartney (GP) also blogged acupuncture nonsense http://bit.ly/j6yP4j My take http://bit.ly/mgIQ6e’

@abritosa ABS

Br J Gen Practice mete a pata na poça: RT @david_colquhoun […] appalling acupuncture nonsense http://bit.ly/j6yP4j http://bit.ly/mgIQ6e

@jodiemadden Jodie Madden

amusing!RT @david_colquhoun: paper in Brit J Gen Practice shows that acupuncture doesn’t work,but conclude the opposite http://bit.ly/mgIQ6e

@kashfarooq Kash Farooq

Unbelievable: acupuncturists show that acupuncture doesn’t work, but conclude the opposite. http://j.mp/ilUALC by @david_colquhoun

@NeilOConnell Neil O’Connell

Gobsmacking spin RT @david_colquhoun: Acupuncturists show that acupuncture doesn’t work, but conclude the opposite http://bit.ly/mgIQ6e

@euan_lawson Euan Lawson (aka Northern Doctor)

Aye too right RT @david_colquhoun @iansample @BenGoldacre Guardian should cover dreadful acupuncture paper http://bit.ly/mgIQ6e

@noahWG Noah Gray

Acupuncturists show that acupuncture doesn’t work, but conclude the opposite, from @david_colquhoun: http://bit.ly/l9KHLv

8 June 2011 I drew the attention of the editor of BJGP to the many comments that have been made on this paper. He assured me that the matter would be discussed at a meeting of the editorial board of the journal. Tonight he sent me the result of this meeting.

|

Subject: BJGP Dear Prof Colquhoun We discussed your emails at yesterday’s meeting of the BJGP Editorial Board, attended by 12 Board members and the Deputy Editor The Board was unanimous in its support for the integrity of the Journal’s peer review process for the Paterson et al paper – which was accepted after revisions were made in response to two separate rounds of comments from two reviewers and myself – and could find no reason either to retract the paper or to release the reviewers’ comments Some Board members thought that the results were presented in an overly positive way; because the study raises questions about research methodology and the interpretation of data in pragmatic trials attempting to measure the effects of complex interventions, we will be commissioning a Debate and Analysis article on the topic. In the meantime we would encourage you to contribute to this debate throught the usual Journal channels Roger Jones Professor Roger Jones MA DM FRCP FRCGP FMedSci FHEA FRSA |

It is one thing to make a mistake, It is quite another thing to refuse to admit it. This reply seems to me to be quite disgraceful.

20 July 2011. The proper version of the story got wider publicity when Margaret McCartney wrote about it in the BMJ. The first rapid response to this article was a lengthy denial by the authors of the obvious conclusion to be drawn from the paper. They merely dig themselves deeper into a hole. The second response was much shorter (and more accurate).

|

Thank you Dr McCartney Richard Watson, General Practitioner The fact that none of the authors of the paper or the editor of BJGP have bothered to try and defend themselves speaks volumes. Like many people I glanced at the report before throwing it away with an incredulous guffaw. You bothered to look into it and refute it – in a real journal. That last comment shows part of the problem with them publishing, and promoting, such drivel. It makes you wonder whether anything they publish is any good, and that should be a worry for all GPs. |

30 July 2011. The British Journal of General Practice has published nine letters that object to this study. Some of them concentrate on problems with the methods. others point out what I believe to be the main point, there us essentially no effect there to be explained. In the public interest, I am posting the responses here [download pdf file]

Thers is also a response from the editor and from the authors. Both are unapologetic. It seems that the editor sees nothing wrong with the peer review process.

I don’t recall ever having come across such incompetence in a journal’s editorial process.

Here’s all he has to say.

|

The BJGP Editorial Board considered this correspondence recently. The Board endorsed the Journal’s peer review process and did not consider that there was a case for retraction of the paper or for releasing the peer reviews. The Board did, however, think that the results of the study were highlighted by the Journal in an overly-positive manner. However,many of the criticisms published above are addressed by the authors themselves in the full paper.

|

If you subscribe to the views of Paterson et al, you may want to buy a T-shirt that has a revised version of the periodic table.

5 August 2011. A meeting with the editor of BJGP

Yesterday I met a member of the editorial board of BJGP. We agreed that the data are fine and should not be retracted. It’s the conclusions that should be retracted. I was also told that the referees’ reports were "bland". In the circumstances that merely confirmed my feeling that the referees failed to do a good job.

Today I met the editor, Roger Jones, himself. He was clearly upset by my comment and I have now changed it to refer to the whole editorial process rather than to him personally. I was told, much to my surprise, that the referees were not acupuncturists but “statisticians”. That I find baffling. It soon became clear that my differences with Professor Jones turned on interpretations of statistics.

It’s true that there were a few comparisons that got below P = 0.05, but the smallest was P = 0.02. The warning signs are there in the Methods section: "all statistical tests were …. deemed to be statistically significant if P < 0.05". This is simply silly -perhaps they should have read Lectures on Biostatistics. Or for a more recent exposition, the XKCD cartoon in which it’s proved that green jelly beans are linked to acne (P = 0.05). They make lots of comparisons but make no allowance for this in the statistics. Figure 2 alone contains 15 different comparisons: it’s not surprising that a few come out "significant", even if you don’t take into account the likelihood of systematic (non-random) errors when comparing final values with baseline values.

Keen though I am on statistics, this is a case where I prefer the eyeball test. It’s so obvious from the Figure that there’s nothing worth talking about happening, it’s a waste of time and money to torture the numbers to get "significant" differences. You have to be a slavish believer in P values to treat a result like that as anything but mildly suggestive. A glance at the Figure shows the effects, if there are any at all, are trivial.

I still maintain that the results don’t come within a million miles of justifying the authors’ stated conclusion “The addition of 12 sessions of five-element acupuncture to usual care resulted in improved health status and wellbeing that was sustained for 12 months.” Therefore I still believe that a proper course would have been to issue a new and more accurate press release. A brief admission that the interpretation was “overly-positive”, in a journal that the public can’t see, simply isn’t enough.

I can’t understand either, why the editorial board did not insist on this being done. If they had done so, it would have been temporarily embarrassing, certainly, but people make mistakes, and it would have blown over. By not making a proper correction to the public, the episode has become a cause célèbre and the reputation oif the journal will suffer permanent harm. This paper is going to be cited for a long time, and not for the reasons the journal would wish.

Misinformation, like that sent to the press, has serious real-life consequences. You can be sure that the paper as it still stands, will be cited by every acupuncturist who’s trying to persuade the Department of Health that he’s a "qualified provider".

There was not much unanimity in the discussion up to this point, Things got better when we talked about what a GP should do when there are no effective options. Roger Jones seemed to think it was acceptable to refer them to an alternative practitioner if that patient wanted it. I maintained that it’s unethical to explain to a patient how medicine works in terms of pre-scientific myths.

I’d have love to have heard the "informed consent" during which "The patient’s condition is explained in terms of imbalance in the five elements which then causes an imbalance in the whole person". If anyone had tried to explain my conditions in terms of my imbalance in my Wood, Water, Fire, Earth and Metal. I’d think they were nuts. The last author. Gerad Kite, runs a private clinic that sells acupuncture for all manner of conditions. You can find his view of science on his web site. It’s condescending and insulting to talk to patients in these terms. It’s the ultimate sort of paternalism. And paternalism is something that’s supposed to be vanishing in medicine. I maintained that this was ethically unacceptable, and that led to a more amicable discussion about the possibility of more honest placebos.

It was good of the editor to meet me in the circumstances. I don’t cast doubt on the honesty of his opinions. I simply disagree with them, both at the statistical level and the ethical level.

30 March 2014

I only just noticed that one of the authors of the paper, Bruce McCallum (who worked as an acupuncturist at Kite’s clinic) appeared in a 2007 Channel 4 News piece. I was a report on the pressure to save money by stopping NHS funding for “unproven and disproved treatments”. McCallum said that scientific evidence was needed to show that acupuncture really worked. Clearly he failed, but to admit that would have affected his income.

Watch the video (McCallum appears near the end).

Hi David – just in case you’ve not seen, you’ve been nominated as ‘blog of the week’ in the current New Statesman.

Breath-taking stuff, David.

Like you. I am flabbergasted they can conclude anything like that from those graphs.

Is it too much to hope that your conclusions will get more publicity than theirs? (Ans: probably is too much, sadly)

And one does have to ask, as you do, what the journal editors were thinking of. Perhaps some well-directed egging in their direction will cause some of the currently-fashionable-in GP-world “self-reflection”.

Having said all that, though, I await with some dread the (inevitable?) credulous stories in the mainstream media based on the paper. Perhaps you should keep a running tab of them here?

David,

Your comments are entirely reasonable. To conclude that acupuncture is a “potentially effective intervention” is a ludicrous statement given the appalling methodology of this research.

The only tangible and objective outcome measure in the study was changed use of medication – which was negligible. All the other “measures” are qualitative, and involve the patient’s subjective impressions of their abilities (MYMOP scores etc). Subjective impressions of improvement are more susceptible to weekly coaching by therapists who are keen to get a positive outcome. For example Activities of Daily Living should really be assessed by a trained observer (nurse, paramedic etc), not as a self-completion exercise. Given this, it’s surprising that the differences bewteen the groups is so miniscule.

The problem is with this “black box” woffle is that it is hard to determine what exactly the intervention is.

1. Is it specifically needle insertion? If so, would random insertions of needles be equally as ineffective? We can’t say because other variables have not been isolated. But you certainly don’t need 60 minutes to insert a few needles randomly.

2. Is the intervention simply a change in routine for patients with chronic problems? The act of attending a clinic on a weekly basis is a positive and enabling step to engage with the problem, rather than being passive victims. A proper control would have had the control group attend for hourly “non-acupuncture” sessions to eliminate this variable.

3. Is the intervention really just sympathy? The psycho-social effects of having a “listening” clinician, (especially for hour-long sessions!) are well known and research shows that clinicians who spend more time talking and listening to patients are perceived to be more effective as doctors by patients. Patients are pleased if they feel that their “doctor really understands me”, even though the clinical treatment is no different to that prescribed by more taciturn colleagues. In which case you don’t need to stick needles in and call the intervention “acupuncture”.

The “control” failed to provide equivalent sham intervention – and therefore the researchers completely failed to eliminate a placebo effect. Publication should have stopped at this point with a proper peer review, but as the editor Roger Jones admitted recently to the Science & Technology Select Committee (PR23), there are other incentives to publish like “novelty” and “newsworthiness”. Perhaps that explained how this poor quality study was allowed to slip through.

thank you very much David as ever

I received my British Journal of General Practice today – as a signed up member wanting to know the latest in professional developments – and am dismayed at the conclusions of this study. Have written about it here.

I am afraid that many people will go and buy this intervention on the back of the headlines.

Are you drawing the editor’s attention to your blog ?

Thanks Margaret. It’s always good to get the approval of a real doctor.

I’ve written to the editor, and also to the new Chair of the RCGP, the excellent Clare Gerada. When I get replies, I may post a summary of them in the follow-up.

I haven’t seen it in the newspapers yet, but even if the Journal retracts the paper (as they should), the damage is already done.

I heard about the paper when a BBC Health journalist asked me to give an opinion about it. When they got my opinion, they decided not to cover it. Let’s hope the rest of the media are equally sensible,

For me this illustrates the huge amount of charity that alt.med. gets.

Plausibility, particularly, being one of the hugest of giftings.

-r.c.

Pulse (a weekly magazine for GPs) has followed The Daily Mail approach with “Acupuncture may bring pain reduction and boost ‘mental energy’ for patients who visit their GP frequently with medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS), researchers have said.” See http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=4129678

@sablackman

I’m afraid you are quite write. There are now dozens of “medical information” sites that look serious, but actually do little more than churn out press release. Pulse appears to have been taken in totally by the spin. The best solution is not to read them.

Here is the comment I have just left on Northern Doctor’s blog – apologies for the duplicate posting.

———–comment—————-

You and David Colquhoun and Margaret McCartney have highlighted the weaknesses in this study.

Problems in the assessment of the risks of bias in this sort of study are discussed in detail in a paper that the RCGP rejected as being of no interest to their audience, but the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine published (J R Soc Med. 2011 Apr;104(4):155-61).

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21502214

Exposing the evidence gap for complementary and alternative medicine to be integrated into science-based medicine.

Power M, Hopayian K.

Abstract (with added paragraph breaks):

When people who advocate integrating conventional science-based medicine with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) are confronted with the lack of evidence to support CAM they counter by calling for more research, diverting attention to the ‘package of care’ and its non-specific effects, and recommending unblinded ‘pragmatic trials’.

We explain why these responses cannot close the evidence gap, and focus on the risk of biased results from open (unblinded) pragmatic trials. These are clinical trials which compare a treatment with ‘usual care’ or no additional care. Their risk of bias has been overlooked because the components of outcome measurements have not been taken into account.

The components of an outcome measure are the specific effect of the intervention and non-specific effects such as true placebo effects, cognitive measurement biases, and other effects (which tend to cancel out when similar groups are compared).

Negative true placebo effects (‘frustrebo effects’) in the comparison group, and cognitive measurement biases in the comparison group and the experimental group make the non-specific effect look like a benefit for the intervention group. However, the clinical importance of these effects is often dismissed or ignored without justification.

The bottom line is that, for results from open pragmatic trials to be trusted, research is required to measure the clinical importance of true placebo effects, cognitive bias effects, and specific effects of treatments.”

[…] that mean it’s the kind of study that gives big placebo effects, it still barely worked, say […]

“Hypotheses directed at the effect of the needling component of acupuncture consultations require sham-acupuncture controls which while appropriate for formulaic needling for single well-defined conditions, have been shown to be problematic when dealing with multiple or complex conditions, because they interfere with the participative patient–therapist interaction on which the individualised treatment plan is developed.”

Mmm. High quality studies with sham controls have demonstrated a weak or non-existent placebo effect for a variety of specific medical conditions.

Now this poor quality study shows a weak effect which because of the nature of the trial cannot be identified with any particular component of the treatment. The trial should be repeated with two groups: one receiving the 5-element spiel together with needles; the other receiving the needles alone.

Then we would know how important the element-spiel element really is. Then a sham-controlled trial could be undertaken to confirm what is presently known – that traditional point acupuncture needling is no more effective than random or non-needling.

@Toots

Well, since there seems to be next to no effect of needles + placebo, the only way needles could work if the placebo effect were negative – a nocebo effect. That doesn’t seem very likely.

@David

As pointed out by twaza there is an inherent likelihood of a nocebo effect occurring in the non-treatment group which needs to be accounted for.

What really doesn’t impress me is the attempt by the authors to justify not using sham-controls by saying there is more going on than merely the use of needles. That being so, they ought to have set things up to elucidate the relative importance of the different components of what I believe to be a combined placebo-nocebo effect. The authors have not provided any data to show otherwise.

Great stuff David, but I have to pick you up onj one detail. You wrote:

“It was what has come to be called a “pragmatic” trial, which means a trial done without proper controls”

This is wrong. A pragmatic trial is a trial done in real-world conditions, to estimate the effect that a treatment will have if introduced into real messy clinical practice, where patient populations are heterogeneous, treatments sometimes don’t get delivered ideally and so on. The other end of the spectrum is an explanatory trial, where conditions are more tightly controlled: restricted homogeneous patient group, careful control of treatment delivery and adherence to protocol etc. How “pragmatic” a trial is has nothing to do with the quality of the controls.

Just noticed that the authors of this paper describe it as a pragmatic trial, so perhaps we can add misunderstanding of terminology to their other failings.

@christonabike

That isn’t my understanding. Under real world conditions there aren’t any controls. That’s why it is far harder than most people imagine to use experience from real life.

When I said testing in real world conditions, I meant using the patients and conditions that exist in real clinical practice. A pragmatic trial itself still makes a valid controlled comparison between drug and placebo, a new intervention and standard cre, or whatever.

This link gives a good description of what people in the trials business mean by pragmatic. Whether the acupuncturists mean the same thing I am not sure.

http://www.consort-statement.org/index.aspx?o=1435

I’m with christonabike on this one. Although I wasn’t directly involved with the study, I was around in Oxford when a large MRC funded trial looked at comparing spinal surgery with conservative care for chronic low back pain (it found no difference).

The authors decided to look at spinal surgery in general rather than attempting to control for different surgical approaches, techniques, metalwork used, post-operative regimes etc. (which vary so much from one hospital to another).

In other words, this was a pragmatic study attempting to reflect patient’s real life experiences of spinal surgery in its totality rather than a comparison between the vastly differing approaches to spinal surgery.

This is what I understand to be a pragmatic trial. Whether it had good controls or not (it did) is neither here nor there.

Was that the spine stabilisation trial?

Most big multi-site trials funded (formerly) by the MRC and these days by the NIHR HTA Programme are at the pragmatic end of the spectrum.

It would be a bit unfortunate if “pragmatic” is being used by some people to mean something different.

[…] in the June issue of the British Journal of General Practice. This was covered pretty well on DC’s Improbable Science blog. The chart is here on the right hand side of this […]

http://www.mrc.ac.uk/Newspublications/News/MRC001904

@christonabike

Thanks for the link to the CONSORT statement about pragmatic trials. I have to say I find it pretty obscure. It doesn’t really explain either what is meant by “pragmatic” or when such trials would be acceptable. As described there, the pragmatic trial barely differs from a proper RCT, apart form the fact that they can be non-blind and therefore potentially misleading.

The key word, I think, is causal. The proper RCT, it says, is designed to test causality, and it is an absolute essential for testing any treatment to know that the treatment is the cause of any effects that are seen. The CONSORT statement is (disgracefully) vague about whether or not you can make causal inferences from (its version of) pragmatic trials. Until causality has been established, there is no point in going on to anything else.

The CONSORT statement uses. with little comment, the distinction between “efficacy” and “effectiveness”. This strikes me as a rather dishonest distinction (perhaps why it is so popular in the alternative world). If a treatment has effectiveness, but not efficacy, then it isn’t the treatment that’s effective but something else.

Regardless of how CONSORT uses the word, the term pragmatic is usually used in the alternative world, as it is in the BJGP paper, to indicate a design that doesn’t enable you to tell whether the treatment caused the response. Such trials are worthless,

I wasn’t aware of the (ab)use of the term “pragmatic trial” in the alternative world. I’ll look out for it now and tackle it when I see it!

As for pragmatic trials as I understand (and do) them – they don’t differ from proper RCTs, they ARE proper RCTs, and yes, you absolutely can make causal inferences from them. That is what they are designed for. Most of the trials that actually make a difference to clinical practice are pragmatic trials. Maybe the CONSORT paper wasn’t the most useful link – here’s a better one, a bit old but from a couple of big cheeses

http://www.bmj.com/content/316/7127/285.full

Well if you can make causal inferences, why make the distinction at all?

But the references you sent (for which, many thanks) say that pragmatic trials may be non-blind and that means they can’t give reliable information about causality. The causality has to be established clearly first, before going on to trials that can’t test it. otherwise we end up being misled.

It is also the case that the word “pragmatic” is, in the BJGP paper, and in the alternative world in general, not interpreted in the way you say it should be.

@Dudeistan

Perhaps you should explain why you posted a link to the MRC back pain study. It’s relevance isn’t obvious to me

Obviously you’d want trials to be properly blinded but sometimes it just isn’t possible – and that tends to be particularly the case at the pragmatic end of the spectrum, where trials may be evaluating things like medical therapy versus surgery, or cognitive behavioural therapy, that are impossible to blind. I don’t think the implication is that it’s OK for pragmatic trials to be non-blinded, but rather that sometimes they have to be.

If the trial has to be unblinded you need to be extra careful in the design and execution to guard against introduction of bias; for example, using outcomes that can’t be influenced by knowledge of an individual’s treatment (like death) or making sure that the people assessing outcomes are blinded.

So I’m agreeing with you really – do a properly blinded trial if you can, but if you can’t, a non-blinded trial should (if done properly) be much better than no trial at all.

@christonabike I don’t think there is any serious disagreement between us on the principles involved and I agree that there are some things that can’t be blinded. But when that is the case you have to admit that you can’t be sure about causality. I don’t believe that it is possible to make up for deficiencies in the design of the experiment (inevitable deficiencies sometimes) simply by being “extra careful”. You can’t replace missing data by careful thought.

Perhaps the most difficult field is diet and health. It’s almost impossible to do an RCT and when you try the results are mostly negative. The HRT results shows that in the absence of randomisation you can get a wrong answer and do positive harm. My post on Diet and health. What can you believe? illustrates these problems quite well I think. The problem of causality really is central and often very hard to be sure about. The answer in such cases is not to make it up, but to say we don’t know,

In the alt med field, it’s a bit different of course, They are rather fond of unblinded trials because that;s the only way they can get an (apparently) positive result. The fascinating thing about the BJGP paper is that, despite designing the trial to give maximum possible bias, they still didn’t get a positive result.

@DC

I was giving an example of what I understand to be a typical pragmatic trial.

[…] that respect, the result resembles those in a recent paper in the British Journal of General Practice that showed acupuncture didn’t even produce any […]

The responses of the BrJGP Editor and (by implication) the Editorial Board are extraordinarily complacent.

I wonder if there is anyone on their board with enough integrity to resign in protest?

Here is an extract from the letter from Les Rose:

Surely the ethics committee who sanctioned this study in the first place should have made such an enquiry themselves.

Checking out the editorial board of the Brit J GP, I notice there is a Professor Liam Smeeth, Professor of Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, on there.

I’d love to know what a Professor of Epidemiology (and the Chair of the Exam Board for an M.Sc. in Epidemiology), would have made of the trial design, the stats and their presentation, and the inferences drawn by the authors and by the journal’s Editor.

@Dr_Aust

Thanks for pointing that out. I’ll follow it up. It would certainly be very worrying if the entire editorial board followed the unapologetic line of the editor.

It seems to me to be to such a serious case of misrepresentation that resignations are called for.

[…] – thanks BJGP). These well written, and comprehensive articles – such as the likes of David Colquhoun, Euan Lawson and Margaret Mccartney – suggest the tide is truly shifting away from the […]

Dr Aust making fatal mistake in assuming Professors on Editorial boards actually read the journal they edit

@Ronanthebarbarian

In general, one would not expect an editor to have read everything that appeared in his/her journal.

In this case a press release was issued, which quoted the editor himself. In the circumstances one might have expected that he’d read the paper.

Two months later, after the paper in question ignited a bonfire of indignation, one would certainly have expected that Jones would have read it, The lack of any apology suggests that one of three things is true. 1. He still has not read the paper. 2. he is not capable of understanding graphs. Or, and I’d guess most likely, he is one of those people who is incapable of admitting that he made a mistake.

@Ronanthebarbarian

Fair point under routine circumstances, but at the point where the paper has become a bit of a cause celebre, and the Editor is proposing issuing a statement in the journal saying:

“at a meeting of the Ed Board they (you) backed me unanimously’

– you might hope some of that editorial board would have got as far as reading the paper, and demanding to see the reviews.

Personally, were I on the board, I would want to know in detail just how such a catastrophic f*ck up occurred in ‘my’ peer review process. After all, I’m not sure being on the Ed Board of a journal that gets known for publishing laughable crap does my career much of a favour. And I would also want to know how the Editor himself had committed such an ‘Epic Fail’, given that he tells us he was personally involved in the editing ans spinning of the paper.

In your article you ask

‘Does this mean that the patients were told a lot of mumbo jumbo about “five elements” (fire earth, metal, water, wood)? If so, anyone with any sense would probably have run a mile from the trial.’

Sadly, I suspect that many of your fellow citizens, people who you rub shoulders with, on public transport and in the street, rather than run a mile are strangely drawn, uncritically, to the aura of snake oil. The criticisms that this article in the BJGP has rightly attracted are likely to be forgotten by the wider public (if they registered at all) when the next celebrity endorsement appears in the popular press.

And, it appears, not only the popular press. I see that the Edinburgh International Book Festival (August 17) will feature a memoir by Kristin Hersh.

http://www.edbookfest.co.uk/the-festival/whats-on/kristin-hersh

She states that

“My understanding of acupuncture was that it’s subtle. I’d no idea they could treat bipolar disorder with it. It’s mind blowing!”

And

After a lifetime on powerful prescription drugs that destroyed her liver and thyroid and made her thinking “robotic” she still can’t credit the transformation acupuncture has wrought in her physically and mentally. “I feel like I did when I was a child-I’ve never felt so clean or clear-thinking. The energy! Unbelievable!”

http://www.heraldscotland.com/arts-ents/book-features/kristin-hersh-muses-on-life-and-overcoming-bipolar-disorder-1.1114905

I fear that celebrity offerings like this have the potential to turn you into a blogging Sisyphus (the mythical character not the protein database).

@CrewsControl

Well, some do and some. I’ve met plenty of people with no scientific background at all who’d laugh at such nonsense, as well as plenty who’d like it. I have the impression that the first category is waning now, after 30 years of flourishing. Even the Daily Mail now sometimes prints sensible stuff.

In any case, the people I’m aiming at are not (primarily) the general public, but the Department of Health and vice-chancellors who should know better, and who have the power to do something about it.

In the particular example you cite, I’m worried that the Lewisham Ethics committee think that it’s ethical to allow that sort of “explanation” to be given to patients (I’ve written to them -watch this space).

I expect we’ll always have the High Street quacks (though they could decline back to the 1960s level). That’s fine (as long as they stay within the law -which most don’t).

People should be allowed their fantasies. My objection is to the corruption of real science, and the wasting of taxpayers’ money, on nonsense. I think there is some some success on that front.

[…] here too. There is now little doubt that it’s anything more than a theatrical, and not very effective, placebo. So this time I’ll concentrate on Western herbal […]

Fundamentalists in both camps (western and alternative) undermine the complexity of the EBM debate and this is no exception. If you are such a staunch protester of spin in this field, I am rather puzzled by your own spin here…this smacks of a hidden agenda and I do not feel it helps the debate.

The research was conducted with the aim of assessing the effectiveness of acupuncture for a specific group of patients in primary care (not a group I would choose to study if I was trying to bias the results towards the effectiveness of acupuncture by the way!).

If a study was undertaken to look at the efficacy of a drug routinely used in the treatment of parkinson’s (lets say) in the management of people with pituitary tumours, and the outcomes showed statistically insignificant benefits – would you blog: ‘researchers show parkinson’s drug does not work!’?

I can only imagine that if the results were more favourable you would also have highlighted the fact this study only looked at 80 patients and that this study was too small to be of any significance.

@KTenn

I’m not at all sure what point you are trying to make. I’m saying simply that the results in the Figure are incompatible with the conclusions drawn by the authors (and by the journal).

Do you agree with that, or disagree?

As I mention, other non-blind studies have shown a somewhat larger advantage for acupuncture (thou usually not large enough to be of clinical significance). That could easily, though not necessarily, be a placebo effect.

The most consistent finding is that there is no difference between sham acupuncture and real. and that certainly seems to show that the alleged ‘principles’ are sheer mumbo jumbo.

If the results had been for a statins, or for a Parkinson’s drug, my reaction would have been precisely the same. The emerging evidence of the ineffectiveness of SSRIs in mild/moderate depression is every bit as interesting as this paper. But it wasn’t denied by editors as in this case.

It’s true that 80 isn’t a huge number, but it should have been enough to reveal any substantial effect. If the results had looked positive, I’d regard that as suggesting that a bigger trial might be justified, just as with any other treatment. But they weren’t positive.

[…] failures in peer review. In June, the British Journal of General Practice published a paper, “Acupuncture for ‘frequent attenders’ with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomised c…“. It has lots of numbers, but the result is very easy to see. All you have to do is look at […]

[…] failures in peer review. In June, the British Journal of General Practice published a paper, “Acupuncture for ‘frequent attenders’ with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomised c…“. It has lots of numbers, but the result is very easy to see. All you have to do is look at […]

I’ll bet a quid that the anonymous author of the Telegraph piece was Anna Murphy.

“Over and above the relief of particular physical problems, what Kite gifts his patients is something they often weren’t aware they had lost: that ineffable sense of ‘me-ness’ that a child is born with but that many of us mislay along the way.”

The gals just love those needles, oh yes they do…

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/alternativemedicine/5055611/Acupuncture-Guy-of-the-needles.html

Damn; sorry David, hadn’t spotted that you already had the Telegraph link in my last comment. Kite. Great man… deep, great man, clearly!

The other (anonymous) Telegraph blurb quotes Charlotte Paterson as saying that in addition to being a safe and effective treatment five-elemement acupuncture could save the NHS money. Yet her study states that there was no decrease in attendance of patients at GPs’ surgeries and no reduction in their use of medications. Obviously, adding acupuncture to patients’ existing treatment can only add to NHS costs. Paterson says she plans a cost-effectiveness study. What a total waste of money that would be!

The fact that there was no change in patients’ existing use of their GPs and medications cannot be squared with the claim that patients showed “significantly improved” overall wellbeing, as quoted in The Telegraph – though one or two may have felt better in “spirit”.

Could it be that Paterson and colleagues have used their study (consciously or otherwise) to support a preferred “holistic” viewpoint: ancient Chinese five-element acupuncture, good for the soul/spirit, good for the body?

[…] findings on the news, on line and in glossy magazines. There are occasional news articles following unfavourable research findings and discussing controversial degree courses in acupuncture. So what’s acupuncture all about? […]

David, you said on May 31st that you had written to Clare Gerada on this subject. What was her response?

@Colin Forster

Very little I’m afraid. She’s been incredibly busy with trying to prevent the selling off of the NHS to the companies who are eager to cash in on Andrew Lansley’s proposals. She also regards the matter, quite rightly, as being the responsibility of the editor of BJGP.

It is certainly very disappointing that the editor has not seen fit to withdraw his press release. Neither have the authors backed off in any way. One of the authors, Nicky Britten, actually raised the matter again in the BMJ, as evidence of a witch hunt against CAM. This seems an odd reaction to it having been pointed out that the data were misinterpreted. It also shows that no amount of rational argument will persuade the true believer in alternative medicine.

[…] but no longer. Perhaps his views are too weird even for their Third Gap section (the folks who so misrepresented their results in a trial of acupuncture). Unsurprisingly, he was involved in the late Prince’s Foundation […]

[…] han estado en desacuerdo unas de otras. Podemos asumir ciertos fallos metodológicos, pero los errores de interpretación de resultados parece algo más forzado. Pero volviendo a los estudios sobre la falsa acupuntura, no parece fácil […]

[…] Spin is rife. Companies, and authors, want to talk up their results. University PR departments want to exaggerate benefits. Journal editors want sensational papers. Read the results, not the summary. This is universal (but particularly bad in alternative medicine). […]

[…] Or, there’s this rebuttal. […]

[…] An even more extreme example of spin occurred in the CACTUS trial of acupuncture for " ‘frequent attenders’ with medically unexplained symptoms” (Paterson et al., 2011). In this case, the results showed very little difference even between acupuncture and no-acupuncture groups, despite the lack of blinding and lack of proper controls. But by ignoring the problems of multiple comparisons the authors were able to pick out a few results that were statistically significant, though trivial in size. But despite this unusually negative outcome, the result was trumpeted as a success for acupuncture. Not only the authors, but also their university’s PR department and even the Journal editor issued highly misleading statements. This gave rise to a flood of letters to the British Journal of General Practice and much criticism on the internet. […]

Hello David and all,

I hope it is appropriate for me to post here in spite of my lack medical or statistical education.

I am certified as an acupuncturist, and was blown away by this and other articles on the site. Thanks for bringing this info to my attention! Somehow, I adopted the false impression that acupuncture was fairing moderately well for treatment of chronic pain…

I completely agree with what you wrote in “acupuncture is a theatrical placebo” (a statement which I tend to generally agree with, too):

“There is no point in discussing surrogate outcomes such as fMRI studies or endorphine release studies until such time as it has been shown that patients get a useful degree of relief. It is now clear that they don’t. “

Studies should be restricted to measuring alleviation of symptoms.

That being said, the fact that patients are “duped” into buying into a theatrical placebo (I hope I’m not misusing this term) is a good thing, because it helps cure them. The fact that the scientific community, in this case joined by acupuncture practitioners, buys into the fact that the act of needling is supposedly singularly responsible for any alleged alleviation of symptoms is not a good thing. This leads to needless fretting over issues of sterility in the studies, like the content of conversations between the needlers and the patients.

I can understand the tendency to focus on technical issues related to the treatment (point selection, needling methods etc.), but as you showed, there is no statistical significance to these variables. In my experience, every aspect of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) treatment is geared towards inducing a strong placebo effect. Studies in this field should motivated by the will to develop stronger placebo effects. It shouldn’t matter if a toothpick (or for that matter a ouija board) are used. In this case, treating placebo as a statistical obstacle clearly misses out on the main benefit of TCM for patients.

The human element in the tests should not be negated (apparently, this is rarely properly done) but made a central part of the study – perhaps like in a study of the effectiveness of psychotherapy.

Tomehr

@Tomehr

You are certainly very welcome to comment. I much prefer a dialogue, rather than simply lecturing people.

Also, your qualifications are irrelevant, It is what you say that matters, not what letters you have after your name.

I thought that your comment was very interesting. It is certainly very heartening that, although you are trained as an acupuncturist, you are willing to listen to evidence, and when the evidence contradicts your views, then you change your views. That is exactly how science works.

The only thing that I can’t agree with entirely is your view of the placebo effect. The study in this post is interesting because it shows essentially no placebo effect at all. Despite the fact that the comparison of acupuncture vs no-acupuncture was not blind, there is very little difference between the outcomes. That suggests that the perception that acupuncture works is a result of the get-better-anyway effect (regression to the mean) rather than a placebo effect.

The post on Acupuncture is a theatrical placebo cites work that suggest that this is a general phenomenon. Although some studies show a bigger difference between acupuncture vs no-acupuncture than in Paterson et al, the average difference is too small for it to be noticeable to the patient.

Thanks for the welcome and for the response.

I’m doing my best to resolve the conflict between my personal acquaintance with acupuncture and results of large scale studies, as they appear on your site.

I understand that this study is too susceptible to bias, and that this is not unusual practice in testing acupuncture. I can also understand how this could naturally be assumed to tilt results in favor of acupuncture’s ineffectiveness. However, the connection between the inaccuracy of this and other studies and the conflict of interest of the producers of the study is circumstantial.

You seem to be promoting the assumption that the more accurate studies in this field would be, the more conclusively they would disprove acupuncture’s presumed effectiveness. I think you may be partially relying on this assumption when advocating a cessation of study in this field. Don’t you think that a responsible conclusion must necessarily rely on higher quality studies produced by scientists?

Thanks,

Tomehr

@Tomehr

Yes, clearly it is sensible to place more reliance on trials that are larger and better-designed. There have been over 3000 trials now, and several of them are large and well-designed. They have failed to show any good evidence that acupuncture has a large enough effect to be of clinical significance. A regular drug that had been tested 3000 times with a similar record of failure would have been thrown out a long time ago. It seems to me that it would be a waste of money to pursue the field any further.

David,

Thank you for your responses. Your articles and this conversation have been very significant in altering my views of acupuncture. Despite the time and effort I’ve spent studying acupuncture and the natural personal affinity I’ve developed towards acupuncture’s theory and practice, I feel I have no choice but to agree with you. I don’t promise never to comment here with contrary opinions in the future, though.

All the best,

Tomehr

@tomehr

It’s good to hear that I, or rather the data, have changed your mind.

Please send opinions, contrary or otherwise, any time you like. It’s good to talk.

[…] In some cases, the abstract of a paper states that a discovery has been made when the data say the opposite. This sort of spin is common in the quack world. Yet referees and editors get taken in by the ruse (e.g see this study of acupuncture). […]

[…] Unfortunately for its advocates, it turned out that there is very little evidence that any of it works. This attention to evidence annoyed the Prince, and a letter was sent from Clarence House to Ernst’s boss, the vice-chancellor of the University of Exeter, Steve Smith. Shamefully, Smith didn’t tell the prince to mind his own business, but instead subjected Ernst to disciplinary proceedings. After a year of misery, Ernst was let off with a condescending warning letter, but he was forced to retire early in 2011 and the vice-chancellor was rewarded with a knighthood. His university has lost an honest scientist but continues to employ quacks. […]

[…] Perhaps the worst example of interference by the Prince of Wales, was his attempt to get an academic fired. Prof Edzard Ernst is the UK’s foremost expert on alternative medicine. He has examined with meticulous care the evidence for many sorts of alternative medicine.Unfortunately for its advocates, it turned out that there is very little evidence that any of it works. This attention to evidence annoyed the Prince, and a letter was sent from Clarence House to Ernst’s boss, the vice-chancellor of the University of Exeter, Steve Smith. Shamefully, Smith didn’t tell the prince to mind his ow business, but instead subjected Ernst to disciplinary proceedings, After subjecting him to a year of misery, he was let off with a condescending warning letter, but Ernst was forced to retire early. In 2011and the vice-chancellor was rewarded with a knighthood. His university has lost an honest scientist but continues to employ quacks. […]

[…] failures in peer review. In June, the British Journal of General Practice published a paper, “Acupuncture for ‘frequent attenders’ with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomised c…“. It has lots of numbers, but the result is very easy to see. All you have to do is look at […]